A Tale of Two Cities: Reconstructing the ‘Bajao Pungi, Hatao Lungi’ campaign in Bombay, and the Birth of the ‘Other’

Abstract

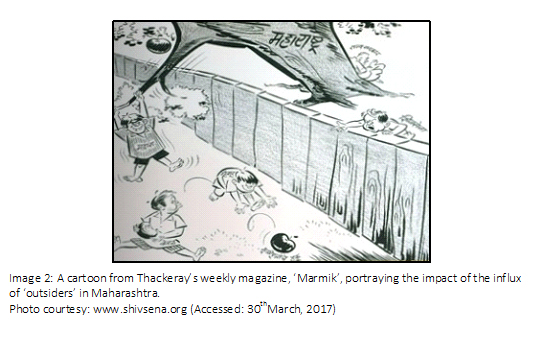

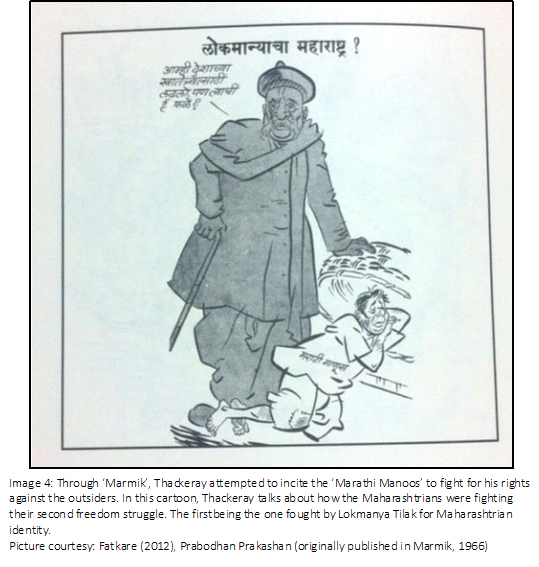

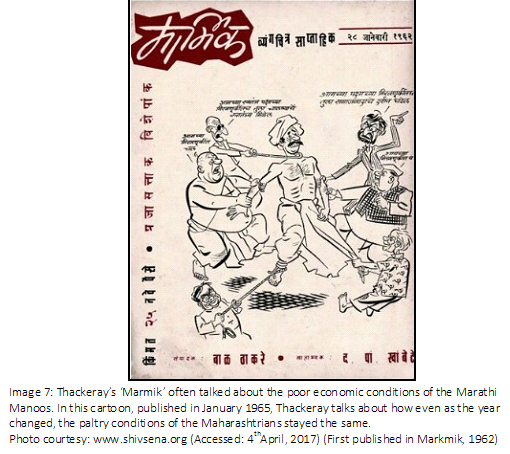

Through this paper, I attempt to reconstruct the period of uncertainty in the late 1960s that had become a part of the everyday for hundreds of South Indian families, including my own, living in Bombay. Stitched together with personal narratives and oral histories, I look at the mood of rebellion and anarchy that played a definitive role in the making and unmaking of the political history of Bombay as part of Shiv Sena’s flagship ‘Bajao Pungi, Hatao Lungi’ campaign. As a parallel narrative, I have textually analysed the cartoons illustrated by the party founder Bal Thackeray in his weekly magazine, Marmik, which attempted to incite the Marathi-speakers through the ominous portrayal of the ‘outsider’ in the city.

Keywords: Shiv Sena, outsider, identity, violence, urban politics, oral history, exclusion, resistance

Introduction

“In the calm and quiet of night, I went to the house of Ganpati Maratham, and greeted him with Namaskar, informing him that I had come to take his interview.

Ganpati looked at me with surprise and said, “Oh, after so many years the old Marathi language is again spoken today. How do you know this language?”

“I took the subject ‘Old Marathi language’ for my Ph.D.,”- I replied.

He said smiling, “Nowadays this language is never heard. In my childhood, Marathi was spoken in pure form; now that pure language is heard only in a small habitation of Chambal valley. A hundred years ago in Mumbai, Madrasi governors, mayors and sherrifs were appointed. The Marathi people of that time used to call these people outsiders. Then, the Madrasi lungi was a topic for fun. Today, everyone wears a lungi.”

“Yes,” I said, “Recently in a fancy dress competition, one man wearing a dhoti received a prize from the Governor… What a strange garment.”

–Bal Keshav Thackeray, on what Mumbai would become in AD 2065 if the ‘Madrasis’ took over the state,

Published in Marmik on August 15, 1965[1]

After having spent an entire day on the street, immersed in the emotionally-charged sights and sighs of a sea of mourners during the funeral procession of the Shiv Sena party founder Bal Keshav Thackeray on November 18, 2012, the atmosphere back home was remarkably distinct.

While my mother was glad that childhood fears of witnessing “Bombay burn if Thackeray dies” had not come true, my 86-year-old grandfather KK Ganapathy bore a perceptibly anxious look. As he watched Thackeray’s funeral procession inch towards the Shivaji Park ground live on the television set, my grandfather’s memories of pain, fear and uncertainty – experienced more than five decades ago – made a swift reappearance.

Recounting the horror of being accosted and abused by “hooligans” outside Dadar station in the early 1960s, and later, forcefully stripped in public in the latter half of the decade, my grandfather – who had shifted to Bombay from Palakkad, Kerala in 1953, rued about how such instances had become a part of the everyday for him. “The first time I was attacked, I was afraid and was taken aback by the strong words of disgust hurled at me by the hooligans, who called themselves the ‘locals’. I was very hurt, but chose to remain silent,” said Ganapathy. “However, when I was stripped in public the second time, I was extremely angry. When the hooligans abused and mocked me by asking me to ‘Get Out!’ I retorted by telling them that they could remove my dhoti[2], but would never be able to take me out of the city”.

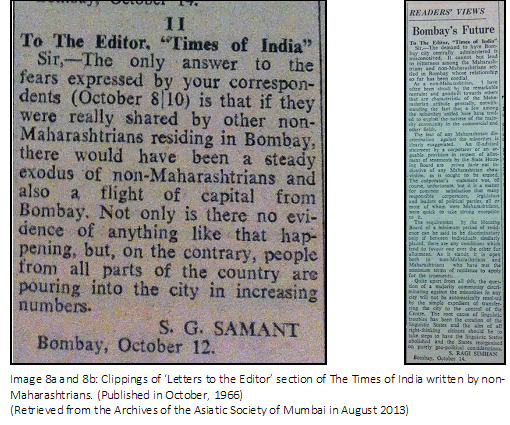

The Bombay of 1960s was a city frustrated with an unimpeded inflow of workers from other states, especially in the south. In 1961, Maharashtrians, who later came to be known as the ‘Sons of the Soil’, formed just 43% of Bombay’s population(Purandare 2012). Though no single non-Maharashtrian community gained majority in terms of number, together they were larger than that of the Maharashtrians. Thus, like my grandfather, several hundreds of South Indian families, who had moved in to Bombay in search of better lives and livelihoods, were suddenly grappling under the shadows of their own identities in the 1960s.

The garments they wore – questioned.

The vermilion on their forehead – mocked.

The language they spoke – scorned.

The money they earned – plundered.

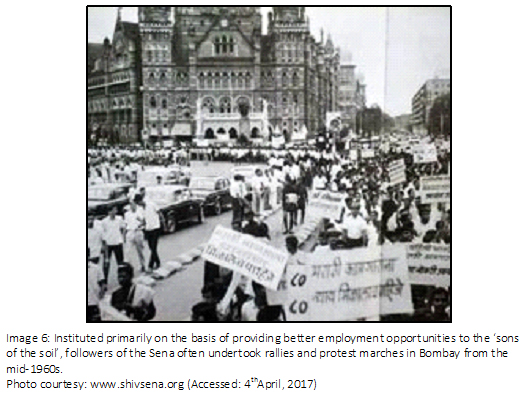

The mood created as a result of the excessive competition for jobs and housing was what fed into the ideology of the Shiv Sena at its inception. What initially began as sporadic events of anger and violence soon led to a full-blown, collective clash with the South Indians as a part of the ‘Bajao Pungi, Hatao Lungi’ campaign. Beyond the rhyme, the campaign slogan was carefully designed to insult the ‘outsider’ in the city. Pungi, a wind instrument used by snake charmers, is a reference to street art in Maharashtra[3], where in Garudi, a snake charmer blows the pungi in order to make the snake dance to his tunes. The Lungi refers to the four-yard-long garment, usually printed, traditionally worn by men from south India to cover theregions below the waist. Unlike the dhoti, which was worn by upper caste men such as priests and scholars, the lungi lacked social respectability. Considering the fact that the Sena itself was anchored in its Brahminical roots with most of its founding leaders belonging to the upper caste (Interview with Purandare; 2013), the campaign slogan was basically referring to the Lungi-wearers, the South Indians, as snakes who needed to be thrown out by the locals. Literally translated, the slogan meant ‘Blow the Pungi, Throw out the South Indian’.

This paper is an attempt to document those insecurities and fears of living as an “outsider” in a city that had been synonymous with “home”. It is also an attempt to trace the early beginnings of one of India’s largest regional parties, the Shiv Sena in Maharashtra, that has sought refuge in divisive politics ever since, nourished by issues of increasing migration, communal violence, poor civic amenities and lack of jobs for local people.

A Tale of Deliverance

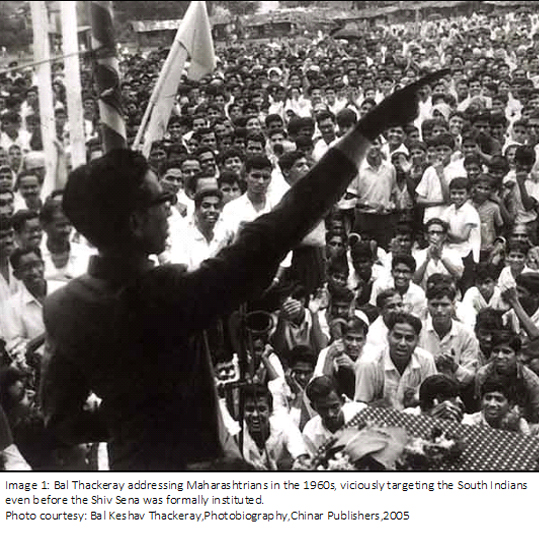

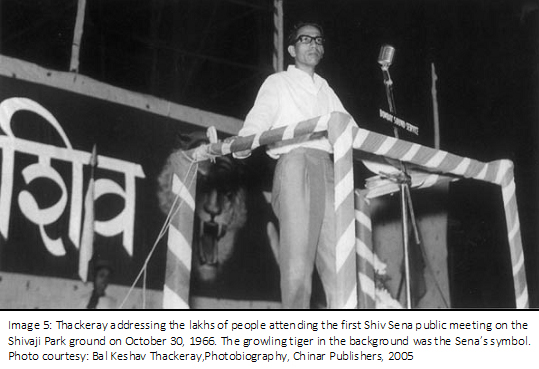

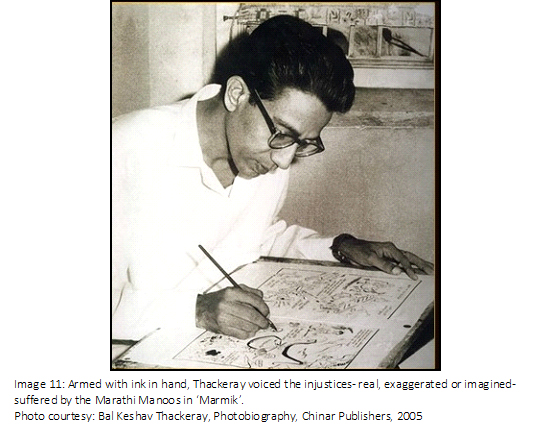

This violent form of politicised Marathi regionalism was commanded by Bal Keshav Thackeray, a political cartoonist, who formally instituted the Shiv Sena on19th June, 1966. The Sena arose directly from urban unemployment. It responded to a real demand, for the organisation gained immediate popularity among the working class Marathi-speaking population.

It started as an ‘interest group’ to articulate what was considered to be the legitimate demands of the Marathi-speaking people in Bombay. Maharashtra was constructed as the homeland of Marathi speakers and South Indians, who made up for 8.4% of the population in Bombay in 1961, were cast as ‘outsiders’, enjoying economic prosperity at the expense of the ‘native’ Maharashtrian (Banerji 1998).

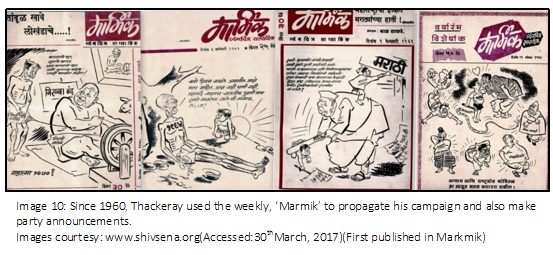

With a target audience – the Maharashtrians – that was spread out across the sprawling city, it became important for Thackeray to find a powerful medium to create the collective. Thus was born ‘Marmik’; Thackeray’s weekly publication that he used as a propaganda tool. Short, funny censures were made using humorous sketches and accounts of current events in Marathithat appealed to ordinary people. From 1963 onwards, the publication began to be known as much for its regular reproduction of the listings of Nairs, Menons, Shahs and Patels from Bombay’s telephone directory as it was for its satire. In fact, according to author and journalist Vaibhav Purandare, Marmik was so effective in highlighting alleged discriminations that its circulation nearly doubled in 1966: from 20,000 in the previous year, it leapt to 40,000 (Purandare; 2012: 4).

The original project evolved by ‘Dictator Thackeray’, as he has called himself, was fundamentally chauvinistic, but not primarily religious (Heuze 1992). South Indians, the usual explanation ran, had been migrating to Bombay and had begun to monopolize the office jobs in the city. As a result, the Maharashtrians were side-lined and were unable to compete with them. The reasons ranged from the fact that South Indians were more fluent in English, educated, and, in most cases, South Indians heading offices recruited only their own community members. Katsenstein(1973) in her paper, ‘Origins of Nativism: The Emergence of Shiv Sena in Bombay’, asserts how it was backed by the notion of threat posed by ‘outsiders’, Shiv Sena won the support of the Bombay Maharashtrian community.

Through provocative speeches and tongue-in-cheek cartoons and articles published in Marmik, the ideology of ‘Maharashtra for Maharashtrians’ was voiced. For example, between April and September 1967, lists of officers of businesses and institutions were printed showing Maharashtrians to be in a distinct minority, only 75 out of 1500 executives, vis-à-vis South Indians who occupied 70% jobs (Purandare 2012: 19).

The Sena, thus, became a topic of heated debate. Its activities, some outside the ambit of the law, continued to grow. One such action, which invited controversy, was an attack on a South Indian hotel in Kala Chowki in central Bombay in February 1967. Thirty-two persons were injured in the stone-throwing by Shiv Sainiks, and four Sena activists were arrested. Bal Thackeray, however, showered praise on the Sainiks involved in the attack (Purandare 2012). Though they did not carry lethal weapons, violence was their creed and integral to their demonstrations.

The public outcry against South Indians continued to be generated, backed by the use of strong headlines and cartoons. For instance, one of the headlines read: ‘Kaalcha Madrashi, thodyach divsat tupashi‘, which meant that the Madrasi, who came recently, has become rich soon. On June 5, 1966, before the official launch of the party, Thackeray published a box in Marmik and announced: “We will launch Shiv Sena soon to respond to the attacks of yandugundus [South Indians]. Have a look at next edition of Marmik” (Tare 2012).

In the weeks, months and years that followed, the streets of Bombay, which had earlier been calm, peaceful and united, had been divided into two – a city of the ‘locals’ and a city of the ‘outsiders’.

A Tale of the Ambiguous Local

In the mid-1930s, Advocate CD Seshadri’s father – a native of Kerala – moved to Bombay and set up a South Indian restaurant in the midst of a Maharashtrian-dominated area of south Bombay. The family-run restaurant, which was popular for its paper dosas and steamed idlis, was swarmed by huge crowds including many Maharashtrian families, through the week. Seshadri, who was born and bred in this area, spent most of his growing up years, interacting with his Maharashtrian neighbours, classmates and friends. He spoke fluently in Marathi, celebrated festivals such as Ganesh Chaturthi and Gudi Padwa with great fervour and spent several evenings devouring food in his own father’s restaurant with his Maharashtrian friends.

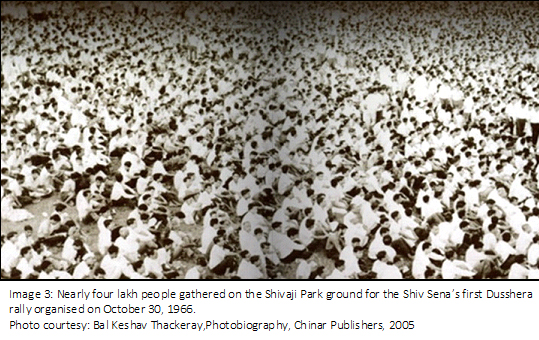

However, with the advent of Thackeray’s discourse against the ‘yandugundus’ – a jibe at the Tamil language – most South Indian-run restaurants became the easy targets of the vandals. Sena’s strategy to collect funds included forcible extraction under threat from South Indians, shopkeepers and hoteliers as protection money. (Gupta 1980) In fact, after Thackeray’s speech in October 1966, the crowd that had shown up for the rally on the Shivaji Park ground began vandalising Udipi restaurants as it dispersed, almost instantaneously marrying the new organisation’s image with its mascot – a growling tiger.

Seshadri’s family-run restaurant also met with a similar fate. The last nail on the coffin was the fact that the attack was carried out by vandals, which also included his “friends”.

I had previously been warned by a group of close Maharashtrian friends that our restaurant was on the hitlist of the Sena workers. Thus, a day in advance, we had moved the money from our cash box to lockers in our residence. On the day of the attack, I told my father to attend to our automobile business shop, while I stayed back in the restaurant. Since business was usual and there was no smell of threat, I decided to go to the automobile shop for a while. By the time I settled there, I received a phone call from my restaurant staff, informing me that a large group of Sainiks had barged into our restaurant, damaged property and were trying to escape with the cash box. I rushed to the restaurant, only to find property severely damaged and the cash box thrown on the ground outside. Since I had been informed earlier, there was only six rupees in the cashbox, which probably, infuriated the Sainiks further,

recounted Seshadri. In the following months, the family was compelled to shut down the restaurant after receiving incessant threats.

The incident took the family by storm. Barring the damages that were incurred, it was the underlying current of an ‘identity of the local’, which continues to hurt Seshadri even today. In his own words

After the incident, even the local cops took more than two hours to come to our rescue. I kept questioning the reasons for being compelled to shut down the restaurant and live under the blanket of extreme fear. For someone, who spoke and lived with Maharashtrians, it hurt me deeply to be targeted by people whom I considered my own. Despite being able to speak in fluent Marathi, I reckon I was targeted only because it was not my mother tongue.

So, who was the ‘local’ that the Shiv Sena was fighting for?

According to Purandare (2012), exactly a month after the Sena’s inception, directive principles were laid down for those desirous of joining it. Anyone wanting to be a Sainik had to take an oath in which the following principles are enshrined:

- The Marathi people should help each other, and see that the Marathi manoos takes the path to prosperity.

- Maharashtrians shouldn’t sell their property to outsiders, and if any local is found doing so, the nearest shakha should be immediately informed.

- As far as possible, Marathi shopkeepers should buy their goods only from Marathi wholesale traders and treat customers with decorum.

- Maharashtrians who have their own establishments should only employ sons of the soil.

- Young Marathi-speaking boys should develop excellent communication skills in the English language, and learn English typing as well.

- Casting away laziness, the Marathi people should form their own cooperative housing societies, and they should show willingness to go to any place for a job.

- Celebrate Marathi festivals and functions with Marathi brothers and sisters by participating eagerly in huge numbers.

- Locals should involve themselves in the activities of institutions, schools, ashrams, etc. belonging to Maharashtrians and donate generously for their cause.

- Boycott all Udipi hotels and do not buy anything from shops of non-Maharashtrians.

- Don’t discourage the Marathi-speaking people involved in business and other professions, and keep them from losing heart;

Instead, extend as much help as you can.

- Do not behave arrogantly and crudely with your own Marathi brethren, and in case any of them faces any difficulty, others should collectively support him.(Purandare 2012: 22-23)

However, the Shiv Sena that was organized originally to protect the interests of the ‘local people’, a term that had a range of meanings – one whose mother tongue is Marathi; one who has lived in Maharashtra or Bombay for ten or fifteen years; one who identifies with the ‘joys and sorrows’ of Maharashtra – conveniently varied in usage with the Shiv Sena’s changing perceptions of political feasibility.

Thus, despite speaking fluent Marathi, acknowledging and celebrating Marathi cultures, and living in the city for several decades, Seshadri’s family like several other South Indian families, were considered to be ‘non-Maharashtrians’, ‘outsiders’, and therefore, a threat.

A Tale of Sub-Nationalism

He spoke in a language that was distinct from Tamil, had neither lived in Tamil Nadu nor had any relatives staying even remotely close to it. Yet, Chakradhar Gundetty’s family, which had moved in to Bombay from Nizamabad in Andhra Pradesh in 1945, were christened as ‘Madrasis’ and their language, ‘Yandugundu’. “The Sena thought of all people hailing from South India as one group. Anyone who spoke in a language that was non-Marathi or had a perceptible accent was immediately called a lungi-wallah or a Madrasi,” Gundetty said.

In reality, people hailing from the four states located in the south of India – Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka – had distinct identities, practiced diverse cultural rituals and were employed in varied occupations. While people from Kerala worked as coconut vendors, stenographers or as office boys, the Shetty clan and the other Kannadigas worked in the hotel industry. The Tamilians were mainly found working in banks or in enterprises holding clerical positions, while individuals from Andhra Pradesh were engaged in more labour-centric occupations such as construction work.

Journalist Kumar Ketkar (2012) who attended the Sena’s first meeting along with “hundreds and thousands of other young boys”, later wrote: “To him (Bal Thackeray) all southerners were Madrasis, and all northerners, Bhaiyyas… He thundered against Madrasis for snatching jobs that he thought belonged to the Marathi people. His philistinism was transparent as much as his political innocence.”

Making peace with a fractured and misplaced identity was never an easy task for families like Gundetty’s. First, they had to deal with the regional slurs that were directed at them for being ‘non-Maharashtrian’ despite making Bombay their home and accepting the city’s culture. Second, they had to constantly tackle the misplaced identity imposed on them of being a Madrasi.Thus, it was a dual identity crisis – of being a Non-Maharashtrian and a Madrasi.

So, who exactly was this ‘Madrasi’ monster gobbling up the life and livelihood of the local ‘Marathi Manoos’[4]? According to the party workers, anybody who came from any of the four southern states of the country – Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Kerala[5]– was branded a Madrasi. It didn’t matter whetherthey spoke even two words of Tamil or not. While referring to the coinage of the term in the context of Bombay Cinema[6], Ravi Vasudevan (2012: 102) claims that the term ‘Madrasi’ dismissively collapses the entire southern region of India, and has been used in “stereotypical ways under an overarching North Indian, majoritarian Hindu identity”. Often termed ‘derogatory’, the debate surrounding the usage of the term continues to remain relevant even today.[7]

In its attempt to create a clear-cut hero and villain – the Marathi Manoos and the Madrasi respectively – the Sena failed to address crucial indicators such as caste. Thus, the ‘lungi’ and ‘dhoti’ (or veshti), which have historically been a premise for caste-based exclusion in Tamil Nadu, were all pushed under the identity of the all-encompassing ‘Madrasi’. In fact, the term ‘Madrasi’ itself is a part of the vocabulary of discrimination. According to author Lloyd I Rudolph, (1961: 289) who has studied populist radicalism within the framework of Dravidian politics in Madras, the ‘true’ Madrasi is a ‘Tamil-speaking Dravidian’ whose race and culture are to be ‘sharply distinguished’ from the ‘Brahmin’s Indo-Aryan and Sanskritic’ racial and cultural roots. Thus, by adopting naïve and/or intentional universalisms of ‘Madrasis’, the campaign can be criticised for sweeping caste differentiations under the carpet.This omission of caste from its campaign discourse can also be linked to Sena’s political history:all the top Sena leaders belonged to the upper caste.The party thus, strategically maintained an avowed distance from class and caste politics (Interview with Purandare 2013). It drew its strength from Marathi migrants from the Konkan, who formed the party’s base.

The third crisis emerged from the very basis of the organisation’s ideology of counting unemployment in ethnic terms. In fact, politics, not economics or culture, was in command. Thackeray referred to the injustices – real, exaggerated, or imagined – suffered by Marathi speakers in order to constitute them as the only legitimate people. According to Gundetty, his father along with several other uneducated natives of Andhra Pradesh moved in to Bombay to find jobs in mills or construction sites. Thus, the blanket claim that all South Indians were encroaching on white collar jobs meant for the Maharashtrians was an exaggeration.

However, this form of sub-nationalist politics was not restricted to the Shiv Sena alone. The mid-sixties saw the rise of many local and regional leaders, and political outfits. In Tamil Nadu, the DMK came to power, overthrowing the Congress for good. In Punjab, the Akali Dal established its roots. In West Bengal, the Communists became more influential. The Naxalite movement too came on the national scene in 1969-70. In Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, new opposition fronts were born in the 1967 elections. Though the Shiv Sena could not become a regional party in the classical sense, Thackeray roared just when this mood of rebellion and anarchy had begun to spread. According to political journalist Kumar Ketkar(as quoted in Purandare; 2012: 26), many a commentator saw in the rise of the Shiv Sena, “a new militant Maharashtra”.

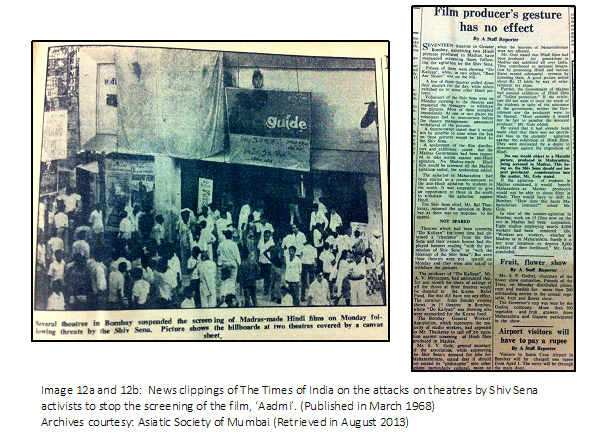

Thackeray’s campaign against the South Indians, received a fillip early in 1968. Following the 1965 riots in Tamil Nadu regarding the imposition of Hindi in the state, cinema houses in Madras had taken a decision not to screen Hindi films. Piggybacking on this decision to promote his own agenda, the Sena chief, in Bombay, set out to squash the outburst of nativist sentiments in southern India. He appealed to owners of Bombay theatres to stop screening films made in the south.

When the appeal did not work, coercive action was taken. In February, 1968, Sena activists attacked Ganesh Talkies in Lalbaug and stopped the screening of the film, ‘Aadmi’. Thackeray’s argument was that South Indian filmmakers earned money in Bombay and took it down south. Eventually, a ‘total ban’ on films made in South India became operative on March 16.

The Times of India (March, 1968) carried stories on its first page during the entire controversy along with side stories in its inside pages. It came down heavily on the Sena by interviewing members of workers’ associations. For instance, in a news report carried on March 10, 1968, SV Gole, general secretary of Bombay Workers’ Films Association has been quoted as saying, “No one would object to a Marathi picture, produced in Maharashtra, being screened in Madras. This being so, the Shiv Sena should not import provincial considerations into the matter…Workers are workers, whether in Madras or in Maharashtra” (The Times of India March,1968).

However, Marmik reported otherwise. Welcoming the Sena stand, a section of the Bombay film fraternity felicitated Thackeray in the same month. Marmik reported: “To see that the ban was properly implemented, Sainiks visited quite a few cinema houses…the theatre owners said they had themselves stopped showing films from South India.” (Cited in Purandare; 2012: 54) Thus, Thackeray’s long-standing influence in the Bombay film industry also began on the anti-South Indian stand.

The reasons for this form of ethnicity-driven, regional politics practiced by the Sena, however, can be traced back to the dissolution of the Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti after the creation of Maharashtra in 1960. At that time, with the Indian economy suffering from a financial slowdown, the unemployment rates including among the middle-class Maharashtrians was high. It was for the first time, Maharashtrians were developing political will, which encouraged them to find jobs and understand the reasons for their poverty.

Thus, when Thackeray shouted from the rooftop, voicing the inner concerns of the ‘sons of the soil’ and telling them that it was the South Indians who had stolen their livelihoods, their enemy now had a well-defined identity: A lungi-clad Madrasi speaking ‘yandugundu’.

A Tale of Negotiation

Living amidst the echoes of the ‘Bajao Pungi, Hatao Lungi’ slogan, the fears of being cornered, mocked and beaten up in public, and the trauma of being called an ‘outsider’ or ‘threat’ in your own country was an ordeal for the South Indians in Bombay at several levels.

Parents refused to send their children to schools, the men usually moved around in groups, and families settled down in ‘safe areas’, which housed families that spoke the same language, hailed from the same regions and experienced the same fears. For instance, the Telugu-speaking population, moved in to areas in Kamathipura and Worli’s BDD Chawls and the Tamil-speakers resided in Matunga, Sion and parts of Worli. There were conscious choices made to stay away from Marathi-dominated regions such as Parel, parts of Dadar and Girgaum. Thus, it was inevitable for the South Indians to bring about modifications in their lives and lifestyles- economic, social, political and cultural.

In the case of Vimala Parameshwaran, who had been residing in Thackeray’s neighbourhood even before the campaign had been launched, instances of thod phod (vandalism) were common. “As a neighbour, Thackeray had always been soft-spoken. When he started gaining power, our interactions had become limited. However, there was no fear from him, and in fact, it was only his followers who would indulge in anti-social activities.” Parameshwaran (Interview in 2013) said.

However, it was for fear of being caught unawares by the Sainiks that the family decided to do away with the ‘Iyer’ surname, which was so far, a clear indication of their ‘Madrasi’ identity. For others, such as Ganapathy, who had personally been a victim of the Sena’s antics two times in the past, it was a fresh attack on his musician friend, which brought him to boil. A renowned musician from Madras had come to Bombay for a concert, and was residing in Ganapathy’s house. One evening, when the musician who wore a white dhoti and had applied sacred ash on his forehead, was walking down the streets of Shivaji Park, a few local boys cornered him and made fun of him. Shocked, unaware and extremely afraid, the musician could not retaliate because he did not speak the language. While he was trying to explain to them that he was in the city only for a concert and did not reside here, the locals pulled down his dhoti, laughed, and ran away. The musician, who was completely numb by this point, began to run helter-skelterhoping to seek refuge. A few good Samaritans, who noticed him on the street came to his help, took him to a nearby shop and purchased a pair of pyjamas for him. By the time he reached home, he was clearly disillusioned beyond belief.

It was at this moment that Ganapthy wrote a letter to Thackeray, questioning the rationale behind insulting fellow-Indians:

Instead of insulting the South Indians, why can’t you instead, focus your energy on educating the Maharashtrians and make them competitive enough for the jobs? We are living in Bombay as legal residents, paying taxes and even accepting the local cultures. Why are you threatening us?

Though Ganapathy never received a response from the former Sena supremo, the situation soon began to change for the South Indians. There was anger and sense of deep frustration that had begun to emerge among them as they felt that they were being incongruously targeted. With the police (fearing the Sainiks themselves) not coming to their timely rescue, the South Indians negotiated their spaces by countering the attacks in groups.

For instance, Gundetty recounted an incident inside an Udipi restaurant located near Century Mills, which was attacked by the Sainiks. A group of Sainiks barged into the restaurant with the intention of terrorising and looting the owners. The restaurant waiters managed to pull down the shutters, while the cooks in the kitchen used their presence of mind and boiled the oil. The restaurant owners then threatened the Sainiks that they would hurl the oil at them if they did not leave from the restaurant. This threat was enough for the Sainiks to flee.

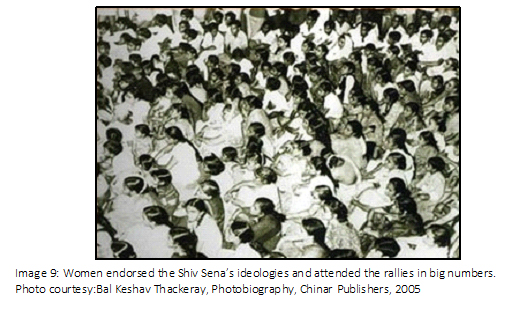

However, even though there were innumerable instances of such violent outbreaks, Heuze (1992) in the article titled ‘Shiv Sena and National Hinduism’ states that the women and members of the lower castes were out of the Sena scanner. There were no instances of sexual harassment or caste-based attacks. In fact, during the course of interviews, it was brought to light that the women felt safe during that period and even attended the Sena rallies in big numbers.

The victims, thus, were mainly employed, South Indian men.

The reasons, in my opinion, for this ideological-cum-political decision could be summarised as follows:

- The Sena’s politics emerged from the ‘Dada politics’, which stated that the men were the protectors of women and hence, their dignity had to be upheld.

- Politically, differentiating the lower-castes from the larger community would have narrowed down the Sena’s reach. Hence, they decided to focus on the larger group of ‘Madrasis’ – which was also a relatively small section of the larger Indian community.

A Tale of Changing Tides

By the mid-1970s, Thackeray realised that the only way to enter national politics, would be by extending his reach. The organisation was formulated in a way to reach out a larger section of the population and also, consolidate itself (Gupta 1980). Thus, Sena’s definition of the outsiders slowly began to change and other issues were brought to the fore. The Sena, according to Katzenstein (1973), became a fierce critic of ‘anti-nationalism’.

In 1972, Thackeray set up his Sthaniya Lok Adhikar Samitis (local people’s rights committees) in banks and government offices, and began ensuring jobs for Marathi-speaking youth (Punwani 2012). The fear of violence and his own clout forced the ruling Congress government to issue a directive to all employers in 1973 that 60% of managerial jobs and 90% of other lower category jobs in Bombay be given to those domiciled in Maharashtra for 15 years. Thus, Madrasis, who were so far considered a ‘threat’, were set free.

There were new enemies: Communists and Muslims.

Shiv Sainiks attacked the Communist Party of India’s (CPI) office in the working-class area of Parel, and violently engineered splits in CPI unions. For Thackeray, leftists were anti-national. In fact, when Sena’s Wamanrao Mahadik won the by-election in 1970 to become the party’s first MLA, Thackeray while addressing the party’s victory rally said, “This is our dharmyudh. It is the Shiv Sena’s aim to destroy all those who are not loyal to the nation…Our victory is the victory of Hindutva.” (Purandare 2012: 61)

Meanwhile, unlike the South Indians, Muslims remained Thackeray’s target till the very end. The party engaged in large-scale looting and street violence during the 1992-1993 riots in Bombay during the Babri Masjid demolition (Punwani 2012). Thus, with the emergence of a common enemy, the Sena also defined a common identity for the Marathi Manoos and the Madrasi: ‘Hindu Nationals’.

In its political ploy to create exclusions, the Shiv Sena often switched tracks. Taking a 180 degree turn from its violent protests against the Madrasis, the party began to rope in South Indians as party members. In 2008, for instance, the party floated the Shiv Sena Kerala Mandal in Thane to garner votes from Malayalam speakers (Mumbai Mirror 2012). This also came at a time when the Sena was heralding its anti-Bhaiyya campaign against the North Indians. Moreover, in 2014, ‘Captain’ Tamil Selvam, a Bharatiya Janata Party candidate, became the first Tamil-speaking Member of the Legislative Assembly in Mumbai (Nadar 2014) representing the Sion-Koliwada constituency.

Four decades ago, one could have never imagined that the lungi-wearing, yandugundu-speaking, job-snatching Madrasi, would ever be able to walk carefree on the street, let alone be elected to the Maharashtra State Government.

Reetika Revathy Subramanian completed her Masters in Media and Cultural Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. Moving from journalism to gender research, she has worked extensively in the rural belt of south Rajasthan on issues related to sexual violence and trafficking. She is currently studying for an MPhil in Multi-disciplinary Gender Studies at the University of Cambridge Centre for Gender Studies

References

Banerji, Sikata (1998) “ Political Secularization and the Future of Secular Democracy in India: The Case of Maharashtra”, Asian Survey. 38 (10): 907-911.University of California Press.

Gupta, Dipankar (1980) “The Shiv Sena Movement: Its Organisation and Operation: Part Two”,Social Scientist 8 (11): 32-43.

Heuze, Gerard (1992) “Shiv Sena and ‘National’ Hinduism.” Economic and Political Weekly. 27(40): 2189-2195.

Joshi, Ram (1970) “The Shiv Sena: A Movement in Search of Legitimacy” Asian Survey. 10 (11): 967-978.. University of California Press.

Katzenstein, Mary Fainsod (1973) “Origins of Nativism: The Emergence of Shiv Sena in Bombay”, Asian Survey. 13 (4): 386-399.. University of California Press.

Ketkar, Kumar (2012, 24thNovember) “Senior journalist Kumar Ketkar’s eulogy to the godfather of discord, Bal Thackeray”,India Today. Available from: http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/senior-journalist-kumar-ketkars-eulogy-to-the-godfather-of-discord-bal-thackeray/1/234457.html [ Accessed: 1stSeptember 2013]

Ketkar, Kumar (2012, 17th November) “Bal Thackeray’s hallmark was his spontaneity. He liked to make statements that shocked and made headlines”,Tehelka.Available from: http://archive.tehelka.com/story_main54.asp?filename=Ws171112Appraisal.asp [Accessed: 28th August 2013]

Mumbai Mirror (2012, 4th November) “Sena woos South Indians”,Mumbai Mirror. Available from: http://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/other/Sena-woos-South-Indians/amp_articleshow/15866300.cms [Accessed: 18th January 2017]

Nadar, G (2014, 12thOctober) “Once south Indians were beaten up in Mumbai; now the city has a Tamil MLA!”,Rediff.com.Available from:http://www.rediff.com/news/report/once-south-indians-were-beaten-up-in-mumbai-now-the-city-has-a-tamil-mla/20141020.htm [Accessed: 19thJanuary 2017]

Prakash, G (2012, 17thNovember) “Bal Thackeray: The original angry young man”,HT Live Mint. Available from: http://www.livemint.com/Specials/5lVU9V2vB1Xcexv92mVmAK/The-original-angry-young-man.html [Accessed: 4thSeptember 2013]

Punvani, J (2012) “India: Bal Thackeray – A Politics of Violence”, South Asia Citizens Web. Available from:http://www.sacw.net/article3359.html [ Accessed: 20th January 2017]

Purandare, Vaibhav (2012) Bal Thackeray & The Rise of The Shiv Sena, Mumbai: Roli Books

Rudolph, L I (1961) “Urban Life and Populist Radicalism: Dravidian Politics in Madras”,The Journal of Asian Studies. 20(3): 283-297.

Tare, K (2012, 17thNovember) “Obituary: Bal Thackeray-the tiger who ruled Mumbai”,India Today. Available from: http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/bal-keshav-thackeray-obituary/1/229596.html [Accessed: 16thAugust 2013]

Times of India (1968, 10th March). “Film producer’s gesture has no effect.” Times of India. Retrieved from Asiatic Society of Mumbai in August 2013.

Vasudevan, R., 2011. The Cultural Politics of Address in a ‘Transitional’Cinema. In The Melodramatic Public (pp. 98-129). Palgrave Macmillan US.

INTERVIEWS:

Ganapathy, KK (2013, August 28). (R Subramanian, Interviewer)

Gundetty, Chakradhar (2013, August 31). (R Subramanian, Interviewer)

Seshadri, CD (2013, September 2). (R Subramanian, Interviewer)

Seshadri, Vimala (2013, September 2). (R Subramanian, Interviewer)

Purandare, Vaibhav (2013, September 3). (R Subramanian, Interviewer)

[1] Translated from Marathi to English by Vaibhav Purandare in ‘Bal Thackeray & The Rise of The Shiv Sena’ (2012: 5-6)

[2]Dhoti, also referred to as Veshti in Tamil, is a four-yard-long garment worn by men to cover the regions below the waist particularly in the states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh. It is draped in different styles, and is called differently in each of these states. Made of silk or cotton, it is usually worn by privileged, upper-caste men.

[3] Author Anne Feldhaus describes the ‘pungi’ in the footnotes for her chapter, ‘Mountains, Rivers and Shiva: Continuity Among Religious Media in Maharashtra’ published in ‘Intersections: Socio-cultural trends in Maharashtra’, a compilation of essays edited by Meera Kosambi.

[4]Literally translated as ‘Marathi People’, the term is often used in political contexts to refer to native residents of Maharashtra, for whom Marathi is their mother tongue.

5 These states made up part of the former Madras Presidency, an administrative subdivision of British India.

6 Thackeray maintained a long-standing influence over the Bombay film industry, which also was an outcome of the anti-South Indian movement.

7In 2014, four performers from a group called Stray Factory produced a video on YouTube called ‘Not Madrasi, Just Padosi (neighbor)’ to talk about the incorrect usage of the term.