The Memories of a Spark: Reconstructing the 1965 riots in Madurai against the imposition of Hindi

Sriram Mohan

Abstract

The paper aims to capture the synthesis and popular reconstruction of one of independent India’s earliest instances of large-scale violence over the emotive issue of language, i.e., the January 1965 Madurai riots that occurred on the day before the fifteenth anniversary of India becoming a republic, against the imposition of Hindi as the sole official language of the union of India. The seeds of the anti-Hindi protests in the state of Madras were sown in the 1930s and its revival in the 1960s had widespread social, cultural and political ramifications. This paper seeks to explore how culture, identity, ideology and power relations weighed in on the socio-ethnic unity of the nation state at that time, from the perspective of lived experience (oral histories) and through an analysis of the media representation of the riots and its outcomes.

Keywords: agitations, anti-Hindi, identity, language, media, memory, nation, national language, riots

The spark and the fire…

As a young boy in secondary school, I remember thinking of history as a series of interesting tales being narrated by someone who had an inexplicable obsession with dates. The days, the months and the years mattered little to me and I conveniently ignored them whenever possible, choosing to be affected by the powerful stories instead. As I grew older, the potential of a date to signify an event, a happening, an occurrence became clearer to me. September 11th became short-hand for the threat of terrorism. December 26th turned into a signifier for the terrible tsunami. And January 26th had been equated to, in my mind as it is likely to be in the others from my country, the Republic Day of India, a national holiday which could legitimately be spent watching the grand parade in New Delhi, on television.

In 1965, however, the 26th of January and the days leading up to it adopted a form larger than that of an occasion designed to showcase the ceremonious muscle-flexing undertaken by a young nation. In that year, Hindi was due to become the official language of the union of India on Republic Day. The run-up to the ‘cut-off’ date saw hectic activity against the adoption of Hindi in the non-Hindi speaking parts of the country, especially in the state of Madras whose people were long opposed to what they saw as the ‘imposition’ of Hindi.

This sentiment was particularly strong amongst the Tamil-speaking student population, which saw the adoption of Hindi as an infliction of severe disability on their plans of studying further in English and acquiring highly-coveted government jobs. Realizing that the discontent brewing could translate into direct action with the support of the Dravidian parties, M.Bhaktavatsalam of the Congress Party, the Chief Minister of Madras at that time, warned students against participating in politics and made it amply clear that ‘agitations on Republic Day would not be tolerated’ (Hardgrave, 1965).

To avoid the trouble that was associated with protesting on Republic Day, students across Tamilnadu decided to advance their agitation against Hindi by a day, i.e., to the 25th of January, 1965. In Madurai, as across the state of Madras, students started preparing for the protests by making posters and signboards with messages such as “Down with Hindi!” and “Hindi Never, English Ever!” (Hardgrave, 1965). On the morning of 25th of January, a large group of students took out a procession towards Thilagar thidal (Tilak Maidan), where they planned to burn Part XVII of the Indian Constitution which contained the provisions and articles associated with Hindi becoming the sole official language. The procession passed through the North Masi veedhi (street), which also happened to house the district office of the Congress Party. Multiple versions emerge from this point onwards. Some claim that the Congress office was stoned by the students taking part in the march and the Congress party workers then got into a brawl with the protestors (Forrester, 1966).

Others claim that Congress “volunteers” arrived in a jeep, screaming insults and hurling obscenities at the students and that the students retaliated by throwing slippers at the Congress workers (“Interview with Pa. Seyaprakasam”, 2008). The thus-provoked Congress men reportedly ran back into the Party’s office, returned with aruval (sickles used for cutting paddy) and attacked the students, wounding seven. Enraged, the students set fire to the pandal outside the Congress office, constructed for the Republic day celebrations due to be held the next day and then, set fire to the jeep as well (Hardgrave, 1965). When news of the attack spread, riots broke out in Madurai and various other parts of the State. As tensions escalated, students brought down flag poles of the Congress party all over Madurai (“Interview with Pa. Seyaprakasam”, 2008).

In the weeks that followed, anti-Hindi demonstrations and rioting took place all over the state of Madras, with more than sixty people being shot in police-firings, and unofficial reports placing the death toll at as high as three hundred. Two young men poured gasoline upon their bodies and immolated themselves on Republic Day itself. Hindi books were burned, and the Hindi signs in post offices and railway stations were defaced or ripped down (Guha, 2005). All colleges and schools remained shut, and the students’ demonstrations “gave way to the mob violence of rowdies” (Hardgrave, 1965).

As the rioting continued, Lal Bahadur Shastri, the Prime Minister of India and the leader of the Congress Party after Nehru, was placed in the hot spot. On the 11th of February 1965, “his hand was forced” by the resignation of two Union Ministers from Madras, namely C Subramaniam and O V Alagesan. That evening, he went on All India Radio and assured the people that he would abide by Nehru’s promise to keep English in use as long as the people wanted (Guha, 2005).

The synthesis of the spark…

The chain of events, leading to the 15th Republic Day of India being burdened with a significance that extended well beyond the idea of national pride and extending to include the ghastly violence that occurred subsequently, can be traced back to 1937. The first anti-Hindi agitation took place that year, in response to the introduction of Hindi as a compulsory subject in the schools of the Madras Presidency by the first Indian National Congress government led by C. Rajagopalachari (More, 1997). This measure was severely opposed by E V Ramasamy Naicker1 (popularly known as Periyar) and the Justice Party (later Dravidar Kazhagam), who then started agitations against the move, in the forms of protests marches, fasts and pickets.

The move to make Hindi compulsory was later withdrawn by Lord Erskine, the Governor of Madras, in February 1940, a development that was sparked off by resignation of the Congress Government in October 1939 protesting the involvement of India in World War II. Two days after the resignation of the Congress government, Periyar halted the agitation that had gone on for close to three years and asked the governor to withdraw the order requiring Hindi to be made compulsory in schools, a wish that was fulfilled four months later by Lord Erskine. Similar waves of protests, though sporadic in nature, occurred between 1946 and 1948 as well (Sundararajan, 1989). The year of 1949 was another pivotal point in this ‘anti-Hindi’ history, as this was the year in which the Constituent Assembly of India drafted Part XVII of the Indian Constitution. Part XVII defined Hindi in the Devanagari script as the official language of the union of India and allowed (through Article 343) the use of English as an associate language for all official purposes, with the time period for such use being limited to 15 years.

There was no mention of a “national” language, however. The Constituent Assembly, after much debate, had limited itself to defining only the “official” languages (Kodanda Rao, 1969). The ratified Constitution of India, bearing these frameworks, became operational on January 26th, 1950. Fifteen years later, the ‘grace period,’ which allowed for the use of English along with Hindi in the communication between the centre and the states and also, between the different states, came to an end. On January 26th, 1965, Hindi was poised to become the sole official language of India, in pursuance of Article 343 of the Constitution. The riots in Madurai occurred a day prior to this development and sparked off violence all over the state of Madras, throwing the plans of the Congress government at the centre and at the state, completely out of gear.

The significance of the spark…

The riots that occurred in Madurai on the 25th of January 1965 were an exceptional event with respect to the implications that they have had, some of which are felt even today in the politics of Tamilnadu. The Prime Minister’s reassurance in February 1965 did bring down the intensity of the violence and placate the students who protested. But it was a classic case of ‘too little, too late’ for the Congress in Tamilnadu. The riots that started in Madurai and spread across the state of Madras helped establish the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), a break-away faction of the Dravida Kazhagam (DK) headed by Periyar, as ‘the coming party in Madras politics.’

In the assembly elections conducted in 1967, the DMK, under Annadurai’s leadership, achieved victory on the wave of anti-Hindi resentment, which had begun to receive anti-Congress colour. The Congress was routed and has since remained a marginal force in Tamilnadu politics, without managing to capture power at the state level even once (Guha, 2005). In fact, an all-time high voter turnout of 76.56% was seen during the state elections in 1967 when DMK wrested power from Congress (Gunasekaran, 2009). The agitations also resulted in the passage of Official Languages Act of 1963 and its amendment in 1967, thereby solidifying the use of English as an official language. Thus, the agitations brought about the “virtual indefinite policy of bilingualism” of the Indian union (Simpson, 2007).

Reading the spark…

The various narratives of the 1965 Madurai riots play out through a tedious web of convergence and divergence. The different accounts seem to converge solely on the fact that a great deal of violence ensued, leading to extensive loss of life and property. However, the accounts assume positions of infinite divergence when it comes to questions of who caused the violence, who inflicted it upon whom, who benefited, who lost, why it occurred when it did, how the riots managed to assume such epic proportions in a short span of time, who was responsible for enabling this magnification and towards what end, what are the stories that have been repeated, to what effect and by whom, what are the silences that have been ensured over the years and by whom.

In attempting to answer these questions, one notices the multiple binaries that emerge between the various frames through which the 1965 Madurai riots have traditionally been viewed. Be it nationalism, regionalism, lingual chauvinism or casteism, the theories that have been put forth have proved inadequate to help us comprehend the causes and effects of the incident in its entirety.

This incomplete understanding can be attributed both to the fact that the ramifications of the incident are still being experienced, despite claims stating otherwise and the opinion that all of the frames used insofar to comprehend the riots and its aftermath have been devoid of what may be referred to as the ‘human dimensions’ (Butalia, 1995). Even in the odd instance where such dimensions have been built into the narrative, they have been used to further an ideology, rather than to acquire a more experiential understanding. Therefore, it would be instructive to examine the aforementioned questions, and frames, and their bearing on the narratives that have emerged (and that have not) by corresponding them with interviews of people who were affected by the incident in some manner, readings of the media coverage of that time and other representations of the same in popular culture, so as to arrive at a reconstruction of 1965 Madurai riots that is more inclusive of such divergent positions.

The headlines from one day (28th January 1965; there was no issue put out on the 27th) of the leading English daily in the Madras state, The Hindu, illustrate a portion of the story (Guha, 2005):

Total hartal in Coimbatore

Advocates abstain from work

Students fast in batches

Peaceful strike in Madurai

Lathi-charge in Villupuram

Tear-gas used in Uthamapalyam

The reportage in The Hindu focussed on the violence and the methods used by the state to quell such violence, an example of the ‘chaos versus order’ binary at work. The Hindu also published a number of engaging editorial pieces about the issue that captured multiple dimensions of the language debate, from a politico-economic perspective (Guha, 2005).

The New York Times also published two stories on the violence in the span of one week, chosing to stay away from the tangled heap of hopes, aspirations and ambitions involved in the issue and instead focus on youth getting involved in violence and a desecration of Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan’s memorial library in his ancestral home. The headlines of the two stories are given below (1965):

Madras Youths Again Stage Violent Anti-Hindi Protests

Anti-Hindi Mob Raids Home Where President Was Born

This line of narrative seemingly seeks to paint a picture of the violence as the actions of an unruly ‘anti-national’ mob and as Pandian (1996: 3323) suggests, “the ontological primacy given to ‘nation’ in such narratives invests the language issue with a singular connotation, i e. as against the nation, and denies its other possible connotations.”

The Time magazine contributed to the coverage of the riots as well. The magazine published two stories, one on February 19th 1965 and another on March 5th 1965, talking about the socio-economic repercussions of an adoption of Hindi (“India: The Force of Words”, 1965) and India’s inability to transcend English (“India: Retreat to English”, 1965). The stories also pegged the death toll at 60 and reported five cases of self-immolation, a significant difference from the official version of two deaths through self immolation (Hardgrave, 1965).

Hearing the spark…

While looking at the narratives of the event, I realised that it was all too easy, as Amin (1998: xiv) points out, to “give the lie to the self-image of Indian nationalism.” I believe that interviewing those who lived in the state of Madras during the Madurai riots of 1965 helped me transcend some of these traps. In order to understand the effects of the Madurai riots as a starting point for a larger wave of violence, I spoke to Ramanathan, an entrepreneur based in Chennai. Ramanathan was 15 years old and in high school in 1965, when the violence unfolded.

He was not a learner of Hindi, opting to study English, Tamil and Sanskrit instead in a Brahmin-run institution called P.S. High School. Ramanathan recounted the caste angle to the protests. “I belonged to a middle-class Brahmin family and participating in protests was a strict no-no, as far as my father was concerned. The boys belonging to the non-Brahmin castes, however, participated extensively. I remember that, in the days leading up to the Republic Day in 1965, there used to be protests every other morning. We’d be in our classes, while some of the students and a few DMK supporters would be taking out a rally. We’d look through our windows and get reprimanded by our Sanskrit teacher for doing so. Once when the din of the protests began to drown out of the voice of the Sanskrit teacher, all of us ran to the window to see what was going on. At that point, we noticed our Tamil teachers joining the demonstration, much to the consternation of our Sanskrit teacher. This was just a couple of days before the Madurai incident.” (Ramanathan, 2012).

The involvement of students of a particular caste, class and gender denomination dominates the different narratives characterizing the Madurai riot and its aftermath. That the protests were largely carried out by male, non-Brahmin students belonging to the lower-middle class is a recurrent assertion across narratives. In addition, the construction of the incident at Madurai as solely a student versus Congressmen tiff is also prevalent in certain accounts. However, the role of DMK workers and Tamil teachers in ensuring that the anger became actionable cannot be ignored. In fact, some accounts even go to the extent of stating that the metaphorical “bomb,” which the Madurai incident turned out to be, was strategically put together by the DMK to further their political interests with the support of Tamil teachers who wanted to ensure their own relevance in perpetuity and that the student bodies only “lit” the “bomb,” resulting in the “sparks” that engulfed all of Tamilnadu (“Interview with Pa. Seyaprakasam,” 2008).

A periodic return to the caste and class angle of the narrative becomes inevitable, as it becomes the thrust area during my interview with Mohan Ramiah. A banker-turned English teacher, Ramiah was also a 15-year old resident of Madras (now Chennai) when the Madurai riots took place and was of the view that the riots served as that violent impetus required to forcefully articulate the anxieties of the middle class. “During the agitation in the lead-up to the Republic Day cut-off date in 1965, I remember my elder brother (who was doing his graduation at that time) and his friends speaking only about how getting government jobs would become extremely difficult if the adoption of Hindi sailed through. A couple of them were planning to give their IAS exams the next year and were particularly concerned, as they had not learnt Hindi in school or in college. Mind you, these were all middle-class Brahmin boys. I also remember some of them talking about how the protests, besides giving them long spells of holidays, would show the Congress government in the state and the centre a thing or two about the fierceness of the Tamils, a population that was widely considered to be docile. They, however, never participated in the protests. I clearly recall a friend of my brother talking about how it was best to stay away from trouble, given that those who had been picked up by the police for protesting or demonstrating would find it extremely hard to find jobs once the agitation was over.” (Ramiah, 2012).

The sense that I got during the course of that interview, of this idea that those who protested and those who benefitted were not always the same people, is reflected by other voices as well. Forrester (1966; 23), for instance, states that “students, lawyers, and businessmen, indeed the Madras middle class generally, see their interests as tied to the continuance of English as the language of government and the courts and, more particularly, as the medium for the Union Public Service Commission competitive examination.” Pandian (1996; 3323) approaches the debate from the end of Tamil self-respect and mentions that “in the early Dravidian movement’s engagement, the language issue attempted to break the people-intellectual separation which was affirmed by the Brahmin orthodoxy in Tamil Nadu through Sanskrit, the sacradotal language, and English, the language of colonial governance.” Thus, it is important to acknowledge that the Madurai riots, widely dubbed as an “anti-Hindi” agitation, are also seen as ‘pro-Tamil’ and/or ‘pro-English’ by certain quarters and that the caste and class positions that allow for the synthesis for such opinions are remarkably different from one another needs to be brought forward here.

In order to get a sense of the emotions of those who lived in and around the epicentre of the violence, i.e., Madurai, I also sought out and interviewed noted Tamil writer E. Ra. Murugan Ramaswamy who, at the time of the riots, was about 12 years old and lived in Sivangangai, a neighbouring district that was less than 50 kms away.

Ramaswamy vividly recalled the violence and the impact that it had on him as a child. “The Madurai riots set off a great deal of violence in the areas surrounding it. Sivagangai was also not spared. In fact, the first person to die in a police firing was Rajendran, a student who had graduated from the school that I was studying in. I had seen him a couple of times at school. Apparently, he was shot near Annamalai University in Chidambaram. Ironically, he was the son of a police constable himself. It was a life-changing event for me, as that was the first time someone I knew and had seen (outside of my family) had died. I remember me being very angry. Those were the days when Hindi books and even the parts of the Constitution bearing the language clauses were burnt to register protest. I rushed into the house, pulled out a Hindi guidebook and set it on fire. My mother reprimanded me severely for the act. Later, I learnt that she had been angry because a curfew was in effect and the police had been given shoot-at-site orders.” (Ramaswamy, 2012).

Ramaswamy also recounted a deep sense of dissatisfaction that prevailed amongst those in his district with respect to Chief Minister of Madras at that time, M.Bhaktavatsalam. “In our school, we hated Bhaktavtasalam. The Tamil teachers had told us that he was a sell-out to his Hindi masters at the centre and we believed them. After all, the imposition of Hindi had reached our doorstep as well. For instance, during the Physical Education classes, the command for ‘attention’ and ‘stand-at-ease’ were now hollered in Hindi. I know Hindi today. But at that time, it was completely bizarre. Anyway, if Bhaktavatsalam was the villain, then Karunanidhi was our hero. He was a brilliant orator. Over time, my admiration for Karunanidhi has weaned, given his opportunistic use of the Tamil cause. But the hate for Bhaktavatsalam still lingers.” (Ramaswamy, 2012).

Ramaswamy’s words illustrated, for me, the nature of children’s memories, the deep imprints that incidents of violence and forcefulness leave on them and how the residue of the resentment remains within their system for years. The dismissal of the hero versus villain binary is one that is indulged in routinely. But in the case of Ramaswamy, the Madurai riots and its aftermath, the negative assessments seem to have stood the test of time.

Seeing the spark…

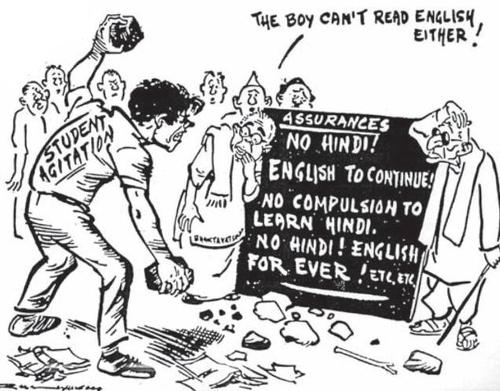

While looking for visual artefacts concerning the Madurai riots, I learnt that this was, for most part, underexplored terrain. Apart from a few pictures accompanying the news reports in English and Tamil newspapers, there was little that I could get my hands on, in terms of a photographic narrative. Even the aforementioned pictures2 were uniform in their depiction, showing large groups of protestors proceeding down the streets bearing anti-Hindi placards and banners3. At the same time, a single cartoon4 by eminent cartoonist R K Laxman became the image of choice whenever the anti-Hindi agitations had to be referenced. The cartoon depicted a young man, representing for the student agitation, pelting stones at a board with English text assuring them that there would be no compulsion to learn Hindi. The then-Chief Minister of Madras, M Bhaktavatsalam, is seen pointing out that the young lad does not know English as well. In June 2012, political parties in Tamilnadu registered their protest against the incorporation of this cartoon in the 12th standard Political Science textbooks published by the National Council for Educational Research & Training (NCERT). The letter written to the Union Minister for Human Resource Development Kapil Sibal stated that the cartoon was a “total distortion of history, hurt the sentiments of the people of Tamilnadu and maligned the Dravidian movement.” (Kolappan, 2012).

A search for films and documentaries focussed on the Madurai riots proved futile. Perhaps, as it has been suggested, the Madurai riots fell out of the purview of filmmakers as it was too contentious to make a film on, at that point in time and too “irrelevant to today’s youth” to be made the focus of a film in this day and age (Ramaswamy, 2012). The one film that makes a passing reference to the anti-Hindi agitations is Mohammed Bin Tughlaq (1971), a socio-political satire movie directed by playwright Cho. Ramaswamy. The title and the character allude to the Sultan of Delhi of the same name in 1300s and his questionable decisions such as those of relocating the capital and introducing different systems of coinage. In the film, Tughlaq (played by Cho. Ramaswamy himself) is seen to be tackling with the language protests in a novel manner, suggesting the introduction of Persian as the national language in order to be impartial to both speakers of Hindi and Tamil. The character then moves to solve other problems, terming the language protests a “forgotten matter.” (Ramaswamy, 1971; translation mine).

The film, however, does something very interesting which most other narratives remain silent on, i.e., the role of women5 in the agitation against the imposition of Hindi. In the sequence showing the playing out of the language protests6 in the streets of Madras, the film showcases an archival clip of young women running on the streets, shouting anti-Hindi slogans (Ramaswamy, 1971). As Thara Bhai (2000; 108) notes, “there were many organizations at various levels for the cause of the anti-Hindi agitation. In most of these organizations, there was no women representation. But in one organization viz. Tamil Kaapu Thondar Padai, A C Mallikamani was an office-bearer. But the role played by Mallikamani is not known.” Women, however, are reported to have a played a major role in the fund-raising activities organized by Dravidian organizations during the protests in Madras post the Madurai riots (Thara Bhai, 2000).

Keeping the spark alive…

The riots that happened in Madurai on the day before Republic Day in 1965 have traditionally been framed in binaries such as Tamil versus Hindi, non-Brahmins versus Brahmins, south India versus north India. Even when such binaries have been eschewed, the narratives have remained largely devoid of the experiential aspect and how that complicates the problem of language significantly. Even if one were to accept the proposition that “the nature and process of socio-ethnic and socio-political integration though not isomorphic are interactional in post-feudal societies,” the memories of the Madurai riots deserve to be kept alive, despite the fact that it is a striking anomaly to the idea of a nation’s socio-ethnic unity being achieved through cultural motivation (Annamalai, 1979). And in furtherance of that position, this essay seeks to provide multiple ‘remembrances’ that go beyond the scope of recorded history.

Bio-note

Sriram Mohan is currently a student of the MA in Media & Cultural Studies programme at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. Born in what was then Madras, Sriram did all his schooling in Chennai and moved to Mumbai to pursue his Bachelors in Mass Media from the University of Mumbai. After graduation, he went on to work for a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and World Bank-funded rural mobile banking project through the advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi. He then moved to Bangalore to work with McCann Erickson on brands like ITC Aashirvaad, Britannia & Intel. Soon after, he joined YourStory.in, an online platform for startups & entrepreneurs, where he co-authored the Tech30 Report, a research study that was written about in many leading dailies including the Wall Street Journal. He is interested in technology, education, clean energy, politics, history, news media, cinema, design & poetry.

Appendix:

1. Front page of the Tamil magazine Kudiyarasu (run by Periyar) dated 03 September 1939. Shown below is an editorial titled “Veezhga Indhi” (Down with Hindi) written as part of the anti-Hindi agitations of 1937-40.

2. Anti-Hindi protests in Madras (Image courtesy: The Hindu)

3. Student rally in Madras against Hindi imposition (Image courtesy: The Hindu)

4. Cartoon by R K Laxman depicting the anti-Hindi agitation in Madras.

5. Women protestors shouting anti-Hindi slogans [scene from Mohammed Bin Tughlaq (1971)]

6. Trains defaced with anti-Hindi slogans [scene from Mohammed Bin Tughlaq (1971)]

Interviews:

Name: Ramnad Ramanathan

Occupation: Entrepreneur

Age: 62

Name: Mohan Ramiah

Occupation: Language Coach

Age: 60

Name: E. Ra. Murugan Ramaswamy

Occupation: Writer

Age: 59

References:

Amin, Shahid (1998). Event, Metaphor, Memory: Chauri Chaura, New Delhi: Penguin. p. xiv

Annamalai, E (1979). “Language Movements Against Hindi as An Official Language.” Language Movements in India. Central Institute of Indian Languages.

“Anti Hindi Mobs Raid Home Where President Was Born” (1965, February 16). The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2012 from http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F70F13F93F5812738DDDAF0994DA405B858AF1D3

Butalia, Urvashi (1995). The Other Side of Silence, New Delhi: Penguin. p.7.

Forrester, Duncan B. (1966). “The Madras Anti-Hindi Agitation, 1965: Political Protest and its Effects on Language Policy in India.” Pacific Affairs 39 (½). University of British Columbia. pp.19-36

Guha, Ramachandra (2005, January 16). “Hindi against India.” The Hindu. Retrieved September 24, 2012 from http://www.hindu.com/mag/2005/01/16/stories/2005011600260300.htm

Guha, Ramachandra. (2008). “The Rise of Populism: War & Succession.” India after Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy. London :Harper Perennial. p.391.

Gunasekaran, M (2009, May 15). “At nearly 81%, Karur turnout is highest.” The Times of India. Retrieved September 28, 2012 from http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2009-05-15/chennai/28187702_1_higher-turnout-voting-percentage-m-thambidurai

Hardgrave, Robert L. (1965). “The Riots in Tamilnad: Problems and Prospects of India’s Language Crisis”. Asian Survey 5 (8): 399 – 407.

“India: Retreat to English” (1965, March 5). TIME Magazine. Retrieved September 21, 2012 from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,839301,00.html

“India: The Force of Words” (1965, February 19). TIME Magazine. Retrieved September 21, 2012 from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,940936,00.html

“Interview with Pa. Seyaprakasam” (2008, October). Kalachuvadu Magazine. Kalachuvadu Publishers. Retrieved September 20, 2012 from http://www.kalachuvadu.com/issue-106/page32.asp (translation by author).

Kodanda Rao, Pandu Rangi (1969). Language issue in the Indian Constituent Assembly: 1946-1950: rational support for English and non-rational support for Hindi. International Book House. pp. 44–46.

Kolappan, B (2012, June 9). “NCERT textbook cartoon stokes anger in Tamilnadu.” The Hindu. Retrived September 20, 2012 from http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/article3506029.ece

“Madras Youths Again Stage Violent Anti-Hindi Protests” (1965, February 10). The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2012 from http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F30C17F83F5812738DDDA90994DA405B858AF1D3

More, J.B.P (1997). Political Evolution of Muslims in Tamil Nadu and Madras 1930–1947. Orient Blackswan. pp.156 – 159.

Pandian, M.S.S (1996). “Towards National-Popular: Notes on Self-Respecters’ Tamil.” Economic and Political Weekly. 31 (51): 3323-3329

Ramaswamy, Cho (Director). (1971). Mohammed Bin Tughlaq [Motion Picture].

Simpson, Andrew (2007). Language and national identity in Asia. Oxford University Press. p.71.

Sundararajan, Saroja (1989). March to freedom in Madras Presidency, 1916–1947. Lalitha Publications. p.546.

Thara Bhai, L (2000). Women’s Studies in India. New Delhi: APH Publishing Corporation. p.108.

Interviews:

Ramanathan, Ramnad (2012, September 18). (S.Mohan, Interviewer).

Ramaswamy, Murugan. E. Ra. (2012, September 19). (S.Mohan, Interviewer).

Ramiah, Mohan (2012, September 24). (S.Mohan, Interviewer).

1 See “Appendix” for related photograph.

2 See “Appendix” for related photograph.

3 Ibid.

4Ibid.

5 See “Appendix” for related photograph.

6 Ibid.