Humour as the Weapon of the Weak: A Reflection on Comics at the Grassroots

Rajeswari Saha

ABSTRACT

This paper is based on the author’s empirical research and field practice on comics as a community media that has been used by marginalised communities in certain parts of India, where the medium of self-expression was owned and made by community, the motive of which was to bring forward the self-expression and personal narratives of the creators. This paper focuses on comics that are developed, circulated, and taught by common people rather than artists or mainstream comics creators, to promote social movements that raised the hope of changing the comics scenario in India. It highlights the intent and phenomenon of grassroots comics along with other parallel comics movements in India.

The visual “text” of the characters in the earlier mainstream comics created a hegemony over the indigenous voices of the country, separating the media from the local people and made it even worse by not attempting to represent the grassroots realities. It is in this context that one needs to understand the emergence of alternative forms of comics that were written to address social realities, gave rise to social movements across the country, and brought forth stories from unknown corners of India. This paper addresses the role of comics as a powerful grassroots voice and the conflicts faced in the creating the comics in the otherwise hegemonic spaces dominated by popular media Keywords:

KEYWORDS

Comics, grassroots, development communication, social movements.

INTRODUCTION TO COMICS

“The cartoon is a vacuum into which our identity and awareness are pulled … an empty shell that we inhabit which enables us to travel in another realm.”

McCloud (1993: 36)

In Understanding Comics (1993), Scott McCloud speaks of comics but refers to them as cartoons because for him, to distinguish between cartoons and comics would take as much time as discussing just comics. So, for simplicity’s sake, he uses the term “cartoon” to encompass comics. As Meskin (2007) problematised the definitions of comics in his article “Defining Comics”, he echoes the definitions of McCloud, Greg Hayman, and Henry Patt in which comics are juxtaposed pictorial narratives either by themselves or corroborated by text. Meskin (2007) points out that these definitions are too broad but unarguably re-establishes that a comic is, by and large, sequential art. Having read and understood comics through McCloud, I would also like to point out that the most interesting point of comics is the space between each panel, which is referred to as the “gutter space” by him. Comics give one the liberty to touch, feel, and imagine the images laid out in a sequence and all at once. Within this understanding, the space between the panels of the comics triggers one’s imagination; I regard this as the strongest distinctive feature of comics.

Crutcher (2011) considers comics as representations of imaginations, unlike photographs, as they are drawn. So, unlike film or photography, which have “intrinsic” pretensions to accuracy, comics are “volatile”. They move beyond place, could be real or imagined, and are transformed through someone’s eyes and hands. Crutcher (2011) further adds that a transposition of roles occurs in the production of comics; the role of an author, voiceover artist, action, drama director, etc., is equivalent to any scriptwriter, director, or editor. Hence, the approach of comics is collaborative and in a narrative form that gives an image to the viewer to understand the locale. The text in the dialogue box corroborates the events and adds more context to the seeing, allowing space for the creator as well reader to interpret realities. The most important aspect of comics is that they contest the notion of good drawing and emphasise on the text or the content. It shows a fraction of information—as much as is required to make sense of the narrative. It includes a deep process of recalling, reproducing, and illustrating the imagined (Crutcher 2011; Risner 2011). Comics came to India rather late, though there are early precursors to the idea of comics in the ancient traditional picture stories of India.

THE HISTORY OF COMICS

India has been traditionally a hub of visual storytelling and has seen the transition from cave to mural to paper scroll paintings over a period of time. Visual stories or chitrakatha can be seen in traditional sequential art and performance art such as Patachitra in West Bengal, Gond in Madhya Pradesh, Chitrakathi in Maharashtra, Phad in Rajasthan, Cheriyal scrolls in Telangana region, and so forth. These traditions of scroll paintings are recorded to be centuries old; some were as old as 2,500 years. The narrative scrolls followed a sequence of being painted either in a horizontal format or vertical format. As the chitrakars or artists unrolled the long scrolls, stories were sung in front of the audience. One can easily identify the presence of a comics culture in the age-old tradition of drawing on scrolls, but unlike comics, the text or narratives were usually sung as a tradition in India (Lent 2015).

Comics are a form of sequential art and, since Indian artists had been acquainted with traditional forms for a long time, they soon adapted to the popular “text” of comics. Hasan (2007) identifies the earliest comic in India being published in Oudh Punch (also Avadh Punch) based in Lucknow, which began in early 1854 and continued till 1956, and Delhi Sketchbook between 1850 and 1857. Avadh Punch was an Indian version of the popular political cartoon magazine Punch of England that started in 1841. There were many regional versions—Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, Gujarati, and English—that were produced between 1877 and 1956 by different artists. By 1910, versions of Punch were published in Oudh or Avadh itself (Khanduri 2014). Since this comic weekly was published during the colonial period in India, it used comics to create satire about the British Empire.

Menon (2017) notes the evolution of comics in India since 1926 till the contemporary times. She establishes the initial period of the rise of comics as the pre-1950s era, which engendered children’s comics such as Balaak (established in the year 1926 and published till 1986), Honhar, and Chandamama (monthly children magazine, started in the year 1947, illustrated and edited by Kodavantiganti Kutumbarao, an exponent of Telugu literature). Chandamama was acquired by the Mumbai-based software company Geodesic Information Systems in 2007 and continues to come out in digitised versions in different regional languages. It was this era that started the children’s comics adapted in a third-person narrative or rather in a fashion in which grandparents narrated stories to children, also ascertaining the fact that comics were meant for children. It was between late 1950s and 1960s when the Indian version of international superhero comics, such as Phantom, Mandrake, Flash Gordon, and Rip Kirby, came into being, starting the trend of regular syndicated comics strip in India.

The 1960s kicked off the golden era of Indian comics with the advent of Indrajal Comics in 1964, which was launched by the publisher of The Times of India—Bennett, Coleman & Co. This series introduced foreign superhero comics of Phantom, Flash Gordon, Mandrake and so forth to the Indian audience. These comics were so popular in the Indian market that a need was felt to introduce an Indian character as well, to whom the Indian readership could relate. Therefore, in 1976, the character “Bahadur”, illustrated by Abid Surti, was born and his stories focused on dacoity that was on the rise in India during the 1970s.

This golden era also saw the advent of Amar Chitrakatha by Anant Pai 1967, which narrated myths, folktales, and epics from India. The year 1969 saw the birth of Chacha Chowdhury, created by Pran Kumar Sharma, which resonated with the emotions, wit, and humour of a common middle-class man. It was in the year 1980 that Tinkle, a fortnightly magazine, brought characters like Suppandi, Shikhari Shambu, and Ramu and Shamu to Indian readership. It was initially introduced in English but, within no time, it was translated in to various Indian regional languages, including Malayalam, Hindi, and Assamese. In 1986, Raj comics brought more superhero content to the Indian readership with characters like Supercommando Dhruv, Nagraj, Parmanu, Bhokal, Shakti, and so on. It is at the same time that the comic Detective Moochwala, illustrated by Ajit Ninan, appeared in Target magazine, a part of the India Today Group. Target also published illustrations by the first female Indian cartoonist Manjula Padmanabhan (Kannan 2004; Khanduri 2010; Kumar 2003).

Traditionally speaking, comics are juxtaposed pictorial narratives that can exist either by themselves or in corroboration with texts. Every line art made after Amar Chitrakatha in the 1960s was either used for political lampooning or creating mythological narratives. The common comics made for all by the mainstream players were not very successfully in engaging with all kinds of readership; they did not represent the diversity of cultures that constitute rural India. Moreover, the common person was still missing from comics. Even political artist R.K. Laxman’s syndicated comics strips in the Times of India that portrayed the “common man” had the trappings of the educated, sophisticated man who would be able to read and write, who would understand literature, and could debate politics. There was always a common vantage point from which the mainstream comics looked at the audience.

Comics have been instrumental in bringing developments in the social sector to the public. Comics were introduced in educational textbooks, newspapers, posters, and graphic novels using folk and indigenous art forms, and these experiments had been successful in keeping intact the readership of different age groups (Kannan 2004). The focus was on mythological stories at first, followed by superhero comics; there was a dearth of comics that were made on “grassroots” stories. It was this realisation that built a community around the growth of an alternative comics culture in India that portrayed people’s problems and social realities; I am speaking of cartoonists such as Orijit Sen with his graphic novel River of Stories (1994) and Sarnath Banerjee with his graphic novel Corridor (2004). They introduced local realities and common people’s stories to mainstream print. River of Stories outlined the environmental issues surrounding the river Narmada and is perhaps a landmark in the history of the Indian graphic novel.

THE MAINSTREAM COMICS

Saima Saeed (2009) reflects on the power the mainstream media has and the way it not only suppresses the flow of information and facts but also mutes the consciousness of people. The option of 100 channels that the cable TV gives us nowadays mutes the critical thinking of human beings, entertains them, and puts them to sleep after a busy schedule of a regular, mundane work life; it does not rattle their conscience, which does not make noise even when their rights are under threat. The viewer again skips channels and puts his/her conscience to sleep.

As mentioned earlier, in the case of mainstream comics, the component of local people and their contexts was still missing in these comics for a long time. This medium of expression did not convey thoughts and ideas of people from the grassroots. The whole concept of local people expressing their ideas through comics is that the person is not producing the piece of art because of any commercial agenda but simply because s/he never had access to this media before and would like to use it to voice her/his concerns. In the process of creating grassroots comics, people get to know how to write their personalised stories in panels (four parts) based on their lived and learnt reality/realities. The story thus is a more grounded representation of the community. This paved way for individuals to communicate, breaking the traditional norms to approach comics as a medium for professionals only to communicate their ideas. During the early 2000s, the idea of grassroots comics came to Sharad Sharma of World Comics India (WCI), and with a bunch of like-minded people, the “wallposter” comics idea was generated by him (Walia 2012). The WCI has been instrumental in forming networks with other implementing agencies that continue to spread the idea of grassroots comics globally through grassroots comics campaigns in order to promote self-expression and first voices of the local people. Such campaigns usually evolve after a series of comics are made by the local people, using local culture and local languages, reflecting certain issues within their lives. The entire process of the campaigns is participative at every step, especially because the people who prepare the campaign material usually get help from their families, friends, and colleagues. While the WCI has been revolutionary in bringing the first ever grassroots comics in India, there are also other individuals and agencies who contested the stereotypical representations in mainstream comics.

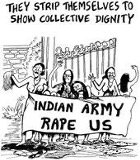

The founder of the WCI, Sharad Sharma, along with Rahul Pandita came up with an underground comics on the Manipur social movement “Meira Paibi” in the early 2000s. The 24-page comic booklet was pocket sized and contained incidents and struggles of women protesting against the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) signed in 1958.

Figure 1.1: “Drawing on Experience” Source: The Telegraph (2004), 26 December. Available from: https://www.telegraphindia.com/culture/style/drawing-on-experience/cid/1549640 [Accessed: 8 May 2021].

Ram Puniyani also speaks about how introducing comics into the Indian context of educational books, history, and literature has changed the reading scenario. His book Communalism Explained: A Graphic Account, jointly edited by him and illustrated by cartoonist Sharad Sharma of the WCI, gives an understanding of communalism and terrorism in a question-and-answer comic form. Comics have been used internationally to break complex social theories into visual texts for the social masses, especially students. For instance, in the 1960s, we have the political cartoon books of Eduardo Humberto del Río García, who used the popular pen name Rius to explain Karl Marx’s theories and advocated for the Cuban revolution. The most popular amongst the books was Marx for Beginners, published in 1972; it marked a similar revolution in education through comics throughout Cuba. Inspired by Rius, the Beginner series was adapted by Icon Books from 1992 to explain critical social theories. Rius brought into comics culture a critical visual intervention rather than regarding comics as entertainment or humour meant for children. Recently, a new comic by Sumit Kumar, Amar Bari Tomar Bari Naxalbari, narrates the story of Naxalism in West Bengal and the historical and political conflict from 1970s till date. The story is a satire on Naxalbari and the government(s) in power.

In the recent past, the Indian traditional painting forms have been used to narrate stories through comics. The contemporary graphic novel Bhimayana: Incidents in the Life of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar has used Gond art and text to narrate the story of B.R. Ambedkar and the social events in the life of Dalits in India. The main purpose of the book was to bring forward B.R. Ambedkar’s story to the mainstream graphics industry which otherwise is spoken about in political and/or academic discussion(s) (Jenkins 2015).

Figure 1.2 Page from ‘Bhimayana’, story of B.R Ambedkar through Gond folk form. Source: Jenkins (2015).

The illustrators Aarti Parthsarathi and Chaitanya Krishnan use Indian miniature paintings from various sources and narrate socio-political stories in their weekly webcomic series Royal Existentials (www.royalexistentials.com). The Indian miniature paintings are perhaps thousands of years old but the series is refracted through issues of gender, social norms, and political issues of the present times (Narayanan 2014).

Priya’s Shakti written by Ram Devineni and Vikas K. Menon and illustrated by Dan is a reality inspired comic book on the Delhi rape case of 2012 that narrates the story of Priya, the protagonist, an ardent follower of goddess Parvati and a sexual assault survivor who wants justice by working for the cause of women rights. She seeks blessing and power from Goddess Parvati to fulfil her cause.

Figure 1.3 A page from ‘Priya’s Shakti’ graphic narrative. Source: https://issuu.com/rattapallax/docs/comicbook; accessed 25 February 2021.

The illustrators later came up with augmented reality filters in association with the tech organisation Blippars to bring out an app that can communicate with larger audiences and makes the comic more collaborative. Various street art and exhibitions were organised in the cities of Mumbai, Bangalore, and Delhi for better outreach of stories. Their next story, Priya’s Mirror, deals with acid attack and is based on the real accounts of the survivors; this comic, too, deals with gender-based violence in India.

The Menstruepedia Comic was developed initially as a crowdfunded project by Aditi Gupta, a former student of National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, and her husband Tuhin Paul in 2012. The comic revolves around four characters—Pinki, Jiya, Mira, and Priya—each playing a significant role in telling the story from puberty and first days of having periods to consulting a doctor, each character portraying the nuances of adolescence and menstruation in the simplest way possible. The artists felt that there was a need to portray stories and people that every corner of the country could relate to. They have successfully adapted the comics in to 10 diverse languages, including Spanish and Nepali, with an outreach of over 75 schools and 50,000 girls living in the rural India. The aim of the artists was that the easy availability of these comics on the web and in print on school bookshelves would ease the initial inhibitions over reading about menstruation and raise consciousness of it (Sahariah 2016).

COMICS AS A COLLABORATIVE COMMUNICATION MEDIUM

When two people communicate, the medium of communication plays an important role, and if that medium is made by the people themselves and not a third source, the language of communication takes a leap and is able to narrate thousands of first voices rather than dominant stereotypes (Chute 2006). Communication here calls for a horizontal approach that encourages a dialogue centred on issues concerning a particular community and a bottoms-up approach that is aimed at raising the consciousness of the decision makers (Otsyina and Rosenberg 1997). The meaning of comics transformed slowly over time, in this the point to be stressed is to discuss “who is the creator” and “what is being created”. When one looks at the comics’ journey in the mainstream media, one can initially identify comics being used as syndicated strips in corners of print magazines and newspapers and to communicate children’s stories. One can also notice the creator being a trained artist creating a satirical strip in a mainstream newspaper having their policies and guidelines in place. But imagine when comics are created by people who are not artists but simply using it as means to express their concerns over developmental issues that concern them directly. This places comics as an alternative voice of the oppressed amidst the popular mainstream media, and a community media in this context. In the study, while relating to grassroots communication, many dimensions of comics are focused upon factors such as local cultures, social contexts, and relationships in the community. The old traditional visual storytelling forms that I spoke about earlier had a culture that was shared and passed on from generation to another; the ways of living were shared through these sequential scroll paintings as well. But the moment it was used as a medium for development, the language of the visual text changed, and that is the same with comics. Whether they are popular, drawn comics or traditional art forms transformed into comics, there is a stark difference between being used as a medium for communicating pre-determined messages and being an organic, culturally located art.

Development communication (devcom) now includes participatory action for learning and sharing of power within the social contexts (Srampickal 2006), leading to the emergence of grassroots communication. Hence, in this context, the communication for development processes facilitates a dialogue where power is shared. It is this meaning of devcom that I invoke in my use of the term “grassroots communication”. It includes the complete involvement of the local people that affirms democratisation within the specific cultural context. Grassroots communication gives weightage to local people’s aspirations and is located in the community culture as it entertains and reifies the same cultural values.

Communication here is understood to link individuals, communities, governments, and citizens through participatory and shared decision-making. Communication media that are owned by the community support the development process through a focus on changing attitudes and initiating a positive dialogue within the community. Development initiatives that begin with communities and organisation(s) refer to social actors participating in social movements that challenge power hierarchies to reach a greater autonomous, self-reliant, and locally owned, independent systems of communication (Servaes [1989], as cited in Srampickal [2006]). In order to achieve this goal, every unit of development process will have its own particular trajectory leading to multiple paths of development, which should primarily define development in cultural terms rather than economic or political terms.

The grassroots communication for development, or what we generally call “devcom” comics, uses this aspect of relationship of the media with the individual who creates it; the medium gives importance to the participation of the local people in creating, narrating, and sharing the skill and, hence, they are termed as being the “first voice” of the community (Packalen and Sharma 2007). Comics can be with or without words; there are comics where the text is absent but still the comics become powerful because of two primary elements: the panels and the quality of putting “as much required text” in the storyboard (Crutcher 2011; Risner 2011). Here the objects represented in the comics, the textures used in the drawing becomes self-representative of the narrative, something left to the audience to decipher. The alternate comics that intend to bring out lived realities such as Priya’s Shakti or the grassroots comics approach of the WCI bring these first voices to a large readership. These comics might not be much spoken about but are not ignored.

RIPPLE EFFECT: GRASSROOTS COMICS AS SOCIAL MOVEMENT MEDIUM

In the recent past, it has become important for implementing agencies to address social concerns through visual media. These visual media, such as posters, television commercials, radio, print newspapers, theatre, and comics, when created by a mainstream artist, tend to be located in a top-down approach of communication; they do not generate a dialogue because of the difference in language, humour, and visual text. The difference in visual text meant that the dress, behaviour, language spoken, and humour prevalent within the community that needed to be addressed was unlike the posters and other visual media that were generated by the mainstream artist. The participation of the community became important in the media and, hence, the success of community media is growing and helping address social concerns. Apart from other interesting community media, such as community radio, community newspapers, community theatre, community video, and so forth, community comics served as the most efficient and cost-effective medium for the organisation Plan India in an internal survey of 2008–9. Plan India (2008–9) had used comics to generate stories of adolescent children between 10–16 years on corporal punishment and sexual abuse in different parts of Bihar, and replicated the same in other neighbouring states through visual stories that are actually inspired by their lived experiences.

My study on grassroots comics in the years 2009–11 brings forward interesting highlights of comics when used as a devcom medium. The study was based on children working with the organisations Adithi/Plan in Muzaffarpur and the WCI in Delhi. I used a descriptive research design and qualitative research methods to analyse the data. The research initially began in Muzaffarpur, but there were two other districts as well, Sitamarhi and Vaishali, where I found the impact of the medium, with families taking part in the comic-making process. The WCI had conducted workshops in the organisation Adithi/Plan[i] in Muzaffarpur with children, who were beneficiaries of Adithi/Plan. These children took part in the comic workshop along other devcom workshops, and started responding quicker to comics than other media such as community theatre, community radio, community newspaper, etc. Hence, comics were later used by the parent organisation to address local governance issues which otherwise could not be addressed through posters and other mainstream media in the community.

THE CAMPAIGN

In 2003, “Diya Puta Manch” (DPM) was set up by Adithi/Plan in Muzaffarpur, where both girls and boys would participate equally in campaigns pertaining to healthcare, education, etc., the funders and the organisers, after reviewing the outcomes of the fieldwork, saw that communities did not develop the thought process to give importance to a child’s viewpoint. Keeping all this in mind, two things cropped up: first was that the elders in the community thought that the Adithi/Plan was trying to make children rebellious; and second was that the children felt that somehow they were not able to utilise their full creative potential, as a result of which the child club—DPM—was difficult to sustain. For the funders it was always necessary to forward the voices of the children in the community. Also, the organisers are seen as outsiders in the community. Hence, the first step was to include a personality development[ii] training programme for children, where inclusive forms of media were used. This generated massive participation from the community and, in turn, boosted the confidence of the children. Adithi then initiated the “Nikhar Project” to provide a platform to children where they could discuss their issues with panchayat raj institution (PRI) members, ward members, and block-level government officials. They had over 45 children clubs operational and identified 25 more with whom they decided to work. Issues related to child protection and child rights were discussed in meetings of these child clubs. The project implementers and the children articulated that children took out a drive on “Jan Panjikaran” (public registration) in their community and as a group and collected 672 responses from the survey. They conducted this drive because they realised that many children in the community could not take admission in schools as they did not have any identity proof. Most of the respondents shared that if elders in the community were not addressing these issues of child rights, at least someone has to, then why not the children. So, discussions were carried out to regularise child club meetings. Subsequent meetings were followed with the PRI members and block-level governing officials to discuss local governance issues.

One of the objectives of the Nikhar Project was to increase the interaction between the community children and the panchayat. When the block-level campaign was organised in Kanti (city in Bihar, India), the Mukhiya (head) addressed the issues of corporal punishment and birth registration. He called for a meeting with the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM), Aanganwadi workers, and the Adithi/Plan to discuss the issue of birth registration and ways to promote it. He also visited the schools to evaluate the situation. The Block Development Officers showed interest in seeing the children and suggested putting up a campaign for 33 district development commissioners who were coming to Kanti. The campaign was put into action and got support from various local mainstream media. When the Nikhar Project, the initial project that trained all children in diverse community media, was launched, Adithi’s objective was to provide a platform to the children and equip them with media tools so that they can voice their opinion(s). The next stage was to see the reaction of the people towards these tools.

The children were exposed to various forms of community media for many years by now and even with comics the journey from creating a story and expressing it in wallposter comics was a smooth one. Children used comics as a medium to express and disseminate information in the campaign, which was named “Ab Shasan Humro Hoi” (“It’s Our Rule Now”). The workshops that were initially conducted by the WCI lasted five days, where basic skills were imparted, and at each step of the workshop, children learned to draw. In this process, basic stick figure drawings and facial expressions using OT[iii] technique was imparted to the children. For instance:

Figure 1.4 Facial expressions using alphabet O and T Source: World Comics India Comics Manual handbook Page 13 https://www.worldcomicsindia.com/Manuals/BASIC_MANUAL_Eng.pdf

Following the drawing exercise, children were taught how to write a story, break that into a story board and then the final comics making process took place. First, the stories were pencil drawn in four panels on two A4 sheets pasted horizontally to make an A2 wallposter comics. Then, black ink was used to trace the drawings, and finally, the pencil marks were erased and final copies were photocopied at the nearest shops. The resources used were planned keeping in mind that pencils, A4 sheets, pens, rulers, erasers, and photocopy shops can be found in every part of rural India. The last day consisted of a field trip, which brought out the exact reason the workshop was conducted with the children in the first place. The field trip indicated that the final comics were to be shown to their own community people, pasted on community notice boards, schools, trees, and lamp posts for the community to react to and share their feedback. That process was what made the medium of comics more collaborative than used in print mainstream.

Figure 1.5: A comic made during the Campaign “Ab Shasan Humro Hoi” in 2009

The interesting part of a grassroots comics movement is that it gave a first-hand exposure to children, in this case, particularly regarding thinking critically about their social environment, enabling them to take part in social action. The previous campaigns by the WCI on sexual abuse, corporal punishment, and local governance in different states had a ripple effect in the neighbouring rural areas. Reproducibility of grassroots comics made it convenient to make voices heard. The comics were replicated and more and more people were drawn into the campaign because an otherwise-serious and sensitive topic was handled with much ease and humour. The replication of comics was also an easy and cost-effective process, which again makes it an ideal community medium. At a larger level of the community, the pattern of participation involves communication strategies instilled in the process of developing the community and balancing the relationship. The kind of horizontal communication that was exhibited in the process was moving from an initial focus of informing and persuading people to change their behaviour or attitudes to facilitating exchanges between different stakeholders to address the common problem of good governance. The children developed the skill, and shared the idea of what they found as innovative communication with their parents; the parents and the siblings naturally became recipients of the information and the communication process. This evoked interest in other communities (at locations like Kanti, Aghoria Bazar, Bochaha, Katra, and Sikanderpur) participating in a process where the production and outcome are controlled by the children. Receiving responses and the power to be heard in their own neighbourhood gave a sense of ownership within the community for the children. This led to a common development initiative with the local panchayat and block officials to experiment with possible solutions and to identify what is needed to support the initiative in terms of partnerships with the local or block officials besides knowledge and material dissemination.

The children took part in a process like this because they loved making comics, their families took part in this because their children made the comics, and finally their neighbours took part in it because the stories made were relatable. The narratives built were not of Super Commando Dhruva (character in Raj comics) but of their own village boys and girls. The children’s participation drew some attention from their parents and they slowly liked the idea that they were doing something serious but through comics. They were glad that the children were eager to read newspapers and books and adapt themselves to make better comics. In comics as well, “content is the king”. The better the content, the better the readability and the greater the interest of children of these communities in relevant content. They knew that fine drawing was not necessary; they wanted to speak, even if through “stick figures”.

CONCLUSION

As I speak of comics evoking humour at the grassroots level and effectively carrying out a successful campaign in a rural setting, I am talking about a place that did not have any access to mainstream media. It is very recently that my research site got access to television and radio. It upsets me to think about comics and artists targeted for commenting on the state of affairs or simply because they are making comics on political events. On social media and within the mostly developed urban society, the consumption of comics or satire has started to offend people, and slowly, the use of comics has created uproar without having the sensibility to maturely debate. The use of humour and satire, particularly on the Internet, in comics, by stand-up comedians, or videos on socio-political and religious issues or celebrities, has begun to offend sections of urban classes. What was once understood as satire is seen with intolerance as “anti-national” for many common people living in the metropolis. The rise of religious fundamentalism in the current era of right-wing governments in India and elsewhere has resulted in intolerant and sometimes violent reactions to humour and satire. In the Indian context, nationalism has taken on hard connotations, tied up with Hindu gods and mythical symbols, such as the cow, which cannot be questioned or made fun of. The emergence of a politics of hate, involving the othering of minorities and those who think differently, and demanding rigid observance of certain rituals of nationalism have led to a decline in openness to engaging with humour.

Further, there have been a few instances of comics and comedians enraging “nationalist” sentiments. In 2012, Aseem Trivedi, a political cartoonist, was arrested for mocking the Constitution (Ghosh 2012). In 2016, the political group Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) filed a FIR against comedian Tanmay Bhatt of the popular comedy group All India Bakchod (AIB) for posting a Snapchat of face swap between Lata Mangeshkar, an Indian playback singer, and Sachin Tendulkar who was once an ace player in the Indian cricket team. The MNS felt that the national icons were made fun of and disrespected (Bose 2016). In 2017, Nituparna Rajbonshi received a death threat for linking the Gorakhpur tragedy with the current government. In his cartoon, he had talked about the rise in crime against women and farmer suicides and very recently in 2021 a popular stand-up comedian named Munawar Iqbal Faruqui got arrested for a joke he never uttered yet misunderstood by organisers and audience (Faleiro 2021). Comics have the audacity to talk about big issues through minimalist concrete messages and, without doubt, give the scope to people to understand and appreciate humour and satire. The medium of comics has been largely experimental. Apart from superhero comics, there have been newer underground comics, comics on war, and comics with the women as central characters. Along with its many elements, it still remains an active generator of satire in the genre of visual literature.

I have always been fascinated with comics because they gave me the ability to imagine more visually than reading plain text does. The panel boxes were an interesting space to watch for. The panels show the images that are required to narrate the story, anything that is not required or seems aesthetic is not portrayed in a comic panel. The journey from one panel to the other is the most spectacular one, and that makes comics a very interesting medium. As we understand noise in communication, gutter-box represents that noise, created to make the audience extremely imaginative. The gutter space is a particularly interesting feature: one can kill or give birth in this space—it is right in front of the viewer, giving time to jump between sequences, to think what would happen next. Such is the imaginative power that is elicited by comics.

The alternative form of comics that is undertaken by many artists in India, which I have already discussed, have powerful content but are still not accessible to the general masses who cannot read and write in English or who cannot understand the kind of humour in those comics. I feel the alternative comics are created for a bunch of elite readers; right now, the developmental approach is fully missing. However, this demand is slowly being fulfilled by the WCI. The more the idea of community comics reaches the corners of the marginalised communities, the better the understanding of comics as a “weapon of the weak” can be established. The grassroots comics idea of the WCI establishes one such start to affirm that the self-expression of the community is of paramount importance. Though a medium such as comics is reproducible, easily learned, adapted, and recreated, it is unfortunately not being used to the fullest extent for facilitating horizontal communication and development. Perhaps it will take some more years to have artists in every corner of rural India using comics and creating their own augmented reality versions of it, which can only be possible if the medium reaches those living in the marginalised communities.

Dr Rajeswari Saha is Assistant Professor of Media and Communication with International School of Business and Media, Pune. She was a doctoral student with the School of Media and Cultural Studies at TISS, Mumbai, where her ethnographic study was focused on exploring the nuances of art and its context within the scroll performing community of Naya village in West Bengal. She has been a comics trainer and practitioner for the last thirteen years. She has previously conducted an MPhil research based on discussing comics as community campaign medium with children as social actors addressing local governance in a community of Bihar. Her interest lies in the study of gender in folk performances and popular culture.

REFERENCES

Banerjee, Sarnath (2004) Corridor. Penguin.

Bose, Adrija (2016) “Dear PM Modi, It’s Not Just You, We Are All Scared of Cracking Jokes,” Huffington [Online], 28th June. Available from: http://www.huffingtonpost.in/2016/06/28/modi-arnab-joke_n_10709738.html [Accessed: 25th February 2021].

Chute, Hillary L. (2006) Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. Columbia University Press.

Crutcher, P. (2011) “Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry through Bestselling Batman Stories”, The Journal of Popular Culture. 44(1): 53–72.

Faleiro, Sonia 2021. “How an Indian Stand Up Comic Found Himself Arrested for a Joke He Didn’t Tell”, 10th February. www.time.com. Available from https://time.com/5938047/munawar-iqbal-faruqui-comedian-india/ [Accessed: 25th February 2021].

Ghosh, Shamik (2010). “Outrage over Cartoonist Aseem Trivedi’s Arrest on Sedition Charges for ‘Mocking the Constitution’”, 10 September. www.ndtv.com. Available from: http://www.ndtv.com/india-news/outrage-over-cartoonist-aseem-trivedis-arrest-on-sedition-charges-for-mocking-the-constitution-498901 [Accessed: 31st January 2021].

Hasan, Mushirul (2007) Wit and Humour in Colonial North India. New Delhi: Niyogi Books.

Jenkins, Henry (2015) “In Search of Indian Comics (Part One): Folk Roots and Traditions”, 25 November. www.henryjenkins.org. Available from: http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2015/11/in-search-of-indian-comics-part-one-folk-roots-and-traditions.html [Accessed: 31st January 2021].

Kannan, K. (2004) Comics for All (CFA) [Newsletter]. Delhi: World Comics India.

Khanduri, Ritu Gairola (2010) “Comicology: Comic Books as Culture in India”, Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 1(2): 171–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2010.528641.

Khanduri, Ritu Gairola (2014) “Colonial Times”. In: Kanduri, R.G. (ed.). Caricaturing Culture in India. Cartoons and History in the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pg. 44–118.

Kumar, Manas (2003) Today’s Comics Culture in India. Asian Pacific Cultural Centre.

Lent, John A. (2015) Asian Comics. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

McCloud, Scott (1993) Understanding Comics. Northampton, MA: Tundra Publishing.

Menon, Mandovi (2017) “A Complete Timeline: The Evolution of Comics in India (1926–Present)”, 13 March. www.homegrown.co.in. Available from: https://homegrown.co.in/article/21898/a-complete-timeline-the-evolution-of-comic-books-in-india-1926-present [Accessed: 31st January 2021].

Narayanan, Nayantara (2014) “A New Comic Strip Uses Mughal Miniatures to Convey Contemporary Angst”, Scroll, 17 November. Available from: http://scroll.in/article/689952/a-comic-strip-uses-mughal-miniatures-to-convey-contemporary-angst [Accessed: 31st January 2021].

Otsyina, J.A. and Rosenberg, D.B. (1997) “Participation and the Communication of Development Information: A Review and Reappraisal”, Information Development 13(2): 89–93.

Packalen, F. and Sharma, S. (2007) Grassroots Comics: A Development Communication Tool. Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland.

Plan India (2008–9) Annual Report 2008–2009.

Puniyani, Ram and Sharma, Sharad (2011) Communalism Explained: A Graphic Account. New Delhi: Vani Prakashan.

Risner, Jonathan (2011) “‘Authentic’ Latinao/os and Queer Characters in Mainstream and Alternative Comics”. In: Aldama, F.L. (ed.). Multicultural Comics: From Zap to Blue Beetle. Austin: University of Texas. pg. 39–54.

Saeed, Saima (2009) “Negotiating Power: Community Media, Democracy, and the Public Sphere”, Development in Practice. 19(4–5): 466–78. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09614520902866314.

Sahariah, S. (2016) “The Indian Comic Book That’s Taking on the Taboo of Periods”, 19 December. www.newsdeeply.com. Available from: https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/womenandgirls/articles/2016/12/19/indian-comic-book-thats-taking-taboo-periods [Accessed: 25th February 2020].

Sen, Orijit (1994) River of Stories. New Delhi: Kalpavriksh.

Srampickal, Jacob S.J. (2006) “Development and Participatory Communication”, Communication Research Trends. 25(2). Available from: http://cscc.scu.edu/trends/v25/v25_2.pdf [Accessed: 22nd May 2010].

Walia, Nikhil (2012) “A Movement that Uses Comic Strips to Spread Social Awareness”. https://www.theweekendleader.com/Crusade/985/no-comic-stuff.html [Accessed: 25th March 2021].

[i] Plan India is a nationally registered organisation and a part of Plan International. Plan India was initiated in 1979 and has been working as a community development organisation, focusing on the child right issues. They are currently working in 11 states across India.

The non-government organisation (NGO) Adithi was registered in the year 1988 and aims at facilitating empowerment of women through economic and social development. Adithi stands for agriculture; dairying; industries (small-scale); tree plantation and tasar silk; handicrafts, handlooms, horticulture; and integration of women in all these sectors. It is based in Bihar.

Adithi/Plan project is based on a child-centred community development approach and the project is a partnership between Adithi and Plan India working through partnership. Adithi/Plan project is a co-ordinated effort to improve the status of children in the community so that all kids can enjoy their rights of survival, education, and participation.

[ii] Personality development: For Adithi/Plan personality development programmes were equivalent to skill development programmes, the outcome of which was to express and become active participants in making decisions of their respective villages. The final outcome of the project was the initiate a Campaign planned and implemented by children where the medium was comics.

[iii] In OT exercise, the use of alphabets O and T are used to teach the basic facial expressions.