The Din of Silence: Reconstructing the Keezhvenmani Dalit Massacre

Nithila Kanagasabai

Abstract

This paper is an attempt to reconstruct the Keezhvenmani dalit massacre of 1968 by placing it in the larger socio-political scenario, giving it a ‘pre-history,’ scouring the various narratives of the incident and its aftermath, the emotions and movements it spurred, and finally how it lives on – constructed and shaped by memories. Keezhvenmani often finds mention in the discourse of dalit atrocities as one of the earliest and most violent crimes in post-independent India. But the passage of time, lack of proper documentation and multiplicity of narratives have buried the incident in mystery and uncertainty. The incident in which 44 people, mostly women and children, belonging to dalit agricultural families, were burnt alive by landlords and their henchmen is more than just a class clash. Politics, caste and class issues are so inextricably intertwined that it is impossible to know where one ends and another begins. But at its core, it is a gruesome reminder of the treatment that is meted out to the oppressed when they start demanding what is rightfully theirs.

Keywords: caste, class struggles, Dalit, higher wages, Keezhvenmani, Kilvenmani, massacre, tamil nadu

What is history? An echo of the past in the future; a reflex from the future on the past.

-Victor Hugo

The shooting at Paramakudi and Madurai on September 11, 2011, in which seven people died when police opened fire on dalits who had gathered to pay their respects to their leader Immanuel Sekaran, is only one among the long list of dalit atrocities in Tamil Nadu. Even as fact finding teams and judicial enquiries ascertain the facts of the incident, one cannot ignore the voices of human rights and dalit activists who allege government complacency, police torture and mishandling of the issue. Suspicion about the State’s anti-dalit psyche is deafeningly loud and so is the fear of the recurrence of widespread caste clashes witnessed by the state in the mid 1990s (Dorairaj, 2011). Paramakudi now joins the lexicon of anti-dalit atrocities in Tamil Nadu- Mudukalathur (1957)[1], Keezhvenmani (1968), Melavalavu (1997)[2], Paralipudur (2011)[3]. The list is endless.

Keezhvenmani, often finds mention in the discourse of dalit atrocities, as one of the earliest and most violent crimes in post- independence India (Teltumbde, 2008); but the passage of time, lack of proper documentation and multiplicity of narratives have buried the incident in mystery and uncertainty. My interest in the incident springs from my identity as a Tamil, tracing my roots to a town near Thanjavur district where the incident happened, and deeply discomfited due to my caste identity – belonging to a non-brahmin land owning caste that traditionally practiced untouchability against farm labourers. My family hails from Chidambaram, which lies hardly a hundred kilometers from Keezhvenmani, and yet nobody from my family was able to recollect details of this event**. This tells a lot about the obscurity of the event in collective memory.

This essay is an attempt to reconstruct the event, looking at it not in isolation but by placing it in the larger socio-political scenario, by giving it a ‘pre-history’ (Amin, 1995) as it were, by scouring the various narratives of the incident itself, the aftermath, and the emotions and movements it spurred among the people and finally how it lives on, constructed and shaped by memories.

Introduction

The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting

-Milan Kundera

Keezhvenmani, an obscure village in the Nagapattinam taluk of erstwhile Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, shot to significance when in 1968, 44 dalits were locked in a hut and burnt to death. The violence was a response to their demand for wage hike. Keezhvenmani marked a defining moment in the discourse of violence against dalits in post-independent India. But while history books chronicle Periyar’s Self Respect Movement in great detail and even the anti-Hindi movement finds mention, Keezhvenmani for most part is shrouded in silence. While the incident has been of immense significance to the Left politics of the area and to land reform movements like LAFTI, outside of the dalit imagination and academic interest, it has almost ceased to exist.

On the night of 25th December 1968, 44 people, mostly women and children, belonging to dalit agricultural families were burnt alive by landlords and their henchmen in Keezhvenmani (Sivaraman, 1973). But the Keezhvenmani incident is more than just a class clash. Politics, caste and class issues are so inextricably intertwined that it is impossible to know where one ends and another begins. But at its core, Keezhvenani is a gruesome reminder of the treatment that is meted out to the oppressed when they start demanding what is rightfully theirs. To assign the dead agency only as daily wage labourers who demanded an increase in wages would be both misleading and unjust.

Context

Labour is the father of material wealth, the earth is its mother.

– Sir William Petty

Land and labour were the sites upon which these contests – of caste and class – in Keezhvenmani were played out. In the 1960s, Thanjavur district, the rice bowl of Tamil Nadu, accounted for almost one third of the state’s paddy production. Large tracts of land belonged to temple trusts. These were leased out to prominent members of the society who would then become cultivating tenants and exercise control over these lands. A mere 4 per cent of the cultivating households held almost 26 per cent of the cultivated land under their control. Conversely, Thanjavur also had the highest proportion of landless labourers in the state – an appalling 41 per cent (Sivaraman, 1973). Most of them were dalits- untouchables, impure. Extreme poverty and abject pollution made these people the lowest in class and caste. All of these factors contributed to a long history of oppression in this region.

The dalits who tilled the fields were usually bonded labourers. When the Communist movement started gaining momentum in the region and the labourers started demanding their rights, the zamindari system was abolished and the Tanjore Pannaiyal Protection Act, 1952 (later repealed) and the Tamil Nadu Tenants Protection Act, 1955 were passed. The labourers though, did not really benefit from this, because they just went from being bonded labourers to being highly exploited daily wage labourers. In 1966, due to fall in agricultural produce and various other economic reasons, the price of paddy shot up, and this led to the dalit labourers demanding half a litre more of rice. This new found voice of the traditionally oppressed, caused much trepidation among the Mirasdars, the land owning class that quickly organised itself into a union called the Paddy Producers Association (PPA), to safeguard its own interests (Viswanathan, 2006).

When the Left Communist kisans started taking out protests, claiming wages above the mamool wages, the Association refused to comply and instead tried to arm-twist the landless labourers into withdrawing from the Communist parties and becoming a part of PPA. When the labourers resisted, the association brought in workers from outside for harvest. The local labourers tried to prevent the outsiders from working in the fields. Pakkirisamy Pillai, a labourer from outside the village, was killed in the ensuing clashes. Also in the month leading to the massacre itself, three agricultural workers and prominent members of the CPI (M) led Agricultural Workers Association were also ruthlessly killed (Sivaraman, 1973).

By November 1968, the fault lines began to deepen. In fact, according to the farmers in the village, in a PPA meeting held on 15 November 1968, the Mirasdars openly threatened Keezhvenmani with arson if the farmers didn’t comply. Following this, the Thanjavur District Secretary of the agricultural workers association wrote to the then Chief Minister C Annadurai, seeking protection. The letter was acknowledged in January, a week after the massacre (Krishnakumar, 2005). The letter was also published in Theekadhir, the political organ of the Communist Party of India Marxist Tamil Nadu wing – the only paper that covered the Keezhevnmani incident extensively.

According to eye witness accounts, on 25th December 1968, at around 10 p.m., the mirasdars and their henchmen came in police lorries and surrounded the cheri (hutments), cutting off all routes of escape. They shot at the labourers and their families who could only throw stones to protect themselves or flee from the spot. They also started burning the huts in the vicinity. Many of the women and children, and some old men, sought protection in a hut that was 8 ft x 9 ft. The hut was burnt down, and the people with it. Both the sessions court and the high court that later heard the case, held that those who committed the arson were not aware of the presence of people in that particular hut (Krishnakumar, 2005). But eye witness accounts by the survivors point to an altogether different truth.

“They speak of the heart rending cries heard far far away, of the bolted door, of the burning hut surrounded by bloodthirsty murderers with lethal weapons, of two children thrown out from the burning hut in the hope that they would survive, but thrown back into the fire by the arsonists, of six people who managed to come out of the burning hut, two of whom were caught, hacked to death and thrown into the fire, of the fire systematically stoked with hay and dry wood, of the leading lights of the PPA, who led the rioting, going straight to the police station and demanding protection against reprisals and getting it. They were arrested much later after the matter had got out of the hands of the local police” (Sivaraman, 1973).

But these descriptions came much later. This for instance, is an account from the article titled ‘The Gentlemen Killers of Kilvenmani’ that appeared in the Economic and Political Weekly after the accused in the case were acquitted by the Madras High Court. The reportage of the event, immediately after it happened, did not quite run on these lines.

The ‘Free’ Press

The Untouchables have no press.

– B R Ambedkar

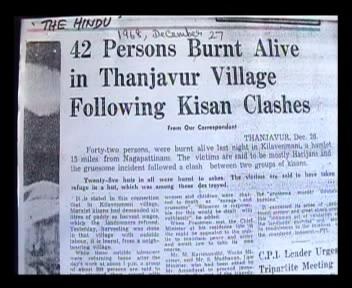

Most dailies – both Tamil and English – that covered the event saw it in isolation, shorn of its caste and class dimensions, and reported it as a conflict between two groups of farmers instead. The Hindu’s headline on December 27 read: “42 Persons burnt alive in Thanjavur Villlage following Kisan Clashes”1. Though the article goes on to mention that all the people burnt alive happened to be ‘harijans’ (a term used for dalits in that period); the event itself is not reported to have a caste basis. It is seen rather as a clash between two groups of peasants (1968). The Indian Express said, “Kisan Feud Turns Violent, 42 burnt alive in Thanjavur”2 (1968) Even Tamil newspaper Dinamani said, “Clashes between Kisans- 42 burnt alive” (1968).

The simplistic reporting masked caste identities and brought to the fore the media’s indifference to the dalit cause. When in 1973, the Economic and Political Weekly featured an article on the incident, post the Madras High Court ruling in the case, it scathingly attacked the media of the time for unquestioningly lapping up the state’s version of the incident. “The newspapers had informed us at that time that as labourers persisted in demanding wage increases year after year, the landowners exercised their ‘constitutional right’ to hire labour from wherever they liked. Outside labour was imported; local labour attacked outside labour; the poor fought the poor. What else could you expect from illiterate, uncultured labourers” (Sivaraman, 1973).

Anand Teltumbde commenting on the indifference of the media towards caste issues, argues that caste violence, even when viewed superficially, complicates reality. This is because it centres around the discourse of non-dalits attacking the dalits, and it becomes difficult for both the producer and the consumer of the news to then distance themselves from the story because they share the same value system that caused the violence in the first place. He also clarifies that even before the neoliberal reform, the media has had a dismal record vis-a-vis the dalits. This he reasons, is because dalits and adivasis who comprise one fourth of India’s population did not exist for the ‘nationalist’ media (Teltumbde, 2008).

The Judiciary’s Response

It is that privileged connotation which kneads the plurality of these utterances recorded from concerned individuals – from a mother, a sister and a neighbor – into a set of judicial evidence, and allows thereby, the stentorian voice of the state to subsume the humble peasant voices which speak here in sobs and whispers.

Ranajit Guha

Keezhvenmani massacre is an undeniable ugly truth, but it does not lend itself to clarity due to the various versions of the truth. The police for instance claimed that it came to know of the incident only the morning after, this, despite the fact that there was a police station barely three miles from Venmani. Discrepancies arise in the basic details of the case itself, like the number of people killed. While police records and post mortem reports fix the number at 42, the villagers and the union that took a census of the survivors the next day pin the number at 44 – 45 men, 20 women and 19 children (Krishnakumar, 2005).

Two court cases – Pakkirisamy’s murder case and the murder of 42 dalits – were held simultaneously at the Nagai Sessions court. The court ruled that while the former was not a planned attack; the latter was a preconceived and deliberate act. In the former, one of the accused was given a life sentence and the other seven were sentenced to rigorous imprisonment for varying number of years; in the latter, the accused were sentenced to 10 years rigorous imprisonment. Both the cases were taken to the Madras High Court. In the former case, the ruling was upheld; in the latter, it was quashed.

In 1973, the learned judges of the Madras High Court ruled thus,

“… there was something astonishing about the fact that all the 23 persons implicated in the case should be mirasdars. Most of them were rich men, owning vast extent of lands and Gopala Krishna Naidu possessed a car. However much they might have been eager to wreak vengeance on the kisans, it was difficult to believe that they would walk bodily to the scene and set fire to the houses, unaided by any of their servants. They were more likely to play safe, unlike desperate hungry labourers. One would rather expect that the mirasdars, keeping themselves in the background would, send their servants to commit the several offences which according to the prosecution the mirasdars personally committed… The evidence did not enable Their Lordships to identify and punish the guilty” (Sivaraman, 1973).

This was confirmed by the Supreme Court. In 1980, Gopalakrishna Naidu was waylaid by a group of people and hacked to death. The main accused in this case was a youth in his mid twenties called Nandan. Villagers say he was one of the eyewitnesses on that fateful winter night 12 years ago (Krishnakumar, Ramiahvin Kudisai (The Hut of Ramiah), 2005).

The Politics of it all

Oppression can only survive through silence

-Carmen De Montflores

When the HC verdict was passed there were no mass protests, no uprisings. Only a few hundred workers of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) marched to the High Court protesting the injustice. Even before the massacre, Theekadhir the political organ of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) Tamil Nadu was the only newspaper to document the brewing tensions in the region (Krishnakumar, 2005). Immediately post the massacre, the only people that reacted strongly were the Communists, under whose umbrella the kisans had protested. In 1968, when the incident occurred the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam was in power at the State. Just a year before that, they had won the state elections, becoming the first party other than the Indian National Congress to win state level elections with a clear majority on their own. Reacting to the carnage, the then Chief Minister C Annadurai, sent two of his ministers – PWD Minister M Karunanidhi and Law Minister Madhavan- to the site of the incident. He also conveyed his condolences and promised action (Clashes between Kisans- 42 burnt alive, 1968). But nothing much happened. In fact, Anna’s government was later accused of downplaying the incident (Krishnakumar, Ramiahvin Kudisai (The Hut of Ramiah), 2005).

When the Communist Party (Marxist) represented by MLA A Balasubramaniam sought an adjournment motion in the state assembly, regarding the Keezhvenmani incident, he said that it was a matter of emergency and great public importance. He also spelt out that the reason the party didn’t demand a judicial probe was to ensure that the offenders could be tried in a court of law and punished. The Deputy Speaker ruled out the adjournment (Venmani Incident, 1969).

Gopalakrishna Naidu, the president of the PPA, was known to be a supporter of the Congress (Venmani Incident, 1969). The DMK had completed just one year in its first tenure in power, in a country in which the Congress was not just the ruling party at the Centre, but also the only major pan Indian political party. That the DMK didn’t want to upset the power equations is more than plausible.

One of the most important features of DMK’s 1967 election manifesto was to provide 3 measures of rice for a rupee. Post the elections the new government was able to do only partial justice to this promise, by enabling sale of rice at a rupee a measure in Madras City (Chennai) and its suburbs, and in Coimbatore. According to the newly declared policy, the government was to procure the surplus produce of those holding more than 40 acres of land and distribute the same. But this policy was not strictly implemented. Furthermore, the ban on movement of rice within all districts except Thanjavur was lifted and free rice shops were given licences even in statutory ration areas. This meant that the DMK had to appease the powerful landlords for it to keep up its poll promises (Sivaraman, 1970).

Ironically, the DMK itself was founded as a breakaway faction of the Dravida Kazhagam popularly known as the Justice Party headed by Periyar, the pioneer of the Self Respect movement that sounded the clarion call for the annihilation of caste and religion. But while it encouraged the contravention of caste identities, it also facilitated the consolidation of non-Brahmin land owning castes. The irony is exacerbated when one notes that this caste-class dominance was precisely what the DMK, before it came to power, had accused the Congress of. Mythily Sivaraman, in her essay, notes how one of the couplets used widely by the DMK in its campaign is a lament of the widow of a DMK labourer who demands higher wages and is punished for the same.

My love, he asked for a tiny rise (sic.) in wages,

My love, he slumped dead with a bullet in his guts!

She points out that it is ironic that this was ‘enacted’ under the DMK rule (Sivaraman, 1970).

Teltumbde notes that since the 1960s, non-Brahmin castes have been responsible for most atrocities against dalits. These castes had emerged into a dominant position, becoming landowning peasant castes, and were then taking on the landless dalit labourers (Teltumbde, 2008). But these upwardly mobile backward castes also formed the major vote bank for the newly elected DMK government. The DMK’s sway over the Tamil public was tenuous and the times, tempestuous. The government chose to remain a mute spectator.

Following the massacre the DMK government appointed the Ganapathi Pillai Commission to look into the relation between the labourers and the landlords, and suggest remedies for the ‘existing tensions’. The landlords threatened to let 8 lakh acres of land lie fallow if the government failed to extend ‘protection’ to them. According to reports a large number of police personnel were sent to the field in the pretext of security, but clearly to prevent labourers from agitating further. Even when the report was released it recommended only a ten per cent increase in wages, which according to the Commission itself was measly and did not come near a ‘living wage’ (Sivaraman, 1970).

Keezhvenmani, forty years hence

Let the ruling classes tremble at a communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Workingmen of all countries, unite!

-Karl Marx

“The saga of struggles and steady political mobilization by the dalits in Nagapattinam district- despite setbacks such as the court rulings on the Keezhavenmani murders and periodical dilution of land ceiling laws in Tamil Nadu- stand out as a success story in the fight against exploitation and casteism in the country” (Forty years since Keezhavenmani, 2009).

On the 40th anniversary of the Keezhvenmani massacre, this is what an EPW editorial had to say. The flashpoint in 1968, became a shot in the arm for the political movement for higher wages. By the 70s, workers were earning much higher wages than before. This in turn was consolidated into a political movement, and the area remains a Left bastion till date. In fact, in the 2011 State Assembly elections the Kilvelur, the constituency that Keezhvenmani is part of, set a record with 91% voter turnout, the highest registered in an assembly constituency in Tamil Nadu (Satyanarayana, 2011). Land ownership patterns have also changed, thanks to the concerted efforts of the public, the state and NGOs. Many dalits who were previously landless labourers are now small farmers with land holdings.

Changing Lives

Personal transformation can and does have global effects. As we go, so goes the world, for the world is us. The revolution that will save the world is ultimately a personal one.

-Marianne Williamson

In an attempt to glean some counter narratives and understand the event from the perspective of those for whom it is a lived experience, I spoke to Krishnammal. For 85 year old Krishnammal Jeganathan, Keezhvenmani was a turning point in her life. She was around 200 km away from Keezhevnmani when the incident happened. She recounts the gory sight of violence that greeted her when she reached the place the next morning:

“I saw Ramaiyyah’s hut in which the people had taken refuge. Charred limbs of women and children were in a heap3. On a coconut tree near the hut, there were large blood stains. On enquiring, I found that one of the women had thrown a baby out of the hut, hoping to save it, but the men outside had butchered the child and threw the body back into the flames. I will never forget the horror of the event. At 85, it is the unfading memory of this event and the knowledge that the Dalits will remain oppressed till the time they are landless labourers, which inspires me to spend my life to empower rural poor through the redistribution of land” (Jeganathan, 2011).

Krishnammal and her husband Jeganathan shifted to Keezhvenmani post the massacre. Now forty three years later, they continue to live in the region. She initially started educating the children of the Dalits. But being born to landless dalit labourers, she knew only too well that the only way to ensure a better life for them would be to give them land. She recalls the barrage of opposition – from political parties, from landowners – she had to face in the initial years. Their organization, Land for Tillers Freedom (LAFTI) founded in 1981 has till date, she says, distributed 15,000 acres of land to 15,000 Dalit women. “I was not doing charity. When a woman eats her meal at the end of the day, it is not my charity. It is her hard work. I just facilitated that hard work. But I’m grateful to god I was at least able to do that.” Speaking about Keezhvenmani, she says,

“Now almost all dalit families there now own 2 to 3 acres of land. Most children belonging to these families have been educated and have found jobs in cities- in Mumbai, even in the Andamans. But if there’s one thing that disheartens me, it is the apathy of these very people who have suffered much injustice in the past. They have moved on, but they fail to see that many others have not. They think solely of their journey forward, breaking away from the shackles that once bound them. It doesn’t bother them that they are doing nothing to help those less privileged. The past seems forgotten.”

It’s not just the dalits who were subjects of change, Krishnammal continues –

“Many years after the massacre I got a call from Venugopala Naidu, a mirasdar, who initially opposed my initiatives to distribute temple land to Dalits. He wanted to meet me. I was surprised when he told me that he was bequeathing his vast tracts of land and his huge bunglow to the trust. He wanted me to use it for my work. The place is now called Jothi Illam and functions as a hostel for young boys who are being educated for free there.”

While interviewing Krishnammal, I bring up the topic of the HC verdict that acquitted all those accused, she brushes that aside, “What has happened, is in the past. A verdict cannot right those wrongs. Land reform can. Giving the dalits a chance at a livelihood can. That is what I want to do” (Jeganathan, 2011).

Krishnammal was not alone when she visited Keezhvenmani. She was accompanied by Mythily Sivaraman. Mythily was back in India after a four year stint in the United States of America during which she worked as a research assistant in the Committee on Decolonisation at the Permanent Mission to the United Nations. She was interested in the Sarvodaya ideals she met with Vinoba Bhave’s followers Krishnammala and Jegannathan. In fact, when Mythily and Krishnammal, accompanied by a CPI comrade, arrived at Keezhvenmani, the police suspected them of being ‘militants’. Mythily’s well-placed friends had to intervene for the women to be able to meet the villagers (Sivaraman, 2013).

The smell of smouldering ash and the howl of a dog looking for the family that had been there until the night before would continue to haunt Mythily throughout her life (Sivaraman, 2013). Her essays on the incident remain one of the very few documentations of the event in the English language and have been an invaluable resource for this research as well.

In the introduction of the book Haunted by Fire (2013), V Geetha and Kalpana Karunakaran write,

“That episode and visit brought home to Mythily the starkness of life in this grain rich part of Tamil Nadu… She realised that the price for dignity, for daring to declare oneself a communist was very high in these parts – many had paid with their lives… Unsurprisingly, in her subsequent reflections, she refused to concede that the monstrous incident at Kilvenmani was only a wage dispute gone wrong, and argued passionately for it to be recognised for what it was: class struggle in the countryside” (Geetha & Karunakaran, 2013).

It would not be off the mark to say that the incident and her experience of it laid the foundation of Mythily’s life-long mission of empowering the marginalised.

Fictionalising Fact

Truth is so hard to tell, it sometimes needs fiction to make it plausible.

– Francis Bacon

Popular culture – books and films – enables access to the larger ideological polemics and political concerns underpinning the society at a particular point in time. Two years post the Mardas High Court Verdict in the Keezhvenmani massacre case, in 1975, noted Tamil novelist Indira Parthasarathy, wrote Kuruthipunal (The River of Blood) that was a fictionalized account of the tragedy. It was serialized first in Kanaiyazhi, a literary magazine based in Delhi at that time. It was later published as a novel and won the author the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1977 (Viswanathan, Dalit struggle and a legend, 2003). He himself admitted that writing a story based on a real life tragedy was one of the most difficult exercises he undertook as an author. This he attributed to the fact that both the author and the audience knew the ‘real’ story. In Kuruthipunal, the assassin mirasdar employs a façade of machismo to hide his impotence. The CPI (M) condemned it as ‘a Marxist novel with a Freudian twist’ (Ramnarayan, 2010).

In the forty years since the event itself not more than a couple of mainstream movies have drawn from it. Among these, the most viewed is the 1983 film Kan Sivandhal, Man Sivakkum (which roughly translates to ‘The earth turns red, if the eye reddens’). Directed by Sreedhar Rajan, the movie tries to understand the power equations at play in a rural set up through the lens of a city based photographer journalist. The movie also employs koothu (dalit folk music and dance) to talk about the rampant oppression against the tillers of the land. In the movie, the agricultural labourers who demand for a wage hike are threatened and their houses are set on fire. The portrayal of media in KSMS is interesting. When one of the main characters Kaalai, a protesting agricultural labourer, dies in the process of fighting the landlords’ henchmen, the local newspaper reports that he was a Naxalite and died while manufacturing country bombs that the naxals were planning to use to attack the pannaiyar (landlord). This addresses the dubbing of Leftist agricultural protestors as Naxalites, by the State and the fourth estate thereby justifying the violence perpetrated against them by hegemonic powers, which has become a trope in every struggle against oppression (Rajan, 1983).

The movie Aravindhan (1997), takes off from the Keezhvenmani incident and dalits raising their voices against oppression. But soon, it digresses into a one man’s fight against the system. In fact the protagonist who is a college educated young man, turns to violence and guerilla warfare to change the system as it were (Nagarajan, 1997).

A comparative study of these two movies, lends itself to interesting observations. Both movies portray two characters that adopt different approaches to the problem of oppression. While one strongly believes that the fight against oppression can be won by peaceful means, the other is convinced that under the given situations, violence was the only option left for the suppressed. And surprisingly in both these movies, the latter dies while the former, in desperation, resorts to violence.

Ramiahvin Kudisai (Ramiah’s Hut 2005), is probably the only documentary based on the episode. The film weaves in interviews of dalit eyewitnesses who lost their kin in the massacre, retired local police officers and even a mirasdar who was initially convicted of the crime. One of the interviewees is Selvaraj, who recounts how he lost eleven of his family members to this horrendous crime. What makes the scene poignant is the fact that he does not break down like the others. There is an undefinable expression on his face which haunts the onlooker and conveys the fact that he is unable to come to terms with the incident even after 40 long years. Some survivors bear scars from gunshot wounds that have become perpetual reminders of their ill fate. These remnants of the massacre have been much projected and valourised by the CPI(M) members for lending impetus to their agitations4. But for the survivors and the relatives of the victims, the burden of this disaster has now become an indelible part of their lives and weighs down their hearts (Krishnakumar, 2005).

Speaking to Bharathi Krishnakumar, who made the documentary, gave a whole new perspective on how the massacre is perceived in the same place in this day and age. He talks about the irony in not having to face any opposition from political parties or the local police when he went to film his documentary 36 years after the massacre,

“Those in power don’t even perceive any threat from this incident. The memories are so vague and the people so powerless, that even raking up memory from four decades ago, they were sure, would not lead to any major agitation.”

Talking about the lack of this narrative in mainstream cinema he says,

“The untouchability continues. The victims of the massacre continue to be victims of untouchability even after their death. Mainstream cinema will draw from the terrorist attacks and other social issues that affect the ‘common man’… Even the LTTE question. But nobody is interested in the plight of the untouchables, a plight that has not changed much in more than half a century since independence. Art they say reflects life. It sure does, mass media practices untouchability as firmly as the society itself” (Krishnakumar, 2011).

He also believes that the incident has been shorn of political or social semantics, “Some people for whom Keezhvenmani is a lived experience, try to keep it alive through folk songs and laments. But for a whole generation that came after this massacre, it does not hold much importance. Large crowds gather at the monument every anniversary to pay their respects. But it has become more of a habit, a symbolic act more than anything. Even the grandchildren and children of those who lost their life in the massacre, remember it as some sort of a personal family history devoid of any political agency. This is mainly due to the fact that text books and media don’t give it the attention it deserves.”

Conclusion

It is often easy to become outraged by injustice half a world away than by oppression and discrimination half a block from home.

–Carl T Rowan

One of the most important questions I had to grapple with while working on this paper was that of collective memory and its exclusivity. According to the figures of the National Crime Bureau, every single day two dalit houses are burnt, three dalit women are raped, two dalits are murdered and eleven dalits are beaten. But compounding this fact, and make it even worse is the knowledge that only a miniscule percentage of crimes against dalits even gets registered. How does a collective memory deal with a human tragedy of this scale? What gets remembered, recorded for ever by posterity, commemorated, read and re-read? What gets forgotten, hidden in the crevices of our past? How does one make sense of the vast, varied instances of oppression?

Another issue I had to grapple with was the veritable absence of women in the narrative. According to village reports, of the 44 people murdered that night, 20 were women and 19, children; but surprisingly women seem missing throughout every commentary of the event. They merely feature as those acted upon. Never once, in all these narratives – political, economical, social, fictional and even subaltern – are they given agency. The ways in which women were affected by the movement, their struggles for survival and growth remain unexplored. They remain the sub-subaltern, relegated to the margins of even the subaltern. A critical historiography archiving women’s experiences can help in not just giving these unheard voices a platform but also invest them with legitimacy, enabling them to become if nothing, a site for textual struggle, an attempt at reclaiming history.

Remembering Keezhvenmani demands a reality check. It forces one to look at the long history of oppression against a group of people. But most importantly it compels one to think of silences, silences against oppression – big or small, extraordinary or quotidian, contiguous or distant, past or present.

Bio-note

Nithila Kanagasabai works on the issue of gender violence at the Prajnya Trust in Chennai. She completed her Masters in Media and Cultural Studies from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai in May 2013. She was a television journalist for two years between 2009 and 2011. Her interests include gender studies and cultural studies. She has co-directed two films – Badalte Nakshe (Changing Maps) that traverses the tenuous realm of children, memory and the 1992 Bombay riots; and Daane Daane Pe (On Every Grain…) that explores street-food politics in the city of Mumbai.

Appendix

1.

2.

3.

4.

Interviews

- Krishnammal Jeganathan, Female, 85, from Keezhvenmani- Founder of the Land for Tillers’ Freedom (LAFTI)

- Bharathi Krishnakumar- Male, 45, from Chennai- Documentary film maker, Director of Ramiahvin Kudusai.

- **P.R. Venugopal- Male, 85, from Chidambaram- Retired horticulturalist.

References

42 Persons burnt alive in Thanjavur Villlage following Kisan Clashes. (1968, December 27). The Hindu , p. 1.

Amin, S. (1995). Event, Metaphor, Memory- Chauri Chaura 1922-1992. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Clashes between Kisans- 42 burnt alive. (1968, December 27). Dinamani (Tamil) , p. 1.

Dorairaj, S. (2011, September 24). Targeting Dalits. Retrieved September 24, 2011, from Frontline: http://www.frontline.in/stories/20111007282012800.htm

Editorial. Forty years since Keezhavenmani. (2009, January 3). Economic and Political Weekly , pp. 6-7.

Geetha, V., & Karunakaran, K. (2013). Introduction. In M. Sivaraman, Haunted by Fire (pp. 7-53). New Delhi: LeftWord Books.

Kisan Feud Turns Violent, 42 burnt alive in Thanjavur. (1968, December 27). The Indian Express , p. 1.

Krishnakumar, B. (Director). (2005). Ramiahvin Kudisai (The Hut of Ramiah) [Motion Picture].

Nagarajan, T. (Director). (1997). Aravindhan [Motion Picture].

Rajan, S. (Director). (1983). Kan Sivandhal, Man Sivakkum [Motion Picture].

Ramnarayan, G. (2010, October 1). The Saturday Interview — The write stuff. Retrieved September 10, 2011, from The Hindu: http://www.thehindu.com/arts/books/article804496.ece

Sivaraman, M. (1970, January) “The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam: The Content of its Ideology” . The Radical Review, Vol.1, No. 2, 4-14.

Sivaraman, M. (1973). “Gentlemen Killers of Kilvenmani”. Economic and Political Weekly , 926-928.

Sivaraman, M. (2013). Haunted by Fire. New Delhi: LeftWord Books.

Satyanarayana, R. (2011, April 16). Kilvelur polls 91% votes, highest in TN. Retrieved September 5, 2011, from Times of India: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/Kilvelur-polls-91-votes-highest-in-TN/articleshow/7995148.cms

Teltumbde, A. (2008). Khairlanji- A Strange and Bitter Crop. Pondicherry: Navayana Publishing.

Venmani Incident. (1969, February 2). Theekadhir , p. 36.

Viswanathan, S. (2003, April 12). Dalit struggle and a legend. Retrieved September 20, 2011, from Frontline: http://www.frontlineonnet.com/fl2008/stories/20030425000607500.htm

Viswanathan, S. (2006, January 14). Keezhavenmani Revisited. Retrieved August 15, 2011, from Frontline: http://www.flonnet.com/fl2301/stories/20060127001608400.htm

[1]Also known as the 1957 Ramnad riots that witnessed clashes between the Thevars (dominant caste) and the Devendrars (dalits) after the murder of Immanuel Sekaran Devendrar.

[2]Six people were hacked to death. One of the victims was Murugesan a 35 year old Dalit, who had won the panchayat elections after Melavalavu was declared a reserved constituency in September 1996, but was unable to perform his duties as President because the Thevars physically prevented him from entering the panchayat office.

[3]More than two dozen houses and 10 motorcycles were set on fire following a clash between caste Hindu and Dalit groups.