The ‘Screen’ of Khandeshi Cinema

Shiva Thorat

Abstract

The screen can be understood as the metaphorical plane that in turn generates the physical plane through the ‘will’ of a subaltern collective. Onto the physical plane are projected the desires and differences of the collective. This can be argued in the case of Khandeshi cinema whose subaltern character lies in its struggle to constitute a ‘screen’. This struggle stretches from the political economy of its location, the status of the language it uses, to the history of its form. What began as a series of music videos in the Ahirani/Khandeshi has now attained self-awareness of its function as cinema. It can boast of the constitution of ‘Deewane’ interested in this cinema in spite of the perception that the cinema in question is unconventional. In spite of a territorial character, this phenomenon gathered enough attention in a decade that it has attracted the attention of the entertainment industry forcing it to respond to such an emergence. This paper based on textual analysis of prominent films and interviews of the people involved in this cinema, seeks to understand the process of the production of the ‘screen’ through the perceptions of its producers as well as its patrons while examining therein the equations of gender, class and caste.

Keywords : Cinema, Region, Khandesh, Maharashtra, Caste, Power Equation.

Introduction

Study of cinema traditionally concerns itself with ‘high’ cinema. This is similar to the obsession with culture as ‘high’ culture. In this era where most cinemas across the world have reached their high points in terms of extent, scale and reach; the newer and the emerging cinemas risk being ignored or at best seen as being ‘low’ in comparison to the ‘high’ cinema. This risk has also other facets. It is missing the opportunity for producing an understanding of the contexts of the emergence of this new cinema. Narendra Koli, a Khandeshi film maker and actor notes that “a cinema’s survival is ensured when it is in touch with the social realities and culture of a region or its people.”

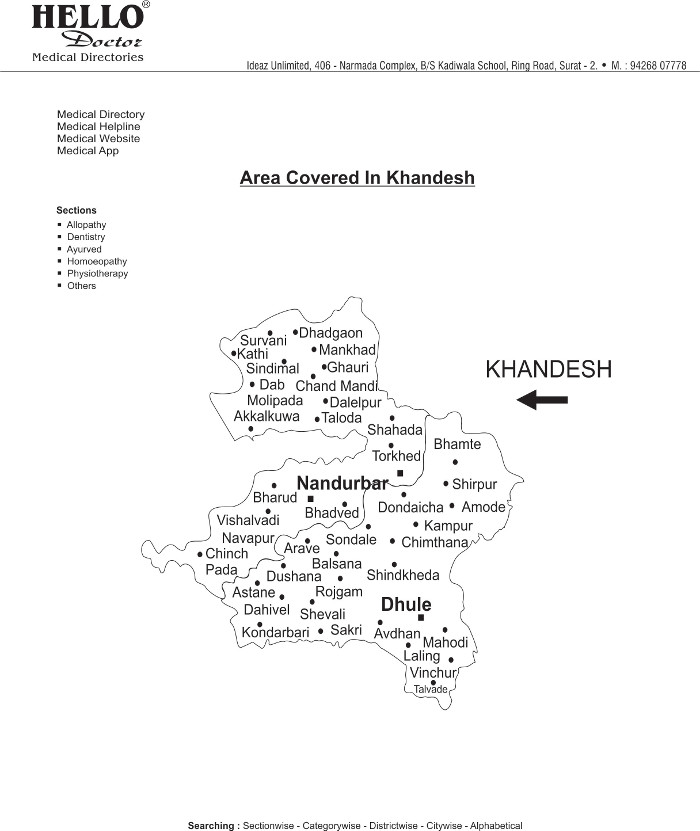

Khandesh is a region that is not easily defined by the geographic and administrative borders. The borders here are more at the level of culture in the form of the day to day experiences of the people. Khandeshi Cinema is produced within this region which is part of Maharashtra. References to this region are common in popular electronic and print media. Nandurbar, Dhule, Jalgaon and North Nashik with the prominent town of Malegaon and Burhanpur District of Madhya Pradesh constitute what is known as Khandesh. Among them Jalgaon, Dhule and Malegaon are the major places which produce films shot on video in Ahirani, Marathi and Hindi languages. The making of these films is also contributing to the production of the region.

(http://doctormyfriend.com/images/Khandesh.jpg)

There is also the use of the term ‘Mollywood’ or even ‘Mallywood’ referring to Malegaon which has shot into prominence. The video production in the form of music videos in the region emerged in the beginning of 1995. These music albums were about the day to day lives of people of Khandesh, reflecting on society and drawn from the oral history and the folk music of the region. This enterprise of music albums runs to date. It is not an exaggeration to say that because of this practice the people of this region experimented with producing content rather than merely consuming it. Enthused by the success of the music albums, this practice led to film-making. Among the themes addressed by these films are social issues such as superstition, honor killing and dowry system. The phenomenal growth of this cinema is attracting the mainstream production companies like Venus, T-series, Wings, and Ultra and TV channel.

Producing a ‘Screen’

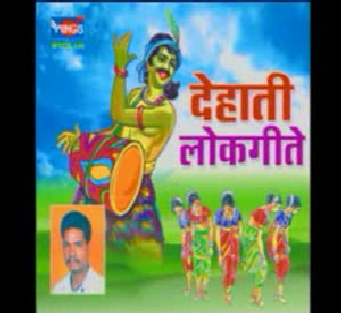

Khandeshi cinema addresses a particular region. The very first audio album of Khandeshi Cinema became famous and popular because of its connection with a public address.

(Source: Snapshot of one of the video song in ‘Dehati Lokgeete)

The name of the audio album was Dehati Lokgeete (Rustic Folksongs). This album was produced and directed by the Bapurav Mahajan. In his creation he tries to explain common Khandeshi peoples’ problems. The album appeals to a spectator’s experience about her/his day to day life. One of the songs of the ‘Dehati Lokgeete’ called ‘Dheere dheere gadi chalni…’ (Slowly the wagon goes…) talks of the livelihood stress in the region and the consequent migration. The singer addresses the village girl asking her if she would go to Bardoli[1]. The album was popular across the Khandesh region because the content was addressing the audience of that region. Pankaj More, a local, whom I interviewed, says that “It’s in Ahirani (language). That is the one and only quality I look for. Other thing is the faces of the actors that look like us”.[2]. The subjective experience of the audience is important here. The immediate appeal of the album was in its proximity to its audience.

Bapurav Mahajan said “As we had become popular due to Dehati Lokgeete we decided to make the videos. As we knew nothing about the video making, we made it with the help of a wedding videographer”[3]. In this album he tried to show the social economic situation of the society because of illiteracy, poverty and migration. Another producer, Ashok Mahajan, a school teacher based in Dondaicha which is a town in North Maharashtra, made movies which talk about the social problems in a comic way. The superstitions in society, the political parties with their failed promises, and problems of the disabled are the themes in his movies. He says that,

If we just tell people not to be superstitious, they may not listen to you. They do not want to listen to anyone speaking against divinity. That is their mentality. But in my experience through the movies people can be made to think. It is very effective.

A landmark moment in the history of this cinema was the release of ‘Kanbai na Navana Changbhala’ a reference to Kaanbai the deity for all of Khandesh in 2005. For the release of this film, a screen was ‘acquired’ quite literally by forcing the existing Hindi film to vacate. The early days of this cinema with its idealism has moved from music albums and ‘socially relevant’ cinema towards what appears to be an imitation of the Marathi and Bollywood movies. Each of these shifts is an attempt to constitute the screen. The first stage is fully dominated by the music album. Its success can be attributed to the urge of the people of Khandesh to see their own language and their culture on screen. The filmmakers’ focus on this aspect led to the constitution of the screen in the first place. Whoever decided to make the movie, wrote the dialogues of the movie and many times acted as the lead and other side roles. The need to see themselves and their culture on the screen and the fact that they are denied representation in the mainstream led to their attempts to overcome its dominance. With control over most facets of filmmaking they attempted a representation of the culture of the Khandeshi people.

In one newspaper interview, Nasir Sheikh the very well-known as film maker of ‘Malegaon Ka Superman’ says,[4]

What’s wrong if the Superman theme or Sholay, Shaan were copied by us? The issue we are showing in our film is related to our region only. In the big budget movies they talk about one particular family. But in our movies we talk about the North Maharashtra and also it’s very important to show our life because audience is only our people. No one else.

The International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in 2009 featured two films Yeh Hain Malegaon ka Superman and Gabbarbhai MBBS from this region, which got a lot of attention. The film Yeh Hain Malegaon ka Superman was a documentary on the phenomenon of filmmaking in Khadesh directed by filmmaker Faiza Ahmad Khan[5]. This film has led to a perception that the films are made only in Malegaon and the subsequent coverage by the very sympathetic media led to the coinage of terms like cinema from Malegaon or Mollywood. The Khandesh cinema screen might be inspirational for outsiders but it is made for those who want to see themselves on screen. Even Nasir Sheikh, the director of many remake movies of Malegaon, says that, “the movie which I produce and direct is about Malegaon. It might be similar to the characters of Ghazni, Gabbar and Superman but the issues show are local. The Malegaon people want to see themselves and the issues around them only.”[6]

I would like to problematize the ‘Supermen of Malegaon’ and read the multi-layered structure of Khandeshi Cinema culture which includes the intersections of caste, class and gender strata’s ‘intercourses and representations’. As Gayatri Spivak’s in her essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?” has powerfully confronted the representation concept of Gilles Deleuze. She was said, “Deleuze declares that there is no more representation, there is nothing but action”. Khandeshi Cinema is a production of collective mass who suffered their own day to day routines and found a way to consume their own ‘leisure’[7]. Producing the ‘Khandeshi Screen’ with suffering and leisure itself is an action.

(Source: http://rakeshsabharwal.files.wordpress.com/2009/12/graphic1.jpg )

The importance of understanding the cultural economy of Khandeshi people is not merely confined to financial transactions and profit making of culture industry but is closely tied to political articulations that emerge from this ‘underground’ economy. Khandeshi Cinema has no long history, but from the first album ‘Dehati Lokgeete’ they struggled for a ‘screen’. They are happy with the VCD-DVD’s, Video Corners and Memory Card distributions. The song ‘Mumbai Gayi Mi Dilli Gayi’ is one of the finest examples for saying that Khandeshi Cinema has reached every house of Khandesh. This song is a sort of an anthem of Khandesh. It catapulted Pushpa Thakur to the status of a matinee idol.

(Source: Poster of songs catapulted girl of Khandeshi Cinema, Pushpa Thakur)

While there are no actors who have achieved the status of stars, there are known faces. Due to the regular production there is a competition. This may be the reason why there are no stars. There is however an aspiration. Aaba Chaudhari says that, ‘language is motivation for making movies and albums’. Shubhangi Shinde looks up to Madhuri Dixit. The editor and film-maker Sukhdeo Mali says making money and showing his talent in front of people is the motivation to do this business. B Kumar Patil claims that, ‘cinema is finest resource to make change’ and for Bharat Saindane ‘acting and dance is life in his occupation.’ The challenges they felt in ordinary life is forgotten after someone reminds them that they are a star in Khandeshi Cinema. Kuldeep Bagul says that,

“I went to so many places to show my talent including Mumbai, Pune and Gujarat but no one recognized me, but with one negative role here, people think I am a real life villain. The great actor Nilu Phule had a similar experience. Children run on seeing me screaming ‘Paya wa may deepya una’ (Lady run! Deepya is coming)”.[8]

(Movie poster of ‘Vishwasghat’, sent by the actor Kuldeep Bagul by email)

Priyanka said that, ‘cinema is not only about the acting it is also about living life and feeling good about life.’ The success of Khandeshi cinema has attracted capital from other giants. The big budget movie from Khandesh ‘O Tuni Maay’ by Vinod Chavhan was funded by T-Series Company and was released in 2013. As with other films it was not screened in any theatre. Other than the stars, it had all the highlights in Khandeshi cinema until then. It failed to capture the audience although it has to be seen if it will get any of their interest.

(Source: Movie poster of ‘O Tuni Maay’, resource – Google Image)

In movies like ‘Dubrya No. 1’, ‘Dubrya Bhai MBBS’, ‘Lagey Raho Dubrya Bhai’, ‘Gadhadan Lagin’, ‘Man Dola Re Taal war’, ‘Natrangi Nar’ etc the themes and content are somehow drawn from the Hindi and Marathi movies but it’s relation with topic and characterization is only about Khandesh.

(Source: a snapshot from movie ‘Dhudkyabhai MBBS’)

For example ‘Lagey Raho Dubrya Bhai’ of the ‘Dubrya Series’ is about a dwarf and his struggle, but the structure of the story is drawn from ‘Lagey Raho Munnabhai’. In the Hindi film Sanjay Dutt, hero of the movie helps others to bring their happiness. In ‘Lagey Raho Dubrya Bhai’ the lead person who is a dwarf tries to solve problems which are local. Mainstream movies like ‘Munnabhai MBBS’ and ‘Lagey Raho Munnabhai’ might be an inspiration for Khandeshi Cinema but the issues and the content of the movies are about the people of Khandesh. The ‘Dubrya’ series, a collection of movies by Ashok Mahajan, tries to show the unlikely love story between one poor disabled person and the daughter of the feudal landlord from the village.

The Screen struggles

The film industry grew in proportion due to the working class patronage. This patronage is based on a demand for what has often been called entertainment or is based on a claim that the working class needs an outlet and that somehow entertainment makes them forget their exertion. Bhai Bhagat (2001) writes:

Human beings are always after knowledge and entertainment. They endeavour to attain knowledge. Entertainment is not different. They want entertainment to rejuvenate themselves. Singing, playing equipments and dancing are the major things for entertainment.

Apart from occupying the screen by force, films made in this region struggle to make it to theatre screens. They are however successful in selling the videos on CDs, DVDs, on local cable TV and now distributed as mobile phone videos which are loaded for a fee. To suggest that the people involved in making these films are making a profit is not the complete picture of this enterprise. That there is the earning of livelihood around it is the significant observation. But the practices of production are anything but mainstream. One of the major and prominent director-producer of ‘Khandeshi Cinema’ Aaba Chaudhari says that,

…Our resources are very limited and we work on a low budget. We cannot afford audition expenses. We select our actors randomly and start with the film making process since the story and the theme are already fixed… Our camera-men are very talented and have good understanding of the movie and shooting techniques. There are choreographers and music directors who are familiar with our culture. My job is to manage all these units and bring them together.

The almost tacky form of this does not distract the audience or patrons who appreciate this cinema because it is in their language and of their culture. The look and feel of this cinema has also been changing because of factors like competition and newer technology. But a significant theme I came across in my interviews is that the audience as patrons is given more importance than the ‘stars’ and prominent filmmakers.

Another insight obtained through these films is that there are several equations of power within this industry. According to Ashok Mahajan, a filmmaker, this cinema is only working for the marginalized people who never had other options of entertainment. But Bharat Saidane, a popular choreographer, actor of Khandeshi Cinema and winner of state level dance competition, maintains that:

Inside, the cinema is divided. Every industry is biased against the female worker. There are so many issues. Among them class and caste are prominent. Who the hell is going to stop these things? You are targeted if you speak up against these. So, no one takes up leadership to voice the concerns.

An interesting aspect is that a different sort of discrimination is practiced vis-a-vis gender. Most men who appear in non-prominent roles are not paid. The women are always paid. This points to a different interpretation of male camaraderie. Most men I spoke to claim that they worked for others out of ‘friendship’, never for money. Caste is also a prominent theme here. Most albums made in the name of Goddesses in Khandesh valorise the feudal upper castes. One of the actors, Bharat More says that,

It started from one of the early albums of Ahirani. ‘Amana Gaav Na Patil’ was an album made by an upper caste Patil and he only shows how Patil Community is prominent in every village. He gave chances to his relatives.

But it should also be noted that a good number of videos made depict Khandesh through the folk-songs which start as audio then video. These are liberal, address everyone and highlight problems and the issue of migration from Khandesh and are made by lower castes, especially from the Bhil and Scheduled Caste community.

The Malegaon reference was frozen when yesteryear actress Deepti Bhatnagar produced for one Indian television channel SAB TV a series called ‘Malegaon Ka Chintu’ which is about Chintu an innocent man who lives in a village of Khandesh.

(Source: Reality show in Television called ‘Malegaon Ka Chintu’)

The series is described in the following manner on the Youtube channel:

“… [the film] captures the eventful life of Chintu… a lively young man who lives in Malegaon and loves only three things in life; his coat, bicycle and Pinky, the most beautiful girl in town. He is full of life with a heart of gold. He is very emotional and cannot see anyone in trouble. The show takes the viewers through different situations in Chintu’s life that make for a laughter riot.”

The series is shot on location, in Malegaon. The actors Al Amin and Ashwini Khairnar are widely acclaimed to be from Malegaon. A claim is also made on the status of the Malegaon cinema and director Nasir Shaikh’s national and international fame.

In a certain sense this is to be seen as yet another constitution of the screen. Recently the team of ‘Malegaon Ka Chintu’ finished their second series called ‘Chintu Ban Gaya Gentleman’ which is a sort of a sequel to ‘Malegaon Ka Chintu’. In this Chintu is married and touring with his wife Pinky in India and abroad. The site claims that Chintu, “(b)eing a small town fellow, has reactions while exploring different countries/cities and culture. [These] are extraordinary and create lot of comical situations.” In a sense the channel has married the genre of destination TV content, popular on TV and a specialty of the producer Deepthi Bhatnagar to the supposedly immutable personality of Chintu – a small man from Malegaon. While the makers played on the newfound fame of Malegaon ka Superman, they make no effort to either utilize the idea of region or its language and instead draw merely on the name of Malegaon and produce humour through a series of gags. In more ways than one this is an act of silencing of the screen that emerged through the enterprise of the people of Khandesh. While the foray into mainstream television was through an act of silencing, the music video and feature films continue to flourish. There is now a sense among those associated with the cinema of this region that the time is ripe to increase the scale and extent of this cinema. One of the actors of Khandeshi Cinema Kuldeep Bagul said,

There is need to compete the mainstream cinema. They made audience addicted to a staple diet of love, drama and a scattered story which doesn’t have connection with the goings on in the society. And the continuation of these trope themes is unabated.

It also seems that the films that attempted to bend rules and stray away from tried and tested formula, have been doing well. Ravi Nikam, who is preparing for the UPSC and temporarily working in school as a teacher, says that:

We need to appreciate our language. The mainstream looks to us and appreciates our work. So we have to encourage our Khandesi filmmakers. Who else will sustain this?

Indeed the audience is the most important part of this phenomenon which ensures growth and sustainability. The enterprise is increasing in complexity and range. What were devotional and folk songs albums are now videos on all social issues. The case of Khandesi cinema brings back the question of patronage practices.

The entry of giant production houses is another prominent event which is making an ‘industry’ out of this enterprise. Companies like T-Series, Ultra, Wings, Krunal and Shemaroo have entered in Khandesh to make money. Recently a film made by T-Series ‘Malegaon mein Gadbad Ghotala’ was a success through distribution of CDs/DVDs of the film. The biggest budget so far for a film was more than 20 lakhs for ‘O Tuni Maay’ which was produced by T-series. This points to a possibility for this form of production to become a norm since it seems to be setting a standard; but this claim can threaten the existing media ecosystem. It is a threat for the characters of the screen constituted by the Khandesh films and is very different from the silver and golden screens of Film and Television respectively.

Conclusion

To conclude, I maintain that the approach to any culture as high or low is counterproductive. Creative processes and in this case social processes are to be seen as processes of resistance whose forms are dynamic. New production methodologies are possible because of technological developments and more interestingly how these are used in unexpected ways. What is assumed to be the default production mode is a hierarchical notion and needs to be more subjective. The conventional rule is to see movies on the screen in the theatre, but Khandesh Cinema has broken that condition and has challenged the notion of the screen. With the equations of caste, class and gender, the film-makers of Khandeshi Cinema come out with a good number of films and albums made with the help of their ‘friends’ and ‘celebrities’ and ‘patrons’.

Shiva Thorat has worked with digital media, and studied societal power equations and high-low culture. He was Creative Assistant for a media production company, and Dissemination Manager at the School of Media and Cultural Studies, TISS. As a Sarai Fellow, he worked on the invisible labour and the fugitive nature of small scale industry linked to “downloading culture” in Khandesh, Maharashtra. His publications include ‘Jugaad and Tactics, Reflections.’

References

Bhagat, B. 2001. Film Yatra. Mumbai: Lokwagmay Prakashan Gruh.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1992. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory, Dds. P. Williams and L. Chrisman. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dubryabhai MBBS, Directed by B Kumar Patil [Motion Picture] <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yE6eZcSeVj4>

Lagey Raho Dubryabhai, Directed by B Kumar Patil,[Motion Picture]<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUmp6F5t__E>

Malegaon Ka Chintu, Television Serial by Deepti Bhatnagar [Motion Picture] http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xebfai_malegaon-ka-chintu-6th-august-2010_shortfilms

[1]Bardoli in Gujarat is famous for the 1928 disobedience movement which produced ‘Sardar’ Vallabhbhai Patel’. It is also a centre of industrialization, and draws a large number of people from the Khadesh region.

[2]Pankaj More an audience and upcoming music composer in Khandesh gave an interview to me on 18th April 2013 in Thalner near Shirpur.

[3] As told to me by Aaba Chaudhary, a filmmaker in an interview.

[4]Malegaon Ka Superman, Maharashtra Times, Aug 19, 2011, translation by the author.

[5]The film Supermen of Malegaon was released as late as 2012.

[6]Malegaon Ka Superman, Editorial, Maharashtra Times, Aug 19, 2011.

[7]‘Leisure’ is concept used by the culture theorist Theodore Adorno to explain ‘Free Time’.

[8] Kuldeep Bagul, gives interview to the researcher in Surat on 6th April 2013.