Examining the Virtual Publics: The Case of Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy

Abstract

The digital platform has emerged to be a complex sphere of contestations. In the Indian context, the ubiquitous practice of building personality cults and the gathering of followers or bhakts allowed public figures to easily transition to the social media format to push their agendas. Self-professed gurus and government officials exploited the platform, generating click-bait posts that often displayed a total disregard for constitutional rights and fact-checking. Faced with an ever-increasing spread of misinformation, satire became one of the central ways for concerned citizens to express dissent. Several satirical narratives sprung up to expose the hegemonic narratives. These counter narratives fought the initial attempts to quell them through tactics of anonymity and subversion of the system and went on to become cult figures in their own right. The format of the digital media allowed for them to garner quick following and the digital sphere is now a battle ground between these contending narratives. In this context, the current paper attempts to understand the digital public sphere and the role of satire through the case of the Facebook fan-page called Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy. This case presents an interesting instance to study the nature of the public sphere allowed for by the format of social media.

Keywords: Social Media, Subversion, Digital Publics

Introduction

Social media sites have brought an unprecedented sense of connectivity and provided a shared public space for documenting each individual’s life events, crafting their social persona and sharing their opinions on current events. The techno-optimists posit that in providing avenues for personal expression, new media technologies are professed to increase political participation (Papacharissi 2002). Some of the optimism is well placed, as there has been an increasing influx of the non-mainstream content and availability of several alternative spaces to express one’s opinion. But several scholars (Boeder 2005; Dahlberg 2001; Deuze 2006) have cautioned against such a simplistic formulation. The virtual space is a contentious ground between several competing agendas and the emergent public sphere is also a product of the contending ideologies.

Social media’s democratizing potential was pegged on it being a broadcasting tool which allows anybody with a certain amount of technical and educational capability to have a voice. But a careful examination would expose the convolutions of such a claim. Like any other mainstream media, including digital media, those without access are rendered silent. There are also questions regarding the veracity and verifiability of the content generated. The lack of gate-keeping, however, also makes it prone to spreading misinformation and polarising the spread of content through the circulation of personal agendas. With the careful monitoring of content by the state and increasing control of the digital platforms by the corporate media houses, undermines this characteristic lack of gate-keeping.

An important aspect of the social media practices is the production of personality cults. The production of personality cults itself is not new, but it is important to examine how cults are produced in the new virtual sphere. With the ease of production of content and particularly the ease of dissemination, i.e. anybody with access to technology can now disseminate messages without any financial costs, the business of producing personality cults has grown manyfold. There are specific mechanisms of reaping benefits through the production of personality cults on digital media. A person with a considerable amount of following on social media is a commodity in demand; the benefits could be reaped in monetary terms through endorsing consumer products or in political terms by furthering one’s agenda and wielding power over the followers. The social media platforms that have become sites of contestations of different ideologies can be analysed using the Habermasian concept of the public sphere. Though the concept itself has been criticised by scholars like Nancy Fraser (1990) for its limited applicability, it remains a useful analytical tool.

This paper attempts to understand the nature of the discourse constituted by the social media sphere and the role of satire in countering the hegemonic narratives through the case of Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy Facebook page.

Digital Public Sphere:

Fraser (1990) defines the Habermasian public sphere as a discursive space in which citizens deliberate about their common affairs, a theatre in modern societies where political participation is enacted through the medium of talk. This theatre of deliberation in the post-modern society has shifted to the virtual space. Digital media and particularly social media provide a discursive space for a large community of people. While physical communities were linked, and sometimes limited by, geographical and cultural connections, the virtual sphere stretches these limitations. Deliberations range from practical themes to ideological ones. Fraser (1990) argues that the Habermasian conception of public sphere is utopian and bourgeois, and has several exclusions, gender being the most significant. The social media space is in principle egalitarian and provides an equal voice to all the users, but an important question to ask is: does having a voice ensure being heard? Jankowski and Van Selm (2000) point out that the virtual sphere much like the real one is dominated by the elites. They argue that it provides public space but does not constitute a public sphere. Papacharissi (2010) argues that virtual public sphere is by nature exclusionary to those who do not have access to it. Further having information does not ensure an enlightened public sphere. Fraser (1990:62) also notes that “the official public sphere is the prime institutional site for the construction of the consent that defines the new, hegemonic mode of domination”.

There is a growing body of research examining the digital public sphere. Robertson, Vatrapu and Medina (2010) examine the political discourse generated on Facebook during the US presidential election, they use the Habermasian concept of public sphere to understand the exercise of deliberative democracy. They analyse the Facebook posts based on the frequency of the posts by an individual and their commitment to the dialogue. Conover et al.(2011) analyse the political polarization on twitter during the U.S congressional midterm elections. They examine the interaction between the individuals sharing the same ideology and those with opposing ideologies. Halpern and Gibbs (2012) do a comparative analysis of Facebook and Youtube as platforms for political expression; they note that YouTube tends to score low on politeness due to deindividuation[1], whereas Facebook as a result of being connected to the individual identity begets higher politeness. Wojcieszak and Mutz (2009) examine online groups as spaces which hold potential to expose the individuals to different political views. Most of these studies use quantitative methods to understand the behaviour of social media users and, in turn, examine the nature of the political discourse that is generated. A large amount of research on social media has also studied its role inpolitical activism and the role of social media in the Arab Spring, which was dubbed the twitter revolution (Howard et al. 2011; Gerbaudo 2012; Khondker 2011; Bhuiyan 2011). Wolfsfeld, Segev and Sheafer (2013) locate the role of social media in the protests; they emphasise the importance of taking the local context in analysing the social media behaviour and argue that the social media acted to complement the on-the-ground political activity. Tufecki and Wilson (2012) examine the role of Facebook in disseminating the information of protests, sharing news and coordination of logistics of protest. Khamis, Gold and Vaughn (2012) argue that the role of social media in a particular movement has to be contextualised within the broader political and social structure of each country and note that each instance has unique complexities.

There is very little research that has looked at social media in the Indian context. This paper attempts to study the case of a particular social media page by integrating it with the prevailing socio-political context in India. It tries to examine the nature of the public sphere realised on social media through the study of specific case of the Facebook page of Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy Peter Dahlgreen(2005) conceptualizes the public sphere as set of communicative spaces that facilitate exchange of ideas and formation of political opinion. He argues that the three dimensions, namely the structural, the representational, and the interactional, are useful in analysing the public sphere. He defines the structural as that which relates to institutional features; media ownership, control, regulation, issues of financing etc. In the case of the Internet this refers to the ways in which digital spaces are configured, accessed, and used. The content generated by mass media and the questions of accuracy, fairness, pluralism, and agenda setting are included in the representational dimension. The citizens’ engagement with the media and how they make sense of it is considered in the interactional dimension. This helps us understand the kind of exchanges that take place between different individuals on these platforms. This framework has been used to analyse the discursive universe in the case of Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy Facebook page.

The case:

Dr. Subramanian Swamy is an economics professor and an ex-cabinet minister who has been a prominent spokesperson for the Hindutva ideology. His public statements get a lot of attention and he is considered to be an opinion leader, his Harvard degree contributing to his image as a public intellectual. He is also very active on Twitter and has a following of more than a million people, whom he refers to as his ‘Patriotic Tweeples’ (Twitter Peoples) or ‘PTs’. A global fan group called Shankhnaad, managed his Facebook page and with his consent, posted content based on the manipulation of facts and vilification of history. For example, in one twitter post he links Kashyapasa Gotra to Kashmiris (explained in detail later). In 2014, an anonymous self-proclaimed software professional parodied this page with another Facebook page called Subramaniam Swamy, with subtle name difference of Subramaniam instead of Subramanian. The intent of this page was to counter the propaganda of the fan managed page through satirical posts. Since this fake account used Dr. Swamy’s picture on its profile and closely parodied the style of the original Twitter posts and Shankhnaad’s Facebook posts, many ardent followers of the politician were hoodwinked into following the page and sharing its satirical content. When it was brought to his notice, Dr. Subramanian Swamy demanded that Facebook takedown the ‘fake’ page. Unable to distinguish between the fan page and the parody page, Facebook issued notices to both the pages to add ‘Unofficial’ to their profile names, as both of them did not belong to the real person. While the parody page obliged, the fan managed page didn’t and hence it was taken down. The case garnered considerable media attention and has also been subject of several internet jokes and memes. The parody page, now called Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy, continues to make satirical commentary on the statements of Dr. Subramanian Swamy and other Hindutva propagandists. Today, it is an active page with about 4,72,466 followers[2].

Digital media and the branded self:

Since the digital sphere doesn’t have gatekeepers, it is prone to attempts by individuals and organizations to use it as a propaganda machine. Building a following in the digital sphere is relatively easy and potentially doable by anyone. The principles of marketing and branding goods are now applied to people. Coupland (1996) argues that personal branding is hardly a new thing; it is as old as advertising. Individuals have benefitted from projecting themselves in the public sphere in several ways. One can see it as an extension of the celebrity from the culture industry to the larger society. Politics and cinema have always garnered mass following. While this was limited to a few film stars and some prominent politicians, social media has made it possible for ordinary people to acquire a large following.

Alison Hearn (2008) argues that the goal of the branded self is to produce profit. Here the self is seen as a commodity for sale in the labour market which must generate its own packaging, positioning and promotion (Hearn 2008). The branded self can be thought to produce surplus[3] which can either be monetary or in the form of public influence. Branding produces symbolic values which are used repeatedly to create a standardized image of the person. Social media becomes an ideal site for such a project and helps build one’s brand through short advertising messages (status on Facebook, 140 character tweets on twitter) and images (profile pictures). A personal brand is highly valued by the market. Different websites like Forbes.com, Zimbio.com, ranker.com, etc.release the list of most popular celebrities on social media from time to time, which serve as indicators of the market value of that individual brand. The value need not be in terms of financial returns but also could be in terms of social power.

The Twitter activity of Dr. Subramanian Swamy can be looked at as a part of an attempt to create a personal brand. Though his political career spans several decades, social media has amplified his popularity. A very active tweeter since 2009, Swamy has built up his social media persona as a public intellectual and a fearless proponent of Hindutva ideology (The Huffington Post, India 2015). He follows an acerbic style on twitter with a frequent use of portmanteau to refer to opponents. For example: ‘Sickulars’ for secular opponents to his Hindutva propaganda and ‘Aaptards’ to refer to supporters of the political party AAP etc. He also gives sarcastic nick names to his opponents. For example: Robber to refer to Robert Vadra, Shree 420 to refer to Arvind Kejriwal, etc. He has garnered about 3.72 million[4] followers on twitter and a lot of the terminology coined by him has been adopted by his followers.

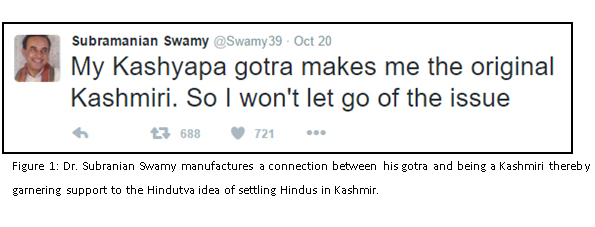

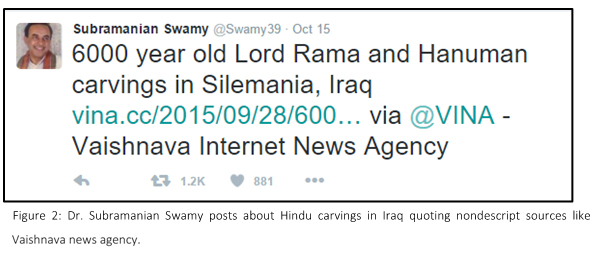

Figure 1 shows one of his tweets where he manufactures a connection between his gotra[5] and being a Kashmiri thereby garnering support for the Hindutva idea of settling Hindus in Kashmir.By this logic, his ‘gotra roots’ direct that he is the ‘original’ Kashmiri, so the occupation now gets justified as his right. The ultimate goal is to turn Hindus into a majority everywhere and quell the power of the minorities.Figure 2 shows his attempt to present ancient Hindu roots in Iran through some manufactured sources like Vaishnava news agency. Dr. Swamy repeatedly invokes the ideal of an ‘Akhand Bharat’ or an undivided nation of Hindus that will be established across the world. Through the use of his signature terminology his attempts can be seen as a way of promoting himself as a brand ambassador for Hindutva ideology on social media. The characteristics of his personal brand can be identified as unabashed proponent of Hindutva, who doesn’t present a garb of secularism (like ‘Sickulars’) and speaks for Hindu domination. These posts are aimed at making a social media spectacle and thus garner a large following that holds the potential to translate into greater political negotiation power.

The Facebook fan page of Dr. Swamy was managed by a Hindutva group called Shankhnaad which posted similar unsubstantiated content with the sole aim of propagating the Hindutva ideology.

Dr. Subramanian Swamy and the unofficial Subramaniam Swamy:

In the following paragraphs we will analyse the Shankhnaad fan page by adopting Dahlgreen’s (2005) framework that considers the structural, the representational and the interactional dimensions of the public sphere.

The structural dimension: As argued earlier,both the fan page and the fake page are hosted on Facebook and operate by the rules set by it.Facebookhas thecapacity to monitor and control the flow of communication on it. At the level of the individual pages, Dr. Swamy’s page is managed by a specialized agency which is adept at spin doctoring (the Shankhnaad.net page presents the team which works on different projects); Dr. Swamy himself being a well-known politician has the financial and political agency to have a voice in the social media space. The professionally managed page with considerable financial backing has the ability to employ techniques to garner views and followers.

The Representational dimension: The media output of the Shankhnaad fan page is the ideology of Hindu right and in terms of interaction, all the engagement is driven towards silencing any alternative opinions and to ‘market’ Hindutva to the digital citizens. This continual production of content to propagate the Hindutva ideology produces a hegemonic discourse on social media.

The interaction dimension: The Facebook page of Dr. Subramanian Swamy has a clear agenda to promote the Hindutva ideology and hence encourages interaction aimed at showing the supremacy of the Hindutva ideology; all comments and interactionsare aimed at furthering this agenda. The engagement is among like-minded Hindutva ideologues and there is little or no engagement with alternative views.

Here the platform of Facebook mustalso be discussed; the act of liking or following a particular ideological page on Facebook becomes the act of affirming one’s affiliation to a particular person or idea. By liking a page an individual is a) showing consent to receive information about the page b) pledging allegiance to the idea that the page represents c) announcing this allegiance to the world. Thus, an individual who likes Dr. Subramanian Swamy’s page would most probably have been a follower of his rhetoric or the proponent of the Hindutva ideology. As the act of ‘sociality’ in social media i.e., the act of announcing one’s ‘likes’ to the world is a public act, there is very little chance for people who do not agree to the Hindutva ideology to like or follow the page. There is also a possibility of individuals who want to counter the Hindutva discourse to like the page and counter the propaganda of the page. But this is very rare as the strength of the followers overpowers any possibility of alternative views. Thus, the format of the platform itself limits the kind of engagement that can happen on the people specific or idea specific pages.

To this hegemonic narrative, the Facebook page Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy can be seen as a counter narrative. Although Dr. Swamy has been active on Twitter since 2009, and the Shankhnaad fan page is operational since 2012, it was only in 2014 that the creator of the Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy Facebook page felt the need to present a satirical counter narrative to the dominant Hindutva campaign. In an interview to rediff.com, the anonymous person who created the page says,

Of late — from one year — I have been seeing Subramanian Swamy’s page — managed by Shankhnaad — with lots of misinformation against Christians, Muslims, Hindus.

And they try to prove it with Photoshopped pics. It was very disturbing seeing the educated lot sharing such info without thinking. That’s when this idea struck me. I also follow Swamy on Twitter, and was aware of his tweeting style. So I created this page to show funny things and claim everything belongs to our ancestors. I didn’t know it would click and grow so fast. (Rediff.com 2014)

Satire as counter hegemonic narrative:

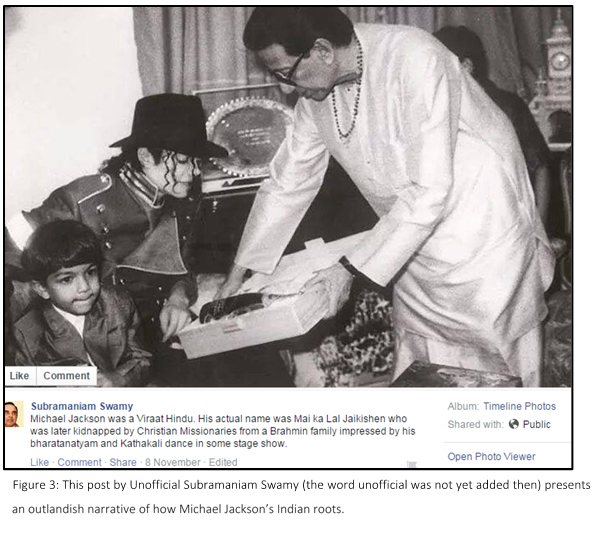

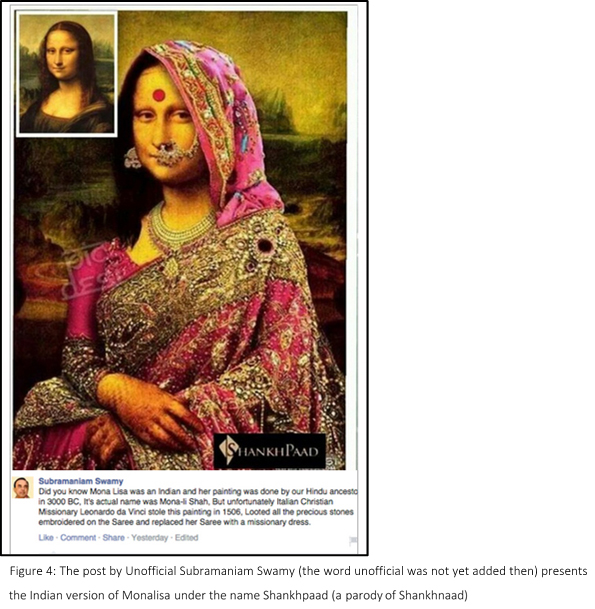

The Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy Facebook page began with a series of posts wherein international figures were claimed as having Indian roots. This content not only countered Dr. Swamy’s rhetoric but also gained a lot of media attention and followers (Figures 3 and 4). By ‘photoshopping’ original pictures and giving captions to old photographs out of context the page mimicked Dr. Swamy and his bhakt’s frequent distortion of historical facts to suit their own agenda. To add insult to injury, the posts also parodied Shankhnaad’s logo and called it ‘ShankhPaad’[6] instead. Counter narratives are particularly attractive tools for the out-group; they create bonds, shared understanding and social cohesion which subvert the master narrative providing alternative versions of reality (Delgado 1989). The outlandish narratives that ‘proved’ how Michael Jackson and Shakespeare were originally Hindu Brahmins brought to light similar bizarre ‘revised’ versions of Indian history concocted by Dr. Swamy and his ilk. In this way, the unofficial page’s satirical posts provided a counter narrative to Dr. Swamy’s own alternative narratives that traced everything to a fabricated Hindutva past.

Satire is the key element in the success of the Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy Facebook page. The centrality of satire is to be understood at two levels: in calling the bluff of the hegemonic narrative and to present a safe ground for the counter narrative. Jones and Thompson (2009:6) note that political satire has “the unique ability… to speak truth to power”. While Dr. Swamy uses his influence to propagate content that often shows a complete disregard for facts, the unofficial page parodies that same content to unmask his true motive. The genre of parody counters the hegemonic narrative using humour, which has two kinds of effects. The humour dethrones the high moral stance taken by the Hindutva hegemonic narratives and makes it look absurd; by doing so it brings it to the table for discussion. But the same humour also runs the risk of being considered cynical and hence not taken seriously. Boeder (2005) argues that the discourse on virtual public sphere loses its political character and takes on the flavour of entertainment.

Speaking in the context of the satirical news shows like The Colbert Report and The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, Jones and Baym (2010) point out that cynicism is not the modern notion of lack of commitment and detachment but a proactive protest against hypocrisy, corruption, insincerity, andextravagance. In fact, the act of producing satire itself proves that the creator believes it will make a difference in exposing the falsehoods that it is opposing. According to Peter Sloterdijk (cited in Jones and Baym 2010), satirists use their craft for their belief in truth. Without this conviction in the power of an equal debate, satirists would lack the motivation to continuously participate in the political discourse.

Satire also reconstitutes the binary of fake and real.Here, the page that was managed by the bhakts, the real fan page, was taken down as it was posting false unsupported content and the ‘fake’, i.e. the parody account, continues to exist by declaring itself fake, i.e. adding the word ‘unofficial’ to its title. In the context of ‘fake news’, Jones and Baym(2010) argue that the performances of the satirists is ‘real’ in the sense that they happen with a straight face, following public conventions, but there might be no truth in the performance; yet it is aimed at unearthing the falsehood behind the projected truth. The satirical performance deconstructs the public fakery and offers access to the real by the act of unmasking it. Jones and Baym(2010) employ Harry Frankfurt’s(Cited in Jones and Baym 2010) concept of Bullshit which is akin to Habermas’ idea of ‘strategic speech’, which is meant to manipulate the listener. Satire attempts to uncover the intentions behind this strategic speech to the people.

The satirical page posts content with slight distortion as posted by Dr. Swamy’s real page, in so doing it constantly pits itself against Dr. Swamy. It also presents quirky comments on contemporary events. The ambiguity between the real and fake not only aids the satire but also serves to maintain the anonymity of the person behind the satirical page.

The need for anonymity has to be understood in the context of the increasing judicial and extra-judicial control in the virtual sphere. The Aseem Trivedi case[7], the arrest of two girls in Mumbai for Facebook posts[8], arrests in Goa[9] and West Bengal[10] for satirical cartoons present instances of the state’s attempts to monitor and control digital content. The, recently struck down,Article 66A of the IT act 2008, could attract a maximum sentence of three years and a fine for sending offensive messages through a computer or communication device like mobile phone or a tablet.[11] The Indian government had asked Google and Facebook to pre-censor user content to remove inflammatory, disparaging and defamatory content in the past[12]. The proposal didn’t get through due to protests from the citizens and civil society organizations but there have been several attacks and arrests of people based on the content on social media. Social media has also been cited as reason for violence against minorities:A Hindu mob went on a rampage in the city of Pune in 2014 over some morphed images of Hindu gods, Shivaji and Bal Thackerey. A Muslim IT professional, who was in no way connected to this was attacked and killed by the mob[13].

These examples are only indicative of the growing intolerance even in the virtual sphere and the extension of the virtual sphere for wielding control over the citizens through the law and violence. In such an intolerant environment production of counter hegemonic narratives like that of Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy Facebook page is a courageous act.

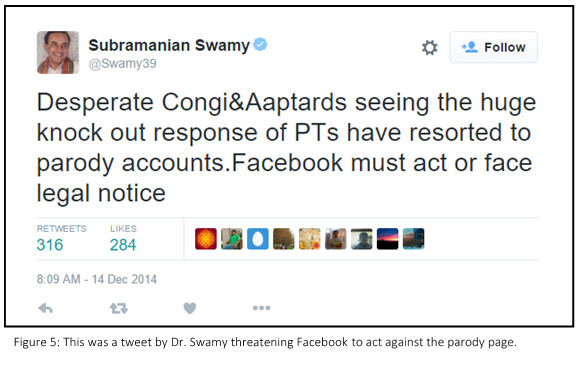

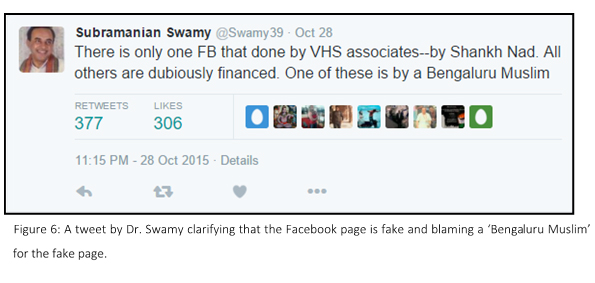

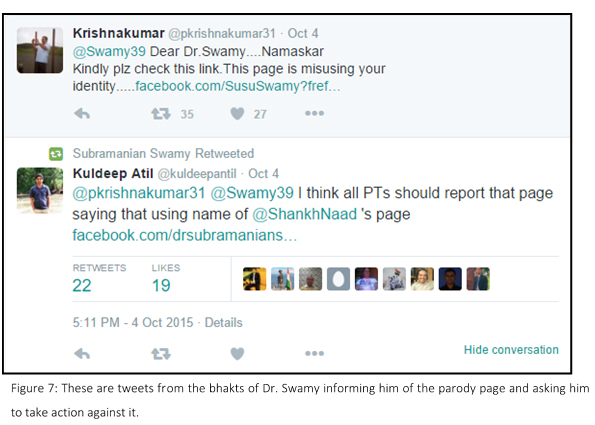

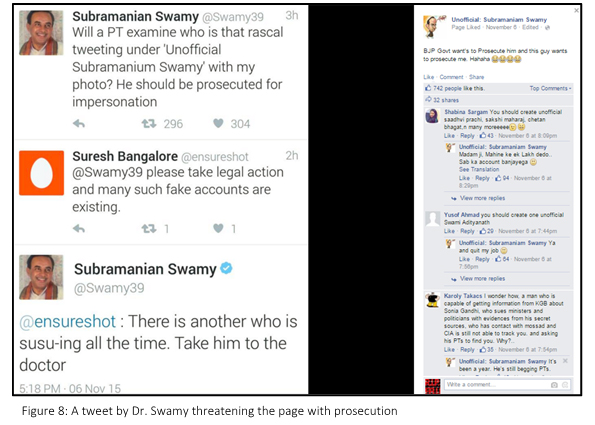

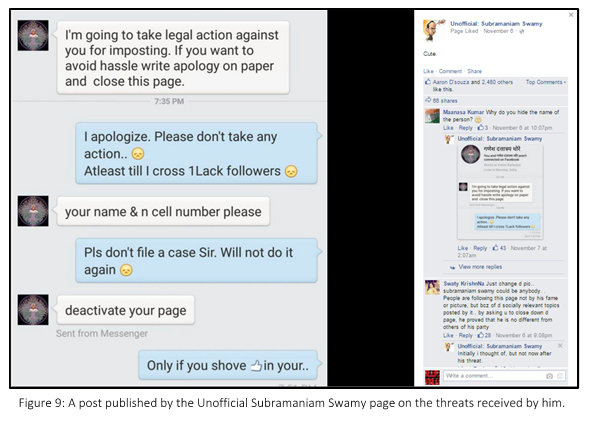

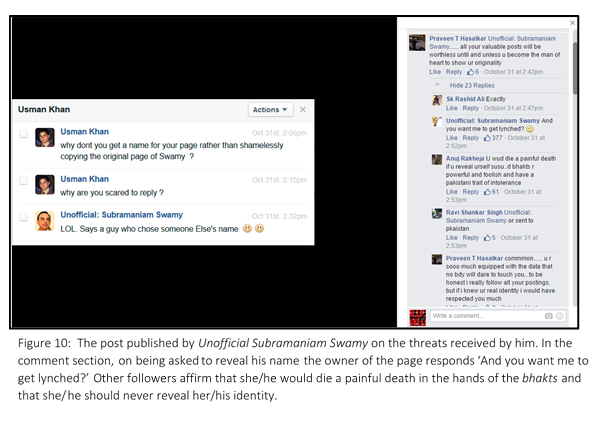

Dr. Subramanian Swamy had threatened Facebook with legal action if they did not shutdown the page(see Figure 5). There have been several instances of discussions on the need to shut down the Facebook page (see Figures 6, 7, 8 and 9). Interestingly the Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy page uses the threats received by him as posts to expose the Hindutva agenda. These threats are testimony to the close control exerted over the virtual sphere. In such an environment anonymity is not just a strategy of satire but a necessity. The act of satire is complete only when it evokes the expected response. Booth(cited in Gring-Pemble and Watson 2003) points out the necessary conditions for participation in irony; the individual has to first reject the literal meaning, next they should find out the alternative meanings and third the reader or listener must decide about the author’s knowledge or beliefs. The audience must determine whether the statement expects concurrence or reject it. There must be a tacit understanding among the producer of the satire and the audience for the satire to work. In the digital sphere, the success of satire can be gauged by its popularity; successful satire most often becomes a meme.

This intersection of anonymity, satire, and replicability through memes on the digital platform has interesting implications to the political communication done through the Facebook pages. As argued earlier anonymity in case of unofficial Subramaniam Swamy is both a strategy and a necessity. It has implications for the perception of the content and the reception of the content. Anonymity allows for the counter narrative to have a wider reach as an idea rather than an idea originating from an identifiable person. While the branded self-accrues discernible benefits from the social media activity, the anonymity of the parody page by limiting the possibility of deriving profit from it makes it an honest counter narrative. It makes a statement that it does not intend to leverage the counter narrative for any individual gains but rather for the common good.

The second aspect to be examined is the conversion of the content into memes and the implications of this. Richard Dawkin (1976) draws an analogy between memes and genes to explain the spreading of rumours, melodies, catch-phrases, trends etc. As genes replicate certain physical characteristics, memes are used to explain the spreading of certain cultural information. An internet meme refers to content that has been widely shared over the internet in a short period of time. Memes are immediately ‘consumable’ packets of content whose realization is in quick engagement and sharing. Much of the counter hegemonic satire gets its audience through mass sharing and become memes.

What happens to the satirical counter narrative in memetic form is an important question in the unofficial Subramaniam Swamy page. In memetic form satire reaches a wide audience; but does the reach itself warrant the spread of counter narrative? This question calls for further examination of the audience of the page and their interaction on it.

Virtual Publics:

Stephen Coleman (2005) argues that digital media presents challenges to traditional ‘indirect’ forms of representation in democratic societies. Jones and Baym (2010) propose a performance model of citizenship, as contrasted with citizen as something to become here citizenship is a performance which is to be performed at numerous institutions and a variety of contexts. It is a not a passive category but an active process. They argue that satire (in this case TV shows) is an open text thatrequires participation, and that participation in the satire can be thought of as performing citizenship. Extending this argument to the social media sphere, can participation in satire in the virtual public sphere be considered as a new virtual citizenship? Does liking and sharing satirical counter hegemonic content itself count as ‘participation’?

Fernback and Thompson (cited in Boeder 2005) argue that the virtual space gives an illusion of participation, it serves a cathartic role and makes the public ‘feel’ involved rather than actually being involved. Memes, while easy to share, are often not taken seriously, and due to the lack of accountability, remain fashionably political rather than trying to engage in any constructive counter narrative. Satire in memetic form increasingly serves merely as entertainment (Boeder, 2005). The research on the Arab spring (Gadi Wolfsfeld, Elad Segev and Tamir Sheafer 2013) has argued the importance of on-the-ground activity, along with social media, in the revolution; the social media activity in isolation slips into a cathartic activity and often only constitutes a cursory counter narrative which might not be taken seriously.

Rheingold (cited in Boeder 2005) emphasises on the commercial interests behind the technology. The platform of social media is a commercial structure and successful activity on it earns it millions in advertising revenue. The revenue itself is dependent on the number of followers garnered by the pages (both the hegemonic and counter hegemonic), so the apparatus of Facebook would consciously encourage these pages to increase their following i.e., would work towards making them cults. The interest of the for-profit social media sphere is in making a spectacle rather than creating a vibrant public sphere. The quickly consumable content that intends to constitute a counter narrative often only serves the interests and advertising revenues of social media companies.

Conclusion:

Through tracing the journey of the Facebook page Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy this paper has attempted to characterise the nature of the virtual public sphere and the role of satire in constituting a counter narrative to the hegemonic narrative. The conclusions can be characterised into production of the satirical counter narrative and engagement with the counter narrative in virtual sphere.

Production of the satirical counter narrative: In this particular case, the satirical page emerges with a clear intention to constitute a counter narrative to the hegemonic narrative. In the increasingly monitored digital space, satire emerges as a safe zone to be critical of the hegemonic narrative. The anonymity of the page, by not conforming to the accrual of profits, counters the branded self of the hegemonic narrative, which derives clear benefits from its ideology.

Engagement with the counter narrative in virtual sphere: The virtual public sphere on a private platform like Facebook which has specific mechanisms to derive profits encourages creation and spread of memetic content, which is quickly consumable. The counter narrative has to play by the rules set by the platform which limits the scope of the alternative it offers. The individuals engaging on these platforms often ‘consume’ and share the content as per the framework set by the platform. This highly individualistic participation performs a cathartic function and might not necessarily contribute towards strengthening the counter narrative itself.

Acknowledgements:

The tweets have been taken from Twitter handle of Dr. Subramanian Swamy and the Facebook posts have been taken from the page Unofficial Subramaniam Swamy.

Yamini Krishna is a research scholar at the English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad. Her research is on the history of urban development of Hyderabad around cinema. Her other research interests include popular culture, urban studies, Indian film and digital cultures.

Gauri Nori is a research scholar at the English and Foreign languages University, Hyderabad and has a Masters in Film and Literature from The University of York, U.K. She has over 5 years of teaching experience as part of the Liberal Arts department at the Annapurna International School of Film and Media. Her research interests include adaptation studies, aesthetics of film and experimental art.

References:

Bhuiyan, S.I.(2011)“Social media and its effectiveness in the political reform movement in Egypt”, Middle East Media Educator, 1(1):14-20.

Boeder, P. (2005) “Habermas” heritage: The future of the public sphere in the network society’. First Monday, 10(9).

Conover, M., Ratkiewicz, J., Francisco, M.R., Gonçalves, B., Menczer, F. and Flammini, A. (2011)“Political Polarization on Twitter”, ICWSM, 133:89-96.

Dahlberg, L. (2001)“The Internet and democratic discourse: Exploring the prospects of online deliberative forums extending the public sphere”, Information, Communication & Society, 4(4):615-633.

Dahlgren, P. (2005)“The Internet, public spheres, and political communication: Dispersion and deliberation”, Political communication, 22(2): 147-162.

Dawkin, R. (1976)The Selfish Gene. [add place of publication]:Oxford University Press.

Delgado, R. (1989)“Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative”, Michigan Law Review, 87(8): 2411-2441.

Deuze, M. (2006)“Participation, remediation, bricolage: Considering principal components of a digital culture”, The information society, 22(2): 63-75.

Fraser, N. (1990)“Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy”, Social text, (25/26):56-80.

Gerbaudo, P. (2012) Tweets and the streets: Social media and contemporary activism. [add place of publication]: Pluto Press.

Gray, J., Jones, J.P. and Thompson, E. (2009) Satire TV: Politics and comedy in the post-network era.New York and London: NYU Press.

Gring-Pemble, L. and Watson, M.S. (2003)“The rhetorical limits of satire: An analysis of James Finn Garner’s politically correct bedtime stories”, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 89(2): 132-153.

Halpern, D. and Gibbs, J. (2013)“Social media as a catalyst for online deliberation? Exploring the affordances of Facebook and YouTube for political expression”, Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3): 1159-1168.

Hearn, A. (2008)“12 Variations on the branded self”, The Media and Social Theory, 1: 194.

Howard, P.N., Duffy, A., Freelon, D., Hussain, M.M., Mari, W. and Maziad, M. (2011)“Opening closed regimes: what was the role of social media during the Arab Spring?”, Working Paper 2011.1., The Project on Information Technology and Political Islam (www.pITPI.org) at the University of Washington’s Department of Communication

Jankowski, N.W. and Van Selm, M. (2000)“Traditional news media online: An examination of added values” Communications, 25(1): 85-101.

Jones, J.P. and Baym, G. (2010)“A dialogue on satire news and the crisis of truth in postmodern political television”, Journal of Communication Inquiry,34(3): 278.

Khamis, S., Gold, P.B. and Vaughn, K. (2012)“Beyond Egypt’s “Facebook Revolution” and Syria’s “YouTube Uprising:” Comparing Political Contexts, Actors and Communication Strategies”, Arab Media & Society, 15: 1-30.

Khondker, H.H. (2011)“Role of the new media in the Arab Spring”, Globalizations, 8(5): 675-679.

Papacharissi, Z. (2002)“The virtual sphere: The internet as a public sphere”,New media & society, 4(1): 9-27.

Prasad, M Madhava (2013)Cine–Politics: Film Stars and Political Existence in South India. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan.

Rediff.com (2014, December 23). “Rediff.com:Troll of the year: The man who parodied Subramanian Swamy!”, Rediff.com India News.Available from: http://www.rediff.com/news/column/troll-of-the-year-the-man-who-parodied-subramanian-swamy/20141223.htm [Accessed: 5th November 2015]Robertson, S.P., Vatrapu, R.K. and Medina, R. (2010)“Off the wall political discourse: Facebook use in the 2008 US presidential election” Information Polity, 15(1, 2): 11-31.

The Huffington Post, India(2015, April 18). “Subramanian Swamy’s New Hindutva Outfit Is For English-Speaking, Social Media Savvy Indians”, Available from: http://www.huffingtonpost.in/2015/04/18/subramanian-swamy_n_7077126.html[Accessed: 5th November 2015]Stepanova, E. (2011)“The role of information communication technologies in the ‘arab spring’”, Ponars Eurasia, 15: 1-6.

Tufekci, Z. and Wilson, C. (2012)“Social media and the decision to participate in political protest: Observations from Tahrir Square”, Journal of Communication, 62(2): 363-379.

Wojcieszak, M.E. and Mutz, D.C. (2009)“Online groups and political discourse: Do online discussion spaces facilitate exposure to political disagreement?”, Journal of communication, 59(1): 40-56.

Wolfsfeld, G., Segev, E. and Sheafer, T. (2013)“Social media and the Arab Spring: Politics comes first”, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18(2): 115-137.

[1]Deindividuation theory argues that individual behaviour becomes socially deregulated in conditions of anonymity and group immersion, due to the reduction in self awareness (as cited in Halpern & Gibbs (2013:1160)

[2]From the time this paper was first presented in February 2016 to February 2017 the page has moved from 90,000 followers to about 4,72,000 followers.

[3]Speaking with regard to South Indian film stars, Madhav Prasad (2013) talks of two kinds of surplus amassed by a star; economic and political.

[4] This is the figure as on 11 February 2017

[5]Gotra is the clan name in Hindu religion.

[6] ‘Paad’ is slang for flatulence.

[7]Cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was arrested for his cartoons exposing the corruption of the political elite of India. See: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/sep/10/indian-cartoonist-jailed-sedition

[8]Two young women were arrested and detained by the police under section 505(2) on charges of promoting enmity, hatred or ill will between classes for questioning the shutdown of the city of Mumbai on death of Shiv Sena supremo Bal Thackerey. See:http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/2-mumbai-girls-in-jail-for-tweet-against-bal-thackeray/1/229846.html

[9]A small-scale industrialist from Pondicherry was arrested under Article 66A for posting status about the corruption of the then finance minister’s son

[10]A professor was arrested in West Bengal for posting cartoons about the chief minister on social media.

See:http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/West-Bengal-professor-neighbour-arrested-over-anti-Mamata-cartoons/articleshow/12650766.cms

[11]This act was struck-down by the Supreme Court in response of a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed by a law student Shreya Singhal. The Supreme Court opined that the section invaded that right to free speech and upset the balance between the right and the reasonable restrictions that could be imposed on such a right.

[12]The New York Times report on the Indian Government’s request for pre-censorship can be read at https://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/12/05/india-asks-google-facebook-others-to-screen-user-content/?_r=0

[13]See:http://www.firstpost.com/india/pune-muslim-techie-killed-by-rightwing-mob-over-morphed-fb-posts-1555709.html