The Limits of Jugaad:Innovating and Occupational Identity in Khandeshi Cinema

Shiva Thorat

Abstract

This paper is based on fieldwork in the Khandesh region in Maharashtra on the idea of cinema and its production practices, the occupational identities resulting thereof and the struggle for the development of a ‘screen’ for the practice of cinema. In this context, the process of constituting a screen is itself valuable, culturally empowering and an instance of Jugaad. Invoking Rai’s (2013) use of the term, I examine its relevance to the field in Khandesh Cinema. I argue that there is more to Jugaad than ‘solving and fixing a problem’. Within the framework of a historiography of Khandeshi cinema, problems have inspired innovative responses even as new ways to hack the system emerged. The problem in this case is caste and its attendant set of issues. In spite of the innovations brought to Khandeshi cinema by the ex-untouchable castes, the caste practices and the caste status of these communities persists, begging the question. The innovative potential of Jugaad and its social relevance given that the (power) structure and the social relations of the society are perpetuated by people’s occupations, is put to test. The innovators of Khandeshi cinema played important roles on and off screen. Dalit-Bahujans have been producing the ‘screen’ with the dint of their skills and innovations. That a Khandeshi cinema exists as an enterprise and a culture is due to them. Yet, their innovative and creative abilities have been negated. Ilaiah’s (2004) idea of ‘spiritual fascism’ rings true, with the elite occluding the power that the innovators produced for the cultural enterprise called Khandeshi Cinema.1

Key Words: Cinema, Politics, Regional Studies, Music, Identity, Occupation, Jugaad, Caste, Folksongs, Entertainment, Innovations.

Khandesh Region in State of Maharashtra

Any space to relocate its politics needs its historiography. The notion of region plays an important role in the construction of historiography of socio-cultural politics. In academic and administrative frameworks that have special interest to produce the history as well as documentation of land holding in the imagination of the Khandesh region, this paper examines the following.

As noted by Arvind Deshpande, in his book,

On 3rd June 1818, Bajirao surrendered …and the war came to an end …But in Northern most district of Maharashtra, namely in Khandesh, desolatory war continued for a fairly long time. Khandesh, lying between the main seat of Maratha Confederacy at Pune and the principal Confederates in North India, occupied a unique strategic importance. Bounded on the North as it was by the Satpuda ranges, it also was subject to depredations by such tribes as Bhils and Koli who infested this range. It was to Khandesh and through Khandesh, that followers of Bajirao would flock and try to escape into the North. Undoubtedly, Khandesh was an important charge, and Elphinstone recommended the name of Captain John Briggs of the Madras Army for this Collectorate (1987).

Deshpande would go further and talk more about Khandesh. A collector man named John Briggs had reported to Elphinstone. In a report Briggs states: “Desolation is everywhere apparent in Candeish (Khandesh). Immense tracts are covered with jungle, in some parts of which there still remain forts entire, and mosques appearing through woods, the monuments of better times” (ibid). The Maratha conflict which lasted from 1802 to end of 1803 were blamed along with the famine of 1804, unjust land revenue patterns of Bajirao II as well as the general destruction of life and property caused by the Bhils, Pindaris and Arab mercenaries. This gives a picture of the possible history which has shaped the understanding of Khandesh in the contemporary history of Maharashtra. This laid the foundations for the cultural practices among castes tribes and religious groups.

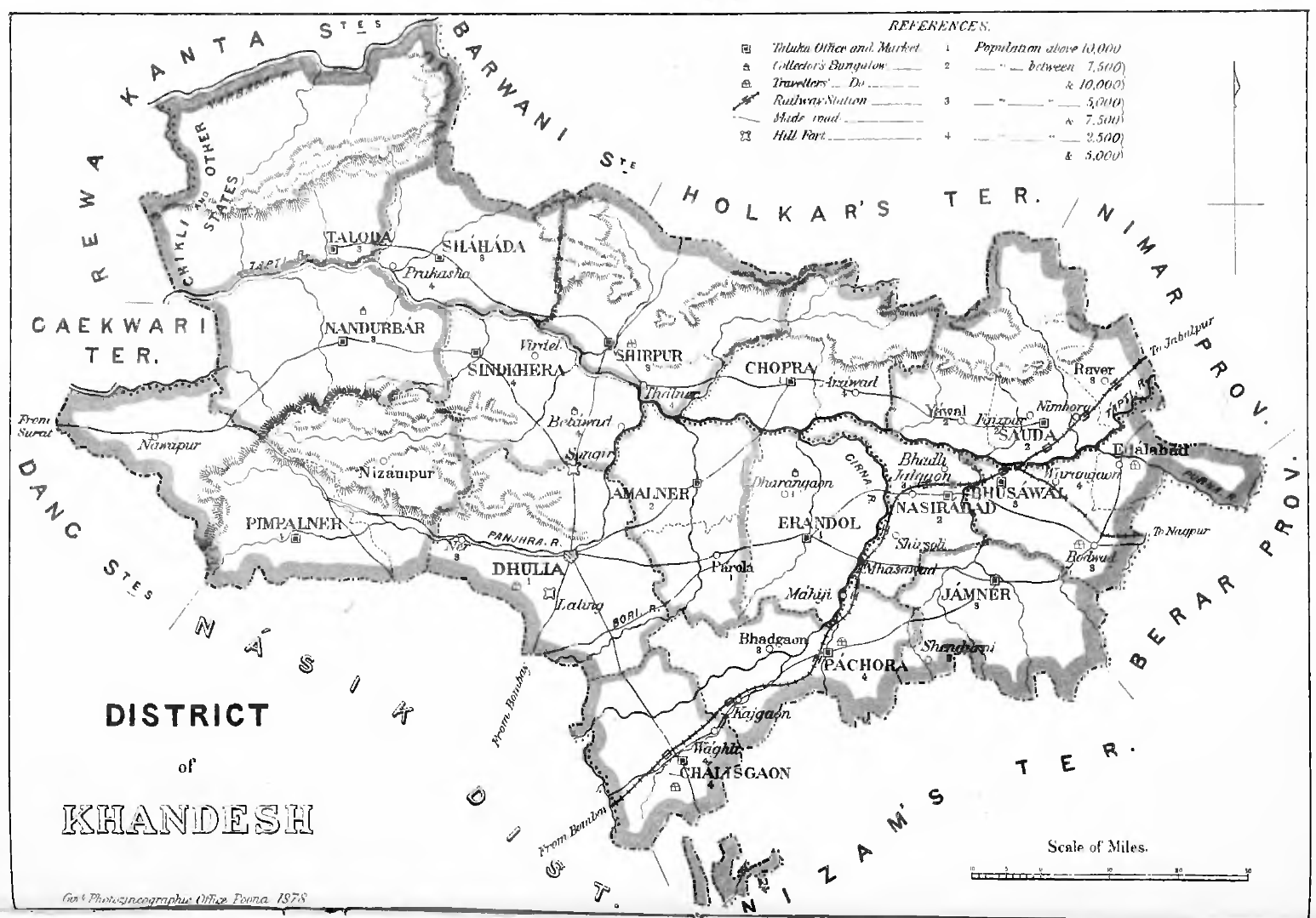

(Khandesh region in 1880, ‘Gazette of Mumbai Presidency – Khandesh’)

In 1880 the imperial government published a Gazette of the Bombay Presidency with a report on Khandesh and its exchange businesses. It exposed the relationships between the erstwhile Bombay Presidency and Khandesh. It explicitly shows that “Bhusaval railway and Bombay was the main bridge and the Agra highway was known to be the primary way of travel for the connection of Bombay and Khandesh. The chief connection of Khandesh to Bombay was the Narmada river which carried timber to the Bombay coast. Khandesh was one of the largest forests areas of Bombay presidency”.

References to this region occur in new ways like popular electronic and print media to describe the Khandesh region. The borders here are more at the level of culture, in the form of day to day experiences of the locals. Nandurbar, Dhule, Jalgaon and North Nashik with the prominent town of Malegaon, Burhanpur District of Madhya Pradesh constitute what is known as Khandesh today. Among them Jalgaon, Shirpur, Pachora, Nasik, Dhule and Malegaon are major places which produce ‘cinema’ in Khandesh.

Khandeshi Cinema

A brief clarification is in order. There is no cinema in the traditional sense of the term in Khandeshi cinema. Most of the texts are videos and even albums of songs. A thriving practice of making these ‘videos’ has resulted in what constitutes Khandeshi cinema. In that sense this repurposing of technology resembles what Crick (2005) in the context of political doctrines calls “attempt(s) to find particular and workable solutions.” Thorat notes that the origins of what came to be reckoned as Khandeshi Cinema began in 1995 with popular music videos which found favour with the locals. He says,

Enthused by the success of the music albums, this practice led to film-making. Among the themes addressed by these films are social issues such as superstition, honour killing and the dowry system. The phenomenal growth of this cinema has attracting the mainstream production companies like Venus, T-series, Wings, and Ultra and TV channels (Thorat 2015).

To investigate the geographic politics, cinema has proven its role and importance. Khandesh is a region of Maharashtra where the understanding of mainstream print and electronic media begins and ends with deprivation of the region. The image of Khandesh is not that of profound cinema consciousness but production and reproduction contributes to the visual familiarity of screen and reality. In specific understanding of cinema, Khandesh region would not call its industry a cinema industry. It is the audience who make Khandeshi Cinema Industry visible.

Thorat (2014) has connected the peculiarity of the differences among the castes and their choice of language. He says that while the upper castes prefer the use of Hindi and Marathi, it is the population of over 19 lakhs of notably, scheduled castes, tribes and Muslims who speak Ahirani and Pawari languages. It is the use of this language, he argues, that makes Khandeshi Cinema what it is. In the area of Malegaon, Hindi exists but with a mixture of Ahirani. Khandeshi Cinema’s use of these languages places it in an advantageous position to capture the issues and the imagination of the region. Thorat cites as an example the popularity of the song ‘Dheere Dheere Gadi Chalani Va, Baya Bardoli La’ (Slowly rolls the wagon to Bardoli) that highlights the poverty induced migration (ibid). In the absence of attention in the mainstream media, such media artefacts help fashion the understanding in the region. It is in this detailing of the issues that the videos reach out in the manner of cinema. But for the people who are involved with the production of Khandeshi films, it is by default that they bring out the complexities of their lives on screen. Despite many constraints such as affordability and being judged as a low culture industry, they have transgressed to constitute a screen culture. It is in this act of transgression that the politics of Khandeshi Cinema needs to be viewed. Positing the notion of Jugaad in Khandeshi cinema to interpret passable means and substituting technologies (video for film etc.) is to leave out the analysis of the true material conditions in which these ‘innovations’ take place.

But as is the nature of history, the attempts are invisibalised. The interface of the material world and the event is celebrated in the interpretations of affect and in turn repurposed in the service of the dominant, often capitalist formations. Khandeshi cinema received attention for its ‘frugal innovations’ (Rai, 2015) exemplified in the documentary ‘The Supermen of Malegaon’ and with it got drawn into the epistemological divisions of dominant cultures and little cultures, almost precluding any attention to the complexities of the event of its production. Of the various facets of this complexity, we look at caste and language for the sake of brevity. For phenomenon like Khandeshi cinema, the conditions for the oppression were preexisting in the form of caste practices. Nothing is more emblematic of this system of social organisation than the Marathi saying ‘Bamnya ghari livan, Kunbya ghari daan, Mahara-manga ghari gaan’. (To the Brahmin’s house belongs writing, in the peasant’s house the crops, and in the house of the Mahar and Matang (outcastes) performance of dance and music) This is essentially how the relations of production are organised typically on the screen in the mainstream. In the systematic hacking of technology, which is a crucial factor for the production of Khandeshi cinema, it is the lower castes and the untouchables that contribute to the essential labour and inputs and in the process, reproduces the caste system even while invisibalising the labour.

A useful example here would be the history behind the album Dehati Lokgeete (Rustic Folksongs) considered to be the first video made in Ahirani language. Most accounts identify the producer of the video to be Bapurav Mahajan (who belongs to the Kunbi community). But what gets invisibalised is the account provided by Ajit Ahire, whom I befriended on a social networking site (he identifies himself online as Ahirani Bhashik – Ahirani speaker). Ahire notes that it was Dhaka Ambore who is from ‘Matang’ community and a ‘Dhavandi’ (town-crier who beats the drum and declares notifications in the village) who composed and sang the songs that became the album. The music director of this video album owned a band that played at weddings and other occasions. A videographer who used to shoot weddings and events was the camera person and the editor for filmmaking. As these men were from lower castes, they chose to highlight the lives of the poor. It is not the first time that the productive contributions of Dalits-Bahujans have been overlooked.

Complications to construct the ‘screen’

But the journey to constituting the ‘screen’ for Khandeshi Cinema was not an easy one. It is an account that falls in the realm of innovations when seen from the perspective that frames Jugaad. It is an account of innovations in spite of the caste structures and also because of it. Enterprises like Khandeshi Cinema have its own social life. The complete involvement of all the sources of occupational identities has its significance which built the screen. There is an intricate connection between identities on and off screen. The definition of Jugaad provided by (Radjou, Prabhu and Ahuja, 2012) is ‘‘an innovative fix; an improvised solution born from ingenuity and cleverness.’’ They problematised Jugaad itself by saying “it carries a slightly negative connotation for some”. Rai invoking Clark’s (2008) idea of the ‘process of Ecological Assembly’ defines Jugaad as the, “…emergent machinic sensory-motor circuit of globalised digitality itself, in which any given obstacle in the way of a flow of desire through an ecology is pragmatically considered and worked around with whatever resources are to hand”(Rai, 2013). He goes on to note that it is “halfway between a representation” and what Bergson calls the idea of an ‘image’. It is this image that “has an ontological status in people’s perceptions, memories, and habituations….” Bergson says that “an image is half way between a thing and a representation. In other words, it is a sensory motor circuit” (1998 cited in Rai ibid). In this way, Jugaad is a sensory motor circuit of neural (brain) and spatial (material) plasticity (or potentiality).

The potentiality of ‘halfway of Jugaad’ in the context here is actuated by the oppression of the caste system. The social implications from many years now have all the facets of dignity and guilt. Priyanka Kamble, a Khandeshi Cinema actress, achieved nothing but abuses from elders, colleagues and friends for doing her job. Coming from a family that had the benefit of education, she was not encouraged to appear on screen or even dance. This was because her family viewed screen performance as a low caste occupation. Late Bharat More, who was an autorickshaw driver, had played the role of the brother of five sisters in a movie called ‘Satina Tak’ (The writ of the Goddess Sati, Aabha Chaudhari, undated). He recounted in 2013 that he always had to carry the shooting equipment as he was a driver.

Jugaad innovations in Khandeshi Cinema.

A Rai, A Sehgal and S Thorat argue that “the social practice of everyday hacking, digital and mobile workarounds, information piracy, illegal copying and sharing—in a word, jugaad culture— is an increasing feature of post-liberalisation India. But it has a history that must be understood as always involving repeatedly forgotten experiments in techno-perceptual assemblages”(2015). However, the social practices of India, dominated by the strict hierarchies of caste, maintained as social norms where, cinematic practices are also defined in alignment with caste hierarchies. Khandesh also practices the same hierarchies but the information piracy and workarounds of Khandeshi Cinema falls into the same category. Involved people of Khandeshi cinema can be found copying and sharing the jugaad culture. Sukhdeo Mali, videographer and editor, put into perspective his confrontation with Jugaad, He said that, “Do you remember the song ‘Mumbai Gayi Mi Dilli Gayi’ (I went to Mumbai and Delhi), there is a top angle shot. For that I had to climb onto the tree nearby. That song is so beautiful. You can see all dancers and Pushpa (Star and actress) in one frame.” Mali knew that he had to get the top angle. He had to make it happen. He makes use of something immediate, like a tree in this case.

Launch of new species that already know as product and industry structure such as the creation or destruction of a monopoly position and innovation is a process of industrial mutation, that incessantly revolutionises the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. (Schumpeter, 1976)

This power of creation however is unwaged in every sense of the term. Spivak notes that a “theory of change” includes the “substantial subversion of subalterns” (1988). In Khandeshi cinema the appearance of the narratives and the bodies of the low castes onto the screen, produces the twin effects of the ‘aura’ of low or little culture and underdevelopment. The understanding of the culture of production through notions of Jugaad is serving this subversion. Coming together of castes (Dalit-Bahujan in this case) may seem positive, but the connotations of the product of this association as impure or low is bothersome. Filmmaker, actor and singer Aaba Chaudhari2 said to me, “We are struggling a lot to make a movie. But we are making it. When I started making my first movie called Vishwas Ghat I didn’t think of I would be a filmmaker. I just share my feelings with my friends through a movie and my friends come with their own ideas to make it.” Aaba Chaudhari seems to take for granted the availability of talent that will serve well his idea of what ought to be a cultural product.

In this case, I find Rai’s (2012) argument on Jugaad appropriate when he is disputing with the book Jugaad Innovation regarding which resources create space for representations. Sukhdeo Mali is an example of using lived experience and technical talent to complete his desire of taking a top shot from above in limited resources and making that shot happen. His climbing a tree is a reference to the politics of his memories and perceptions. The instability of this screen is about their own day to day struggles which those people don’t claim as politics. Bharat Saindane3, a filmmaker, actor and choreographer said,

…when I started thinking of a music album called ‘Maale Mumbai tari Daav’ (Please show me Mumbai), I never had any kind of money and sources and neither an idea. Some friends came together and started to converse randomly; that was the moment we decided to make it. Everybody amongst us has had their own specialty with needful sources.

The film Yedasana Bajar (2007, The Market of Mad Peoples), was a collective and mass production from a place called Nardana in Dhule district. Many participants of the movie were from Nardana. My cousin Bhaiyya (also from Nardana) recounted,

Munna (comedian, filmmaker) from Nardana became famous in Khandesh due to his act as a comedian. People who saw him onscreen requested him to take them in his movie. His friend Kishore Shinde and he decided to make a movie and take only people from Nardana village. The local shopkeepers helped them create the location for the film Yedasana Bajar. The movie looked like a wedding video so he thanked everyone as in a wedding video.

The fascinating innovation of this film is that it begins with the idea of a wedding video and ends in the story of an innocent man who becomes rich after beating a local elite. The desire to become rich and also to be featured on screen by the residents of Nardana resulted in the innovations that made this film see the light of the day. Yedasna Bajar started with a parody song, Rup Tera Mastana in Ahirani. In the song, Munna addresses a buffalo, calling her his queen. It is a story of a village idiot. He day-dreams through the images of popular Hindi films. There is more to the film than what comes across. It is almost like the parable of David-Goliath, as he takes on the local factory owner, who is an exploiter of labour. He therefore avenges the crimes of exploitation by tricking him. The contributions of the village in the making of this film point towards their collective desires. They made it possible to produce the film in spite of the complete structural erasure in the realm of media. Their participation in the process of filmmaking makes a dent (small) in the monopolies enjoyed by the extant structures.

Jugaad Politics is peculiar in Khandeshi Cinema

Politics is politics, to be valued as itself, not because it is ‘like’ or ‘really is’ something else more respectable or peculiar. Politics is politics (Crick, 2005).

The Khandesh region is characterised by an economic culture that has seen monetisation recently. Their understanding of economics therefore is located in an almost barter like system. The fraternising of the communities is based on this notion of give and take. But we must note here that the feudal relations reproduced through caste also characterise economic relations. Some people are caste conscious about what is around them. Interactions play a major role to understand what has been happening with people. Eshwar Mali is a filmmaker and actor in Khandesh. He did a lot of audio-video albums in Khandeshi cinema. Among his albums Dhongi Dhongi Nach Mana Dajiba (My Grandfather dances bit by bit) is well known. He shows facets of realities to Khandeshi audience through the screen. For instance, he portrays domestic violence, introduces two dwarf identities and shows the differences between ‘High Culture’ and ‘Low Culture’. Now he is planning to make a movie on his own life, which has lot of ups and downs. He is a full-time vegetable vendor for survival in the village of Gorane. In his life he has interacted with all kinds of people, so he knows ‘society’s politics’. He writes even though he has no academic qualifications. Rapid changes were ushered since the days of the release of the album Dhongi Dhongi Nach Mana Dajiba and the entry of Pushpa Thakur in Khandeshi cinema. Here, innovations played a major role to develop individuals.

Burden of Caste and Dignity

The conviction of making cinema is seen as a duty in the world. There are thousands of people dedicated to making cinema. People leave everything from their life to make cinema, they are living making cinema their life. In the case of Khandeshi cinema, it is different. The world-famous director of Yeh Hai Malegaon Ka Superman Nassir Sheikh has his own business of wedding videos. Choreographer Bharat Saindane has his own Rikshaw to make ends meet. Aaba Chaudhari, filmmaker and actor works in a Seeds shop in Shirpur. Still, they have a key contribution towards Khandeshi cinema. Iliah says, “The rural productive masses in their day-to-day struggles evolved their own symbols around their production processes” (2004). There is a relationship between occupational identities and innovation of Khandeshi cinema. The investment of people’s locations and occupations is important in Khandeshi cinema but it does not have the dignity it should. The music director of the very famous album Kasa Karu Shingar (How do I adorn) has faced the problem of caste system’s various facets, therefore his various levels of innovations in Khandeshi cinema underlines the presence of caste. Dilip Bashinge4, shared his experience, saying,

One of my close friends was getting married and had contacted me to play and I joined the procession. I was happy because he was a friend. Interestingly, he and I had worked together for a video album. After marriage there was a dinner. One of his relative asked me to not sit with them, since it will be disrespectful to them if ‘Matang’ is seated with the upper castes in an event. I was not shocked when his relative told me this. But I was hurt when my friend remained silent.

A similar incident is shared by Bharat Saindane, who is also an aspirant filmmaker, actor and choreographer from Khandesh. He was treated disrespectfully even when he won an award in Pune. People never admired him and instead suggested him not to perform to his own songs again. Only because he belongs to Khandesh, people judged him on the basis of his location and occupation. Sukhdeo Mali, a videographer, is known for his diverse ideas. Once when he was on a shoot, he was asked for the perfect shot with limited equipment. He told them the perfect shot is not possible at all; he was abused by the director. Priyanka Kamble5, one of the actresses expresses,

I have been beaten by my father two times because I dance and my Atya (Paternal Aunt) has abused my mother many times. My family is well educated and has lawyers, teachers, doctors and some of them are in state services, so they want me to become like them.

Shubhangi Shinde6 also says,

My grandfather always abuses me because of my dancing in school and colleges. He doesn’t like my dance at all. I continued my dance as well as acting here. My grandfather stopped abusing me but only said one thing before he died that I became a ‘Lavani performer’ nothing else. Did you get it?

When she asked me this question, I did not have an answer. It is a collective question of those who are working and belong to the community of Dalit-Bahujan. In my understanding, ‘Lavani’ performance is as an innovation of the lower caste community to some extent. It was evolved for entertainment and then social mobility. After some time all the ‘Lavani’ performers were exploited by the feudal lords and the Brahmins. This resulted in modern restrictions that prove Khandeshi cinema is biased in different notions. Guru calls it “Untouchability in modern times is forced to hide itself behind certain modern meanings and identities” (2009).

These experiences are nothing but telling the truth of society. These abuses, taunts, beatings and cruelties by relatives, friends and urban colleagues are so fragile at one side but dark and construct the caste system progressively. The vision of Jotiba Phule (1827-1890) to unite non-brahmins and untouchables is difficult to see in society. Omvedt exemplified, “Phule sought to unite the shudras (non Brahmans) and ati-sudra (dalits), he argued that the latter were not only more oppressed but have been downgraded because of their earlier heroism in fighting Brahman domination” (2011). All these come from the understanding of ‘low culture’ which undoubtedly belongs to the Dalit-Bahujans. Ilaiah talks about confronting the locals which is even more important in the context of Khandeshi cinema:

In ancient times Sudras were made to kill Sudras and Chandalas were made to kill Chandalas, thus saving the upper castes the necessity of dirtying their hands. Injected with this ideology of cultural nationalism many Dalit-Bahuajans are now working in the ranks of Hindutva to kill their own Dalit-Bahujan brothers and sisters who have embraced religions like Islam and Christianity (2004: x-xix).

Innovations can be used to degrade, as mentioned above, an innovator. However, the Khandeshi screen is conflicting to the progressiveness and hypocrisy of upper castes. When the lower caste people’s sentiments came into focus, a lot of opposition was ready to disgrace it. There is no censor board in Khandeshi cinema but the social tension surrounding it, played the role of a censor board.

Attitudes and Politics

I remember listening to audio cassettes like Nachuyaat Taalvar (Dance on Rhythm) by Milind Mohite and Sham Sandhanshive. The music on these cassettes was devoid of lyrics. It was music with minimal instruments like Sambhal, Pipani and Dholki. Each played for around sixty minutes. Development of these songs gives dignity to mass development. When Nachuyaat Taalvar plays in ceremonies or events, people start dancing, especially women. It’s not that people have never danced before, but Khandeshi cinema gives them familiarity with the ‘digital world’ of cassettes. Dancing women collectively signifies dignity, which to some extent affects attitude also. At the time of Nachuyaat Taalvar, I have never come across nor heard of any digital form of musical instrumentation, but only the physical instruments.

There are a lot of upper-caste social phrases degrading ex-untouchables’ talent and culture in Khandesh. One of them is ‘kay mara-manga sarkha dhol piti rayna’ (why are you playing drums like the Mahars and Mangs). Casteist sentiments manifest in ‘functional culture’. It is a kind of invisible power and tends to degrade individuals and constructs occupational identities. Cinema propaganda has been, consciously or subconsciously, full of casteist attitude. It is a source to exploit the caste capital and make profit out of it. The connection of people engaged in Khandeshi cinema through their occupational identity is stronger on screen than in real life. The intellect of Khandeshi cinema and the produced films don’t have connection in larger politics of including the act of realism but the filmmakers also don’t believe in distributing their work freely to the masses, which comes from the priestly attitude of Brahmanism. Filmmakers primarily concentrate on profit, for sake of survival as filmmakers, but they have their own occupations. Peasants are peasants, cobbler does his/her chamari work, Kumbhar doing his/her pottery work. All are doing de-humanising work to survive. There is no difference in their socio-economical location.

Conclusion

In spite of having a connection to society with occupational identities, cinema has conservative norms with regard to caste and class practices. Innovations have helped to develop and progress Khandeshis to make films, but it’s also used to degrade them. Bharat Saindane calls this kind of practice as “maintaining the classification of caste system”. Priyanka Kamble, who worked as an actress in Khandeshi cinema expresses, “dance, the words and the life style of lower caste people is presumed as vulgarity by the upper-caste mindset”. Dalit-Bahujan’s creative and innovative abilities are negated. The barter system like India is constructed in a way where caste identities are the ones who are suffering a lot to survive itself.

The splendid work of Khandeshi filmmakers, stars and audience put their own recognition to each other’s development. An innovation of the knowledge and Jugaads are useful to construct, protect and preserve Khandeshi cinema but the burdens of caste system cannot help them upsurge from their own strata. Iliah gave the name of spiritual fascism which has roots from the past. He provokingly says,

The fault lies with us because the Indian socio-spiritual elite has kept the country under the grip of a spiritual fascism that hates social and spiritual equality and modernity. As a result, our innovative and creative abilities have been negated (2004).

It’s nothing but ‘Jugaad bhi ukhaad nahi paaya, jati imarat ka’ (Even Jugaad could not demolish the structures of caste.)

Shiva Thorat is an alumnus of the School of Media and Cultural Studies. He is currently a part of the production team in the CLIx project, initiated in collaboration between MIT and TISS and seeded by the Tata Trust. He has previously worked as a Sarai fellow, and as a creative assistant in various media production companies.

References

Adorno, T. (1991) The Culture Industry. New York: Routledge Classics.

Bergson, H. (1998) Matter and Memory. Trans. N.M. Paul W.S. Palmer. New York: Zone Books.

Clark, A. (2008) Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment Action and Cognitive Extension. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crick, B. (1962) In Defence of Politics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Deshpande, Arvind (1987) John Briggs in Maharashtra: A Study of District Administration under Early British Rule. Mittal Publications, Delhi.

Guru, G. (2009) Archeology of Untouchability. Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (37): 49-56.

Iliah, K. (2004) Buffalo Nationalism. Kolkata: Mandira Sen for SAMYA.

Navi Radjou, Jaideep Prabhu, Simone Ahuja. (2012) Jugaad Innovative. San Fransisco: Jossey Bass, A Wiley Imprint.

Omvedt, G. (2011) Understanding Caste. India: Orient Blackswan Private Limited.

Rai, A. S. (2015) The Affect of Jugaad: Frugal Innovation and Postcolonial Practice in India’s Mobile Phone Ecology. agepub.co.uk, 18.

Rai, A, Sehgal A and Thorat, S S. (2015) Jugaad and Tactics, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space.

Schumpeter, J. (1976) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. USA: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Thorat, S. (2015) “The ‘Screen’ of Khandeshi Cinema”. Subversion. 3(1): 1-12.

Thorat, S. (2014) Emerging Screen: Understanding the Cinema of Khandesh. Unpublished Master Thesis, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India.

Under Government Orders. (1880) The Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency- Khandesh. The Government Press.

[1] The author would like to thank assistant professor Nagesh Babu (SMCS, TISS) for his comments and suggestions. Author also thanks Rachna, Niranjana and Adwaita for the feedback provided.

[2] Aaba Chaudhari gave interview to the researcher in 2013.

[3] Bharat Saidane gave interview to the researcher in 2013.

[4] Dilip Bashinge gave interview to the researcher in 2013.

[5] Priyanka Kamble gave interview to the researcher in 2013.

[6] Shubhangi Shinde gave interview to the researcher in 2013.